How Tech Loses Out over at Companies, Countries and Continents

This article is part of a series on (European) innovation and capabilities.

Hi everyone,

This is a transcript of my presentation over at the European Microwave Week 2020, actually held in 2021. You can find the video here and the slides here. I’d like to thank Frank van Vliet, general chair of the EMW, for inviting me to do this talk.

The words have only been edited lightly - it is still presentation style, so here and there the sentences are not written like how they’d be in a more formal piece of work.

Transcript

Welcome everyone, to this perhaps somewhat strange presentation. I’ve been invited to talk to you about technology in the context of society. And that was my entire instruction.

So I decided to go wild and talk to you about one of the items that has been worrying me a lot lately. In this presentation, I’m assuming that you are all very technical people, or at least managing technical people.

I love technology. And I find microwaves to be fascinating, by the way. So it’s rather sad that I’m talking to you about something other than microwaves right now.

The theme of the presentation is how technology loses out in companies, countries and continents. It’s not a small thing. I’ll also talk about what we could do about it. Finally I offer a few links to interesting pages and books. You can find these linked from my website.

A little bit about me, why can I tell you about this technology stuff. I studied physics in Delft, although I dropped out. I launched a telecommunications company called PowerDNS, where I worked for 20 years. PowerDNS is the infrastructure for around half of the internet in the Netherlands and around one third in Europe.

And in the course of PowerDNS over the last 20 years, I’ve learned a few things. Meanwhile, I also did some work in national security contexts. I spent time doing DNA research at Delft University of Technology, and I have a satellite monitoring project. And these days, I’m also a government regulator.

So I’m a bit of a weird person with a broad range of interests. But I think these broad interests do enable me to do an interesting presentation for you on technological trends and innovation.

So for the past 20 years, I spent a lot of time within these telecommunication companies. These are basically all the largest telecommunication companies in Europe, and some in the US. And I’ve had many of these as my customer for either the whole 20 years or parts of the 20 years.

And over time, over the past 21 years even , I have seen these telecommunication companies develop. We all remember Bell Labs, and in the Netherlands, KPN Neherlab, when telecommunications companies were innovators, and they were the first to do many things, and when they did actual research.

And over the past 20 years, I’ve seen the extremely sad decline of all these communications companies into branding and financing bureaus, and this has impacted my own business, because I used to sell software, and now I sell services, because no one can buy my software anymore, because none of these telecommunications companies are technical companies anymore.

I spend a lot of time thinking about that, why? Why is that going on? And why is it bad? And that brings me to the central question of this presentation.

In any organization, in any company, in any group, any country and even any continent, what level of technical capability, do we need to retain? How technical do we need to stay to remain viable as a company or a country or a continent? And is there a point of no return?

If you outsource too much? Is there a point where you cannot go back and relearn how actually making things work?

So after this grand opening, we start with a very low tech example of innovation.

The toaster. Now, toasters are very interesting things. We rely on them to brown our toast. And they look simple but they’re also difficult things to make. We’ve all experienced terrible toasters that that burn your bread or the bread gets stuck in them, and how does it happen that people sell toasters this bad?

Let’s start with this overview of what is in a toaster. Here are the different components. We have the power plug, we have the fuses, we have a microcontroller, we have some source code, knobs, pieces of steel, and there’s the actual thing that browns the bread, and we have a temperature sensor and some coils.

If you are a toaster manufacturer, it is clear that you need to make some of these things in order to be a toaster manufacturer. But you don’t need to make all the things. So if we look on this next slide, we see we don’t we do not expect a toaster manufacturer to have their own iron mine or their own refineries or their own plastic factories or their own printing presses, or to have their own forests where they make paper or where they manufacture screws.

But is there a lot of other stuff that you can not do and be a good toaster company? In this presentation in this slide, we actually see a whole bunch of things that are sort of core to making a toaster, but maybe not.

So for example, the power cable, or the fuse, you could just buy fuses, you don’t need to make the fuses. So when, when Philips originally made their first toasters, I’m sure they also made fuses, because they were an all round electronics company at the time, but you don’t make a better toaster because you have a better fuse.

