TU Delft lecture: Security of Science

This is a mostly verbatim transcript of my lecture at the TU Delft VvTP Physics symposium “Security of Science” held on the 20th of November.

Thank you so much for being here tonight. It’s a great honor. I used to study here. I’m a dropout. I never finished my studies, so I feel like I graduate tonight. This is a somewhat special presentation, it has footnotes and references, which you can browse later if you like what you saw.

As usual, thanks are due to many proofreaders who helped spot & fix plain errors and many hard to follow sentences. I could not do all this without your help! Also many thanks to the audio professional that helped clean up the recording. Also, if you don’t feel like reading 10,000 words or listening to the recording, try this summary:

Spoilers - click here for a summary

I expand a bit on my background in national security, and explain that I am not in favor of war, so I do think we should have technologies that are scary enough that no one will begin a war against us. And if they do, I want us to win it.

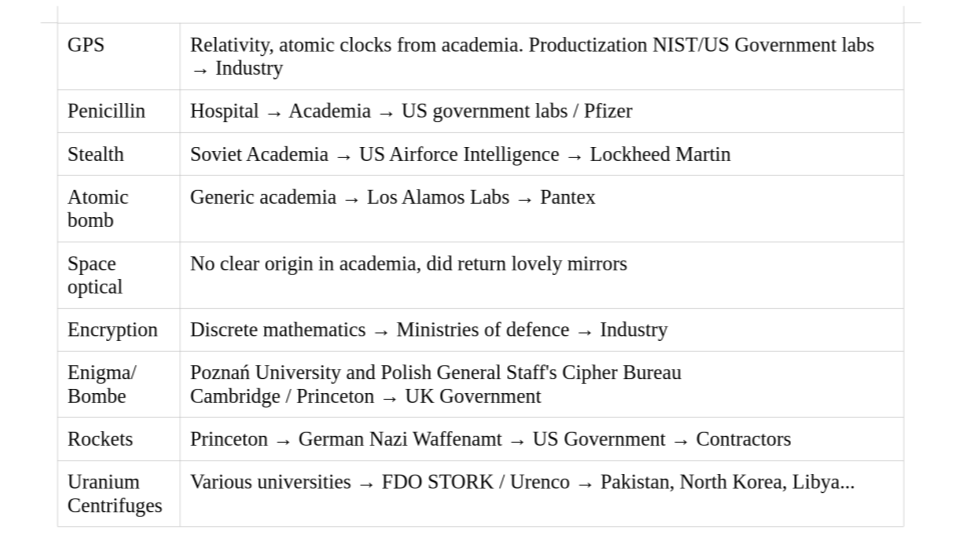

I then showcase various militarily important innovations: atomic bombs, rockets, radar, Enigma/Bombe, GPS/atomic clocks, penicillin, spy satellites.

When summarized, it is clear that universities and science played a major role in all these things. However, universities were rarely “where it happened”. Mostly these played a supporting role. In other cases the military research benefited science (Hubble Space Telescope, lithium & plutonium isotope knowledge).

Universities and societies periodically fret over how they might be leaking scientific knowledge to regimes which might militarily target us with that knowledge. In this talk, I argue universities can’t keep secrets anyhow and that they are in fact outright set up to disseminate and publish what they know. It makes very little sense to worry about what foreign students might pick up here, since it will get published anyhow.

I illustrate a bit what it takes to protect classified data, and invite comparison with how a university operates, and how it is in NO way set up to keep secrets.

I also sketch some scary developments in which the Chinese may well be ahead of us. And that we clearly do not have a lot of special technology left to hoard here.

The talk then discusses where military/defense innovation should happen. Quite clearly universities are involved, but it is likely best to have labs associated with such universities, but not sharing the same buildings and information security practices. Lawrence Livermore, Los Alamos National labs etc are great inspiration here. As are the ‘Seven Sons of National Security’ universities in China.

Europe has nothing like that. Meanwhile, “big defense” companies are also not nimble and can’t do this innovation themselves. Startups can do great things with technology that is nearly there, but they can’t do things that cost dozens of millions of billions.

There are a few labs left which can do classified research (like TNO), but these too aren’t currently known for their nimbleness.

I call for EU and NATO to also set up at least one “Son of National Defense” institute. In this way we can again innovate with military technology, and keep ourselves safe.