Similarly, the microcontroller, you can just buy it, you don’t need to build your own microcontroller to make a toaster. The coils you also don’t need, you don’t need to make your own coils. The power plug, there are people that make far better power plugs than you do. The temperature sensor, you don’t need to build a temperature sensor, you can just buy one, the knobs and the plastic bits on your machine, you can probably just order the knobs and the plastic bits from somewhere else.

And the steel, the components, you can just say, Hey, I’m not making these components anymore, I’m just asking someone else to make these steel frames for me. So you can also not do that. You can say, well, the firmware of the microcontroller, I also don’t need to make that I outsource that stuff.

And finally, what is left is the actual toasting element. And I found out, you can just buy these online in bulk. So you also don’t need to make those. And what is left as a toaster manufacturer is that you maintain the logo, you maintain the brand, you write the manuals, you do the logistics of shipping the toaster, and you’re going to be an actual credible toaster company without doing any of the things that are actually around making toast.

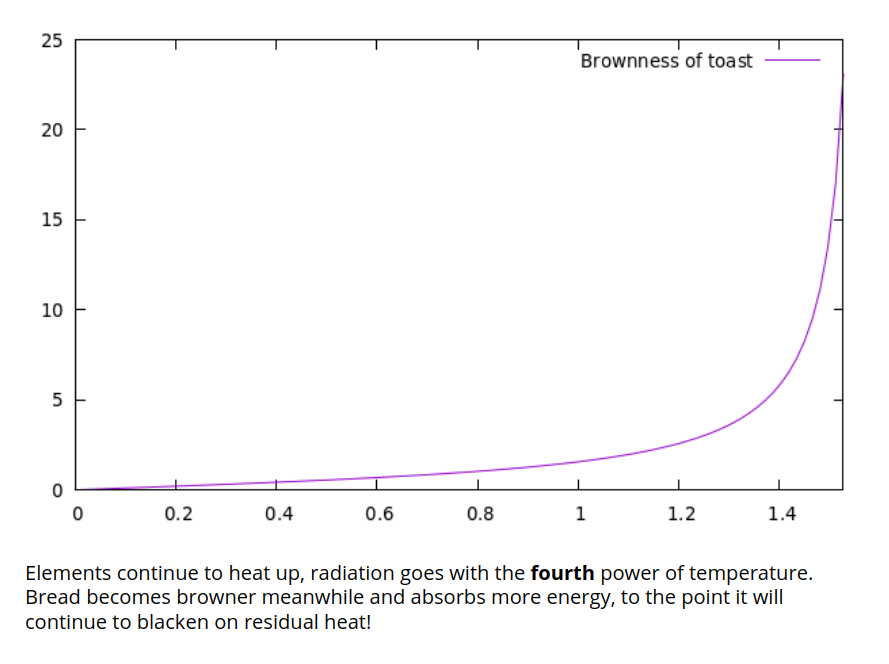

Now it turns out, and I have to put a graph in here, because it’s a technical conference, making a toaster is actually not that easy. There’s a fourth power law on how rapidly the toast will brown based on the temperature of the heating element. And as the bread turns browner, it also accepts more of the radiation.

So actually, there’s a runaway process where getting the bread toasted just right is a matter of seconds. So it’s actually not that easy to make a good toaster.

You can outsource all the things, you can just tell people look, we’re no longer making any of the components of the toaster, we’re buying them from the open markets. And then you need extremely strong quality assurance to make sure that you are not shipping a bad toaster.

Because you are no longer in control of all these elements, so suddenly, the composition of the metal might change and there is a coating on it. And that coating turns out to reflect infrared radiation. And suddenly it burns your toast. So you could be a good toaster manufacturer, outsource everything and then become extremely good at quality assurance.

And the question then is if you only own the logo, and write the manual and do the logistics, can you still innovate? Can you still be an innovative toaster manufacturer. And in theory, you could do that you could say, Well, look, we outsource everything. So we don’t build anything here anymore.

But we still have this room full of people that are experts at toasters. And we don’t allow them to make any toasters. They’re not allowed actually to do anything. But on paper, they are the biggest toaster experts.

And if they want to make anything, they will have to get other people to do it. Because we no longer have a lab. And because we don’t like these bread crumbs at our nice office. And the thing is, that doesn’t work.

If you are passionate about toast, you will not work at a company that does not build toasters, that only does marketing. So my central thesis here is that if as an organization, you outsource too much with the idea that we will still retain the designers and our own power to innovate, it will not actually work.

The smart people will not work for your company, because you have turned into a marketing and financing exercise. And the smart engineers, they want to build better toasters, they want to touch actual stuff. So the thing is, there is a point of no return.

If as a company you have outsourced too much. No good engineer will still want to work for your company.

UPDATE: Turns out someone did attempt to make a toaster from scratch! Staci Warden referred me to this TED talk by Thomas Thwaites “How I built a toaster - from scratch”. It is very educational.

Now, I could summarize my entire presentation with this awesome paper. This is a proprietary internal secret, Boeing paper and Boeing at some point, outsourced almost everything and they ran into trouble, they had this long before the 737 MAX. Boeing was already busy outsourcing everything. And when they built the 787 Dreamliner, they found that all they were doing was drawing designs and then handing them to manufacturers. They were even telling the manufacturers look, we only put up requirements, we don’t actually tell you what to do just build us this 787 Dreamliner.

And it didn’t work. And they nearly went bankrupt over it. And in the course of a lawsuit, this paper was filed. It’s online, you can read it. And in this an engineer, Dr. L.J Hart-Smith analyzed the process of outsourcing production.

And he came to the very wise insight that if you outsource production, it does not actually become any easier because the thing you are no longer doing now has to be done by someone else. And that can make sense under certain circumstances, but not under many others.

And you should really just read this PDF, everyone should read this PDF, it’s 16 pages, and it has graphs in it about the wisdom of firing all your smarts.

Basically, a key insight there is that when people say we are no longer going to build this ourselves, we’re going to have someone else build it for us, is that what is left of your company becomes ever smaller.

So as you do less, then the effort in doing something becomes relatively speaking far larger (and relatively more expensive), because your company has no expertise left in actually doing any things.

And this document clearly sets out when it is wise to partner with someone, and when it can be good for industry, and when it’s spectacularly bad for industry. And one sentence I want to highlight is that he says in the more general context, it should be obvious that a company cannot control its own destiny, if it creates less than 10% of the products itself.

And if you now go back to this slide with all these telecommunications companies on there, where I have worked for, they are all far down below that 10% level because they don’t do anything anymore.

So I spoke about a toaster company. And it’s of course very sad for the toaster industry of this world if they outsource everything and build mediocre toasters.

The problem is that this is not just a toaster problem. This is a continental problem. All over Europe, this is happening simultaneously, where we’re saying, look, we’re not that much into actually building things anymore.

So we’re just getting everyone else to build stuff for us. But don’t worry, we will hold the intellectual property. And the thing is, as much as you cannot make a toaster unless you have good people that are passionate about toast, you can not be an intellectual property continent and say, Look, we’re not building anything here. We’re just thinking about things and then telling some other people how to do their stuff.

In the end, you cannot survive if all you create is intellectual property.

So what have we outsourced? How bad is it? I made a sort of overview and it’s even worse than I thought. I know the telecommunication industry very well of course. And if you look within that world, they have outsourced the whole thing, and that includes the deployment of equipment. So the there’s actually no role for the telecommunication company there. They maybe will provide space for it. But also sometimes not that even, and the day to day maintenance, the system administration that has all outsourced, development, capacity building, administration, billing has all been outsourced.

So for example, invoicing, you’d think that sending out bills was core to telecommunications, but that also has been outsourced. So a typical telecommunications company, does not send equipment to its customers, does not design equipment, does not install equipment, does not maintain equipment does not send bills to its customers.

And you can wonder what do they do, and actually what they do is financing. But we’ll get to that later.

All our communications are gone - if you are sitting in an office anywhere you will be communicating with outlook.com, office 365, G Suite or Slack. We’re not running that. That’s all as a service, Microsoft and Google and Salesforce do that for us.

If we want to send a text message to you, well, if I sent an actual SMS message, then it’s managed by my telecommunication company, but they did outsource the management to somewhere else.

If we use WhatsApp or Telegram, iCloud, iMessage, or Skype that is all handled by other people, so we don’t run our own telecommunication infrastructure here in Europe. All our office enterprise software is not from here and being run as a service.