I’m going to talk to you about two or three different things. I’m going to tell you a lot of interesting history and physics, and I think you should enjoy that in any case. But I also come with some strong opinions, and some of you may not enjoy those opinions. In that case, I hope you will enjoy the science.

A little bit of my history. I studied Physics here in Delft. I didn’t finish it. I was a member of the board of the VvTP, which is organizing this event, which is great.

And I launched a company (PowerDNS), which initially failed. And then I thought, well, let’s join the Dutch intelligence agency, because they probably have interesting things to do. And they did have interesting things to do. And then later, I moved out into business again and became a defense supplier.

So I’m going to talk about science and security, which inevitably involves people buying defense products. And well, I was one of these defense suppliers, and that was a very interesting experience. I can tell you that.

Then later, after some business things, I rejoined Delft and I became a DNA researcher, which is a weird thing to do, but I really enjoyed it.

And then later, I became a regulator of the Dutch civil and military intelligence agencies, which again gave me a good view on how things are with our security.

I mean, I wasn’t there to study our security, but since we had to regulate these intelligence agencies, you have to know what they’re doing, what’s going on. So it was very educational.

These days, I’m a government advisor. I do various different things, but that is not super important.

We’re talking about science. So it’s good to know, do we have a scientist on stage right now? And people sometimes still ask, can I see your diploma? I have no diploma, but I do show them these two nature.com URLs. I did write this stuff. So maybe you can treat me as a scientist.

Briefly on this regulatory body and why it’s interesting. European Governments are not that much into technology. So even when they want to hire a regulator for an intelligence agency full of hackers, most European governments have said, let’s have some lawyers do that.

And they have no clue about technology. And quite uniquely in the Netherlands, they said, well, we have the supervisory board for the intelligence agencies, and it has three members, two of them have to be real judges, and one of them has to have a different set of skills. And they couldn’t even move themselves to writing in the law that it needed to be a nerd. They said, no, it’s someone with “different skills”, like woodworking or something like that perhaps.

Nevertheless, they clearly meant it could be a nerd. And for two years I was that nerd. That was super fun.

War

Now, I’m going to talk about war. I’m going to talk about terrible technology. And I want to make it very clear, I’m not in favor of war. And I really would prefer that we would not have it.

But if we’re going to have a war, I want to win it. And that makes the technology angle interesting. That’s a big change compared to five years ago, before the second invasion of Ukraine. Even a few years ago, Dutch banks, they were like, no, no, nothing with war. We’re not funding war. We’re not funding weapons. We’re not funding arms, which is interesting because you might as well be funding our lessons in Chinese and Russian then…

But it’s good to know that this attitude has changed now.

And I’m going to take you a little bit back in time, because it seems that all this war stuff was from the past, like the War Games movie in the upper left, which is in the real Cheyenne Mountain Complex.

On the right is a French fighter jet with a nuclear armed rocket underneath. I didn’t know we had that, but we do have that apparently. This stuff has become real and important again.

Science, engineering and technology

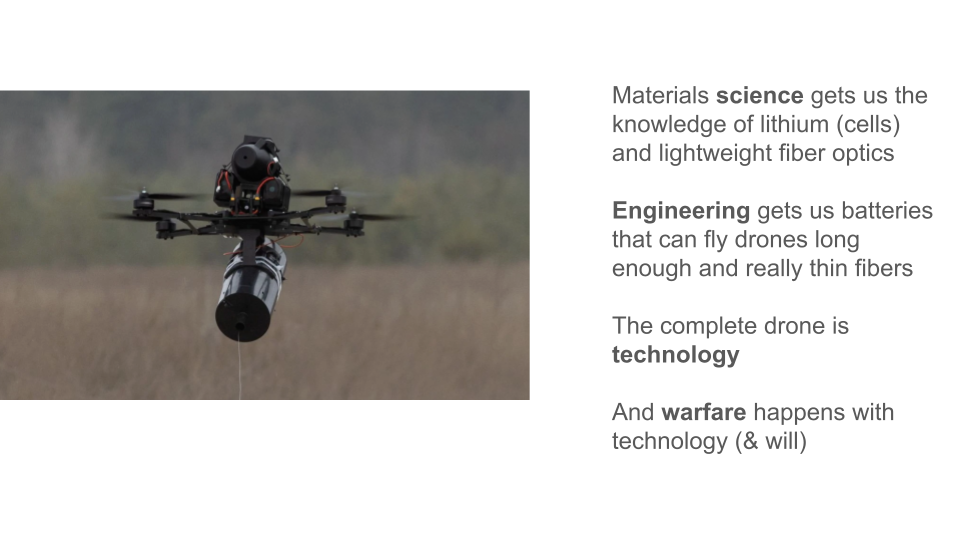

I want to spend a little bit of time on science, engineering and technology, because this is about the science of security. And then sometimes people get upset and they say, well, actually, most of the science you talk about is engineering. And they are right:

It’s good to realize that the science is for example material science. It tells you about lithium. That allows you to make, to engineer, great batteries, which allows you to make a lethal drone.