We barely develop any software here anymore. So even very European companies like like Nokia and Ericsson, that are now trying to tell us that they are building our European telecommunication infrastructure. They’re actually not, they’re getting that built by other people in other countries far away. Anything having to do with server and PC development and manufacturing, there’s nothing left of that in Europe anymore.

And by now, if you run your own servers, if because you say, hey, I want to have some control over what I do, even then people will tell you, you’re crazy, because you should give your service to Amazon or Azure, and they will run them for you.

So there is not a lot left that we do. Well, actually, there is something left.

Here in Europe, we do a lot of exciting financial constructs. So we have found ways that you can finance all kinds of things without paying taxes and, and driving up your stock price to tremendous heights.

And this, of course, is not anything real. If you move money around and you give it a different name, that doesn’t mean that you actually have made something.

We do a lot of intellectual property rights management here. We do marketing, we deal with customers for branding. But the main thing we do is we get actual experts in Asia, to design things for us and a manufacturer of them for us.

And then we sell those things here to our own European citizens. We do still do customer service here. But that’s mostly because our European languages are not spoken very well on other continents. Because otherwise, we would also have our customer service come from far away, and not even do that ourselves anymore.

Of course, there are exceptions, we still have some very exciting companies. And I know that many of you actually work for those exciting companies that are still building things, that are building satellites and microwave platforms and radar systems or pharmaceutical companies or agricultural companies.

And so it does still exist. But quite a lot of this work is actually intellectual property now, which means that you will be designing things on paper, and eventually someone else makes them.

So here’s a fun exercise. If you see a company that you talk to, and ask them what is it that you actually do? And they will say, Well, I’m a telecommunications company, I provide telephony and internet to consumers.

And you can ask on, what do you really do? And they will say, well, we operate the equipment, and we run networks, and we provide communications. And then you can ask, do you actually do that? Or did you outsource that?

And if you ask this question to almost all European telecommunications companies, they will say, No, no, we don’t actually run our own fiber networks or stuff or even our mobile networks, we have partners that do that.

And even if you then come to the parts that the company still does itself, for example, KPN in the Netherlands, they made a big move, they insourced their customer service again, they will start doing their own customer service again.

I was rather happy about that. And then I asked them, well, do you actually do that? And they said, No, no, no, we get all these people. They’re their contractors, they don’t actually work for us, we get them from a jobs agency.

And if you ask the questions to almost any company, except for the really high tech ones, you will find that most companies are now offices full, full of people, not actually making things, but they have other people that do that for them. And they’re mostly very far away. And even if these people are not very far away, you have to realize that if you have decided that as a company, that you’re only going to source things, realize that the company that is then building your stuff, they’re not going to innovate, they’re just going to build exactly what you asked for.

So this is a net negative for innovation. And I think it’s very important to stress that. This presentation is really not about hating on outsourcing, or people very far away. Because that can be very legitimate. The problem is about innovation.

If you separate the thinking about things from the doing of things, then innovation will suffer.

And we’re all technical people, we like innovation, we want to do new things. But where would it happen?

So how did that happen? How did we end up like this? And it turns out, there’s a very simple process, how we ended up here. If you start a new company, you always have to invent something, something has to be new, either there’s a technical innovation, or there’s a marketing innovation, but in any case, you started with something that wasn’t there before. So you start with an innovative mood.

And then you start hiring management, marketing and sales of course, because we as technical people, we are terrible, terrible at selling our stuff. I have a graph about that in the next slide, I think.

And then when the company grows, maybe in the marketing and sales, sometimes it goes wrong, you design a toaster for a market that doesn’t exist. And whatever, and then maybe you try again, hire new marketing people, but you can sort of without rebooting the whole company, you can do a new marketing campaign.

And then eventually your company that builds something technical, there is a failure, you have a new product, and it doesn’t arrive on time, or it arrives on time, but it’s not good, or, or it does not arrive on time. And it’s also not good.

And the reasons for that, well, you own them, you are the company, you try to build something, and it didn’t work. And that’s very expensive, because you might just have wasted like, like 500 person years of development work.

You’re not ever going to get that back. And it’s a failure. And very often, at that point, companies respond by saying, Well, apparently, we suck at making these these toaster components, we’re no longer going to make these toaster components, we’re just going to buy them on the open market.

And we have third parties that take on the risk of toaster development or whatever, but we are going to retain the profits, the money is still going to be ours, even though we don’t make this component of the toaster anymore.

This means that some technical people in your company no longer have a real job, they might still have a job on paper. But they’re not really making anything anymore, because their department, the thing they made is now getting bought somewhere else.

And some of these technical people I don’t know, give up. So they just lose interest, they’re no longer performing, they’re no longer innovating. They’re no longer happy. They’re no longer thinking about the product when they shower, because that’s where some of the best ideas come from.

And from now on, they’re no longer thinking about that stuff at home. And when the office they’re thinking about I want to be at home, or these people just leave the company. So after a failure, someone outsources stuff, says, Wait a minute, we’re just going to source that somewhere else, some of the best technical people now leave, which further increases the risk of future disappointments.

So some of your good people leave, that means that there is a higher chance that someone else, something else in the company will now disappoint and also be sourced from a third party. And if you go through this cycle a few times where you say, look, this is disappointing, we’re just going to buy this stuff from now on, you end up with a company that consists of a pile of contracts.

So the core of the company is no longer building something, the core of the company is buying something, and managing risk with contracts and procedures.

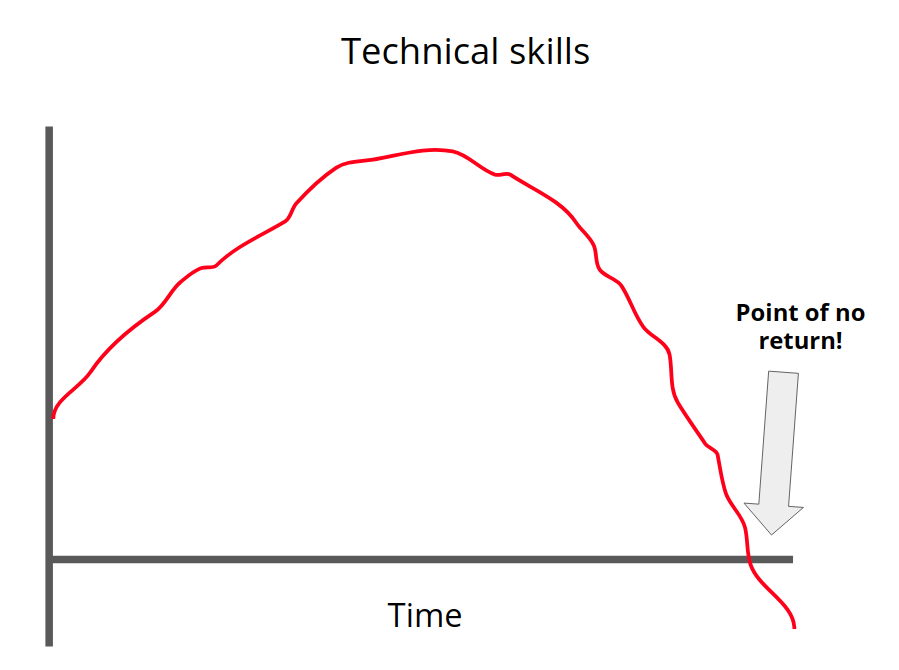

And this is a graph I promised, when you start a new company, initially, the innovative people, the technical people, they’re not really good at marketing things. So let’s say you invent a new kind of LED light. And the first thing all the technical people will do so yeah, it’s not really done. And it’s not reliable enough yet. And it’s not as small as I wanted it to be.

So initially, your technical people are actually negative marketing. They recommend that people do not use your product, because they know how it was built. And like yeah, don’t, don’t buy it. So initially, the marketing skills of a company are actually negative.

Over time, these skills always grow because good marketing is rewarded quickly. If you market your products, well, the growth comes quickly. This is unlike inventing a new microwave antenna because you spent like five years designing and building it. And maybe then you start making a profit.

But if you actually improve your marketing, the benefits are like real fast. So this is this is development that happens everywhere.

But there is a reverse development in the technical skills. At first, the company becomes better at what it does, the technical skills increase, and they go up. And eventually, the company turns more into a marketing place and the good technical people leave or they’re no longer enthusiastic.