So it’s from science to engineering to technology.

Nuclear bombs

And now let’s jump into the biggest, the scariest thing that we’ve ever done in physics, which is of course the nuclear bomb or the hydrogen bomb. And this has fascinated people immensely.

At one point they found out there was a theoretical limit to how big could you make a normal atomic bomb. And then they found that if you make a hydrogen bomb, there is no limit on how big you can make it. So you can make it infinitely big. And some people really lost their mind after that.

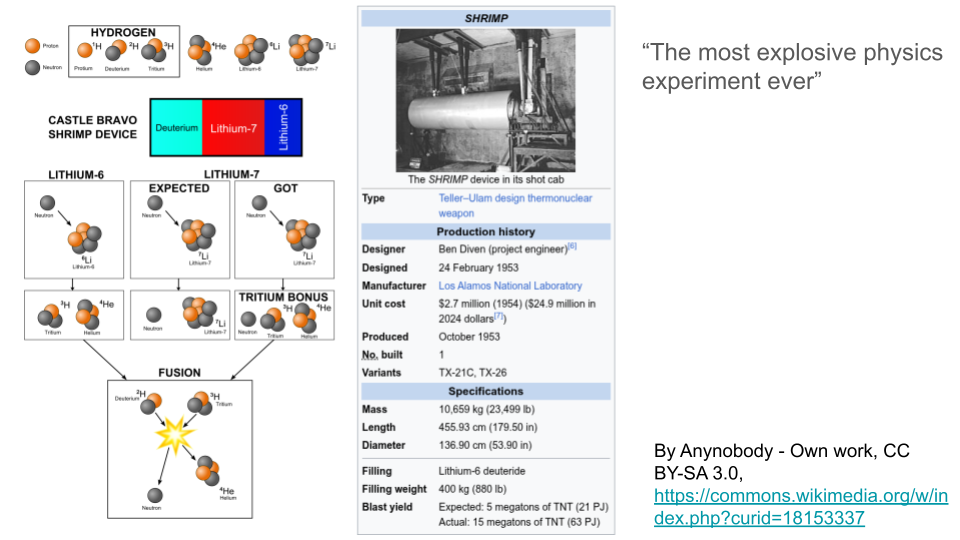

But they also got what they wanted. This is the Castle Bravo hydrogen bomb test, which was the first one that was an actual bomb. The first thermodynamic explosion came from something that was more like a building than a bomb.

And when they blew this actual bomb up, they expected a five megaton yield and they got a 15 megaton yield, which destroyed all their instruments. This may have been be the most explosive scientific experiment ever. This was actual science because the hydrogen bomb made them discover that if you bombard lithium-7 with a high energy neutron, tritium comes out, which no one had expected. No one knew this. This is why they got three times more yield than expected.

So they did this giant hydrogen bomb and they found out that lithium works differently than we knew, which is a very expensive way of finding that out because it destroyed all their other instruments.

But at least they learned this. These were actual scientists. They had made the element plutonium. And because they were real scientists, they said, now we need to find out everything about plutonium that we can because no one has ever seen plutonium.

And they tested it and they found out that if you sneeze at it, it will change density by 20%, which no other element does. And the issue with that is that if plutonium would suddenly increase its density by 20%, it might go critical.

This was a good experiment to figure out beforehand.

So this is actual science. And then time passes, lots of years pass. We try to forget about atomic bombs. They sort of disappear out of our minds, but they haven’t gone away.

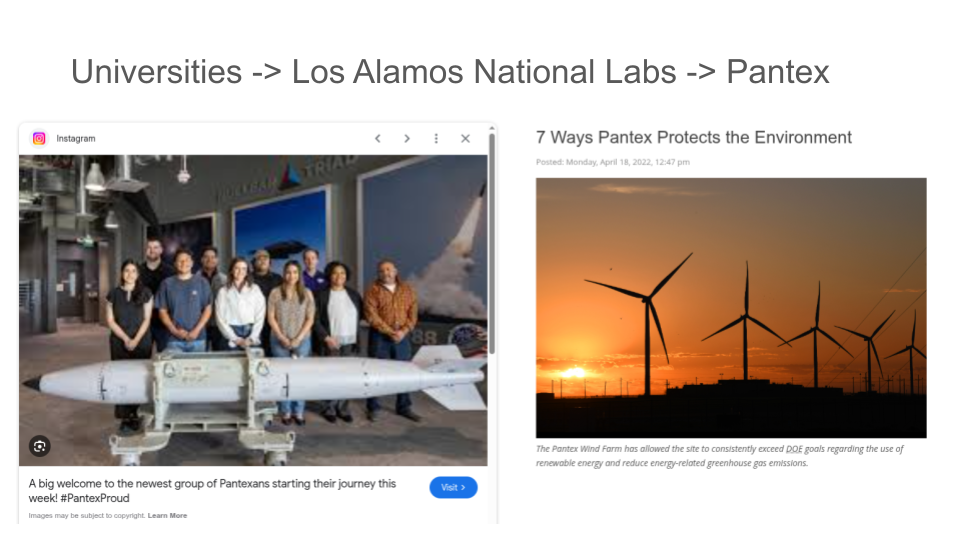

And all atomic bombs in the US are now manufactured/maintained in the Pantex plant. And this is a distressingly normal organization. They have Christmas parties and they have a very active Instagram page. If you go work there, you can get this photo taken with an atomic bomb. I don’t think it’s a real one, but it looks like one. It’s on Instagram and they have a super, super nice environmental policy.

I mean, we’re building hydrogen bombs. But look at our windmills! But there is a lesson in here. You can see here, and we’ll see that repeat in the course of the presentation. Where did the atomic bomb come from? Of course, they used all these great scientists from the great universities.

And they banded together in Los Alamos National Labs, which is a separate organization. There they did all the engineering of figuring that all out. And then finally they transferred it to the lovely people from Pantex. And we’ll see that return.

Rockets

Now here on the left is a V2 rocket:

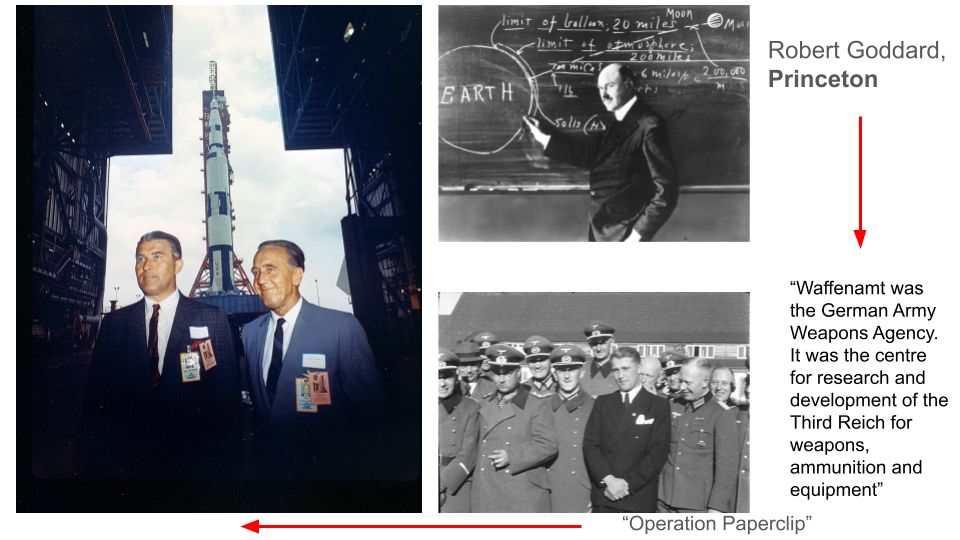

And so we can ask where did the rockets come from? Because rockets really did change our national security. We’re very worried about rockets these days. This is a V2 Nazi rocket. And it’s really good. And when the Second World War ended, all the winners tried to get all the Nazi scientists to join their camp. Operation paperclip. And the US got most of them. France got a few of them, as did Russia.

The UK got no one. Because they offered, they said, “Do you want to live in the UK or in the US?” And all the Nazi scientists said, “We’re going to the US.” Because the food is better and everything.

And the photo on the right is rather distressing. So that’s the vice president, Lyndon B. Johnson. That’s John F. Kennedy. And in the middle is an actual Nazi. Yeah, he was one of the good rocket people. So they said, “Well, you made rockets for the bad people. Now you make rockets for the good people.” And that’s how the transfer went.

We start at the top right, Princeton, Robert Goddard. He is the inventor of modern rocketry. But he invented that mostly on a blackboard. At Princeton, he once blew up a lab, and they were not so happy with that sort of applied science there.

However, he was in good contact with the Germans, who were at that point not yet bad. You could see it coming in a way. But they would just ask him questions and say, “Well, how should we make the rocket?” And he answered those questions. So in the end, the Germans became like really good. And in the photo on the right are the same people as there on the left.

These are like full-blooded Nazis making the Saturn V rocket that went to the moon. So apparently people were like, “Hey, these are good rockets. Let’s do it.”

Everyone in technology should watch this video, the Wernher von Braun song, by the late great Tom Lehrer. “Once the rockets go up, who cares where they come down? That’s not my department, says Wernher von Braun”.

This is something you should always think about in technology. When you are making something, you should care about where the rockets come down. And it’s a very good song too, by the way.

Penicillin

This is another major part of the war effort, penicillin:

Penicillin had a huge impact. Before this, soldiers would die because they scraped their hands on a tank. Which is a bad thing to do in a battlefield.

And then during the war, they went from being able to make milligrams of penicillin to making tons of it. And it’s again an interesting development. It started out with Mr. Fleming, a dour Scot, who discovered penicillin in his hospital and he found it killed bacteria. And everyone said, “So what?” It’s a very strange thing to behold. I think we are in a similar situation today.

He invented something, and people said, “Yeah, let’s see.” And then for 10 years, nothing happened. Then in Oxford, they were like, “Oh, there’s a war, maybe we should look into this.” They spent a year studying it and they found that this penicillin stuff really works. Then they went to the UK pharmaceutical companies and said, “Do you want to make this for us? Do you want to engineer this in huge quantities?” And all the UK companies said, “No, we’re not feeling it.”

Then they went to the US and they were like, “We need this to win the war.” And they scaled it up to tons immediately. But here again, you see this development from a hospital to a university doing interesting work. They did like theoretical penicillin work. And then they transferred it to Pfizer in the US and they built tons of it because they solved the engineering problems of growing it in bulk.

Encryption / decryption

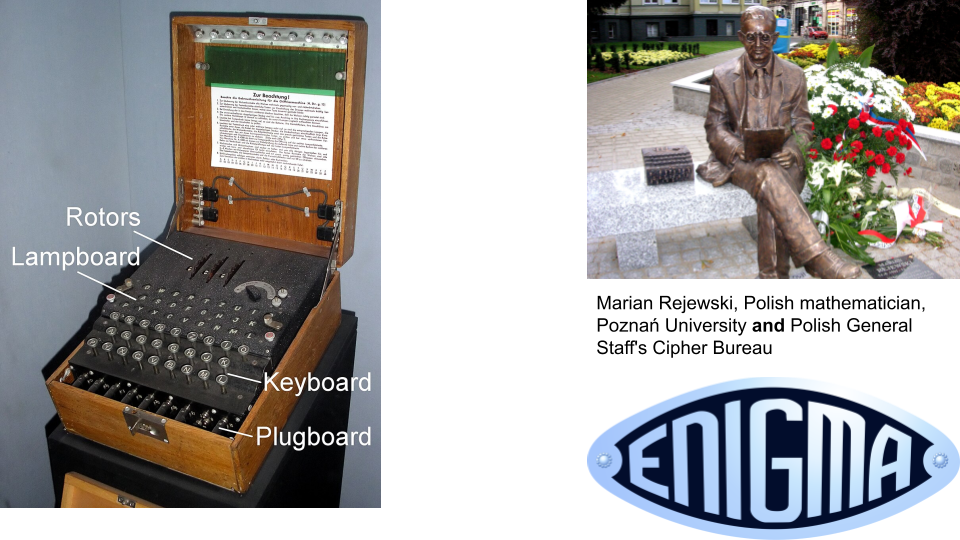

Now, here’s one of the coolest things, I think, the Enigma encryption machine:

Before the Second World War, it was not really a well-solved problem. How do you encode your battlefield communications? And it is an incredibly difficult problem to do well.

For example, if you have a codebook, it’s nice, but if someone else finds your codebook, you’re toast. So they needed a far more dynamic system and it was the Enigma machine. And that logo on the right looks like a modern logo that someone invented today, but no, the Nazi scientists apparently had great style.

So this is the official Enigma logo. And the importance of encryption, of course, is high, but the importance of decryption is also very high. On the top right is the Polish mathematician or one of the Polish mathematicians that figured out how to break the Enigma encryption.

And interestingly, he was a discrete mathematician. I was once told that discrete mathematicians really hated encryption because up to then, no one had bothered them with any practical application of what they were doing. And all of a sudden they’re like, you ruined it.

But anyhow, but the interesting thing is this guy was at Poznań University. He was like really good with this kind of stuff, but they had a separate program from the Polish general staff, which secretly recruited some of the top students there and said, you can continue studying at the university, but we’re also going to give you the secret cryptology education. And that will come back later in the presentation as a key thing.

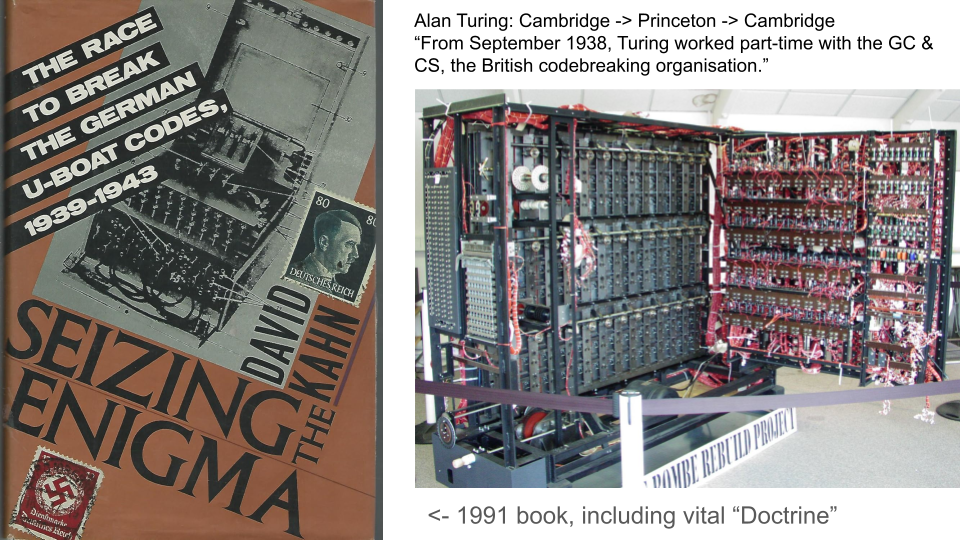

You should get this book, Seizing the Enigma, really. It’s one of the best [encryption] books I’ve ever read. The interesting thing is that in the 1940s, the Germans were like extremely good with encryption.

And it took like until 1995 until we got a public book that surpassed the knowledge of what the Germans were doing, which is a very strange thing that it took that long.

On the right is Alan Turing’s work and the work of many other people. And he built equipment (the Bombe) based on Polish knowledge, to decrypt the Enigma traffic. Again, interesting Alan Turing, his middle name was Matheson. And he became a great mathematician. So I wonder if his parents knew in advance.

But he developed this code breaking equipment. He partially worked at Cambridge University because he was super smart and he liked being at Cambridge University. And part of the time he worked for the UK government in secret, which is again, this sort of magic mix, where you say, okay, we have a university with all the smart people, but if you want to do some really clever things, maybe in secret, you might need to do it somewhere else.

Radar

Radar by now is very normal. Small boats have radar, cars have radar. But at the beginning of the Second World War, this was still a very new thing. And in the UK, they invented it, EVERYONE invented it. I mean, when radio waves were invented, it might have seemed obvious that radar would exist, but it turned out it took 100 years before people actually realized that you could do it.

So radar allowed them to spot planes over the horizon before they were coming, like a really big invention. What I didn’t know is that the Netherlands had a very active radar development also. Philips did that, Philips NatLab. And they were actually very good with it, only they were a bit late.

Backgound over at the Museum Waalsdorp

They got it working, the radar system, in May 1940. And it correctly detected the German planes. That was the last thing it did.

But there is an interesting story behind it. How did this happen? They had Philips NatLab, they had one other place, now called Hollandse Signaal or Thales now, I think. And they could do secret things at NatLab. They could build radar and not tell anyone