And at some point, the technical skills of the company become negative. And what does that mean? That your company knows so little about what it does that if you would ask a random person on the street for advice on the thing that your company makes, they are more likely to provide correct answers than the people that actually work for the company.

And this, for example, can be seen in the 5G discussion, where if you ask someone working in a big telecommunications company what 5G is, they will tell you a whole story about self driving cars.

And it’s all bullshit. And the people on the outside they know that, look, maybe it’s a faster phone, I don’t know. But the people on the outside are not fooled that the 5G phone will actually improve your football skills, as actually one of the Dutch telecommunication companies is currently claiming.

So at some point, your technical contribution as a company becomes a negative and that’s the point of no return. Because then also no good technical person wants to work there anymore.

On shareholders, the people that care about the company, they should, in theory not be happy if you turn your company into this zombie pile of contracts that has no technical skills left. Turns out that shareholders are actually very happy with that. And how did that happen?

It’s mostly pension funds. And index trackers, if you look at who are the actual shareholders of big companies, they are all big pension funds, and they don’t really care. They want the company to make money this year, they want the company to make money next year.

Update: I’ve been informed that actually, this is not even what they want. They want the share price and dividend to go up, for now.

But in the longer term, they are not strategically interested in the company, because if the company doesn’t do well, they will invest in another company. And so a lot of this stuff is actually driven by shareholders and consultancies.

I traced this effect for the telecommunication industry. So there was a clear point in time when all telecommunications companies decided they had to stop being telecommunications companies and become outsourcing firms.

And you can trace that back to a bunch of reports from McKinsey, and PriceWaterhouseCoopers. And those reports got read by the pension funds, and then the pension funds, told all the telecommunications companies look, if you’re still doing stuff yourself, we’re going to stop investing in you.

And this is a big, big problem. So we have a bad situation where companies are turning into outsourcing giants with no actual technical expertise, and the shareholders are super happy about it. So it’s not easy to stop this, it’s almost impossible to stop it even.

Now, this is an important part. Like I said, this presentation is not about hating on the concept of outsourcing, or outsourcing to cheaper countries or people far away.

It is about wondering, Is this good and what is going on? And as technical people, we also really have to look at ourselves. Why are we not at the core of companies?

Why are telecommunication companies but even also aerospace manufacturers and defense companies, why does the board consists of lawyers and art students that study the history of art when they were at university, when we were studying the Maxwell equations, which is a lot more difficult.

The reason that we are not in that room, the reason why technical decisions are not getting made is that we ourselves as technical people are difficult. We are not rational about stuff. So if the company wants to outsource something that deserves outsourcing, many technical people will say, well, we actually make some really good fuses here. And we should really build our own fuses for this toaster, whereas the fuse really doesn’t matter for the toaster.

And we fight for all technology, even the stuff that is not core because we are attached to it, we love what we do. That’s true. I love what I do, I would hate to see the stuff I do getting outsourced to someone else.

But sometimes it is a rational decision. And there is a polarization in many companies and organizations where the technical people are all convinced that the management people are all stupid.

And they use words like “damagement” instead of management. And it turns out that these management people also know a thing or two about running the company, it is not a given that we as technical people will do a better job.

So we have alienated senior management by telling them one times too many that this is the stupidest idea ever, and them being wrong. And also we hate meetings. We hate sitting in meetings, we hate doing actual management things.

So if you do not show up at the meeting, do not be surprised if the company or organization makes choices that you’re not happy with. Because you weren’t there.

Then there is a final problem. Even if we work for a technical company, and the company goes wrong and declines. We just stay there. Many technical people sit there and they say yeah, this job is terrible, and, and has been getting worse for the past 20 years. And I can tell you, it will continue to get worse for the next 10 years.

But if you just continue to sit there and complain, you’re not helping. One of the real big problems here in Europe is we do not have a lot of spin offs. We have some very exciting startups that do very exciting things, but we do not have a lot of solid spin offs, where people start their own thing.

Philips in the Netherlands is a proud counter example where the spin offs of Philips are now like five times as big as the Philips original company. So that is a good example. They may be on to something there.

But if you work at a big technical company and it’s not doing the right things, then we also must do something.

So is there anything we can do? I have to admit, it’s not that easy, and I have no really good solutions.

One thing to do is take a good look at your own organization. Am I working for a zombie company? Or am I working for a company that is heading that way. And the signs are quite clear. If you see more and more stuff being outsourced, even where it makes no sense.

So for example, there are telecommunication companies that have the actual mechanics, the mechanical people that fix mistakes, and that kind of stuff. And they’re now being coordinated from a customer care center in Vietnam.

That means there are vans driving around in the Netherlands, working for Dutch telecommunications companies, And if they want to know what they have to do, they have to set up a call to Vietnam, and someone in Vietnam will tell them what they have to do is nonsensical, that is not going anywhere.

If you observe that in your own place of work, then chances are you are working at such a zombie place. If you take a look at senior management of your organization, and it’s filled with people that that are lawyers, or accountants, and there’s not a single technical person in your senior management, chances are your company is heading into zombie territory.

And because of all these shareholders, larger companies also develop a lot of procedures. Because the nice thing about procedures is that as long as everyone follows the procedures, if you mess up, it was not your fault.

And so you can sort of measure, how many forms do we have to fill out, how many change advisory boards do I have to convince before something happens. And if that number just keeps going up, again, chances are higher that you are working at a zombie company.

Now, if you have determined that your place is indeed in this kind of decline, you might hope to change that to say, Look, I’m just going to convince people that it’s better that we build our own stuff. And it’d be good that we retain the technical capabilities.

And I have some sad news. As a technical person, this almost never works. Because the technical people have been complaining about this process for the past 20 years, it didn’t help and it’s not going to help now.

Now, it’s a really harsh message. But if you think your company is dumbing down, it’s probably true, and there’s probably almost nothing you can do about it.

Really consider working somewhere else. There are smaller companies out there that are still innovating. And even though you may be very happy at where you work, you’re not going to change them. And you might be a lot happier in a smaller company than you could imagine.

And the other thing is, if you have all these great technical ideas, you have your own radar transmitter, you want to build, bet big, start your own company. There is so much investment money in Europe right now that investors do not know what to spend it on.

So if you have a good idea, there is a good chance that you will get it funded. And you can actually innovate and live the dream and build new stuff and really try to and if you think there is no money, then then please contact me. Because I know investors that that are hunting for opportunities to invest in something, if only someone were to launch something new and interesting. So please do that.

If you are lucky enough that it looks like that your company is not turning into this sort of zombie place, not innovating. And it might well be because you work for a small infant place or a small spaceflight operation or whatever.

Then become a smart outsourcer, do not fight for the fuses in the toaster. But do fight for the firmware in the toaster. The Boeing link I linked into this article, you should really read it five times because it’s so influential. And it also explains how fundamentally if you outsource all the things you cannot no longer innovate globally, because you can only think inside the box because your products are formed from stuff that you bought somewhere.

So if you for example want to integrate two functionalities into one chip, you will not be able to do that anymore because you’re only buying existing chips you are no longer able to think innovatively.

So even if your company is still alive and healthy and I really hope that your company or place of work is, read the paper and educate people on the wisdom of partnering or buying or allying on a components.

I sadly have no other concrete solutions on offer. I have tried somewhat to save the telecommunication industry, I worked really hard on keeping them technically involved. And it has failed. Where originally my company sold software, we now sell services to the telecommunications industry, because almost no one is left there that knows what they’re doing. So we have to do it for them.

And I’m happy that we do that as PowerDNS because someone has to do it. But I’m also not happy with the fact that part of the telecommunication industry has sort of devolved onto us now, which is not a place where it should be.

So I have no real good solutions on offer, sadly. I do have some more reading materials linked below. There’s another article I wrote called, “How about some actual innovation”. And it is a glorious trip through the Lockheed Martin Skunkworks and Bell Labs and JPL at Caltech in the US.

And these are very good books to read if you want to get a taste of what real innovation looked like when people could go to the office, have a new idea, sell it to their management, and actually start doing it.

And with this presentation, I hope that I have not depressed you too much. And I hope that I have given you some some ways of dealing with the current innovation climate.

And maybe that I’ve made you enthusiastic about changing things, maybe working somewhere else, or starting your own company. And, maybe then things will get better again.

Thanks.

This article is part of a series on (European) innovation and capabilities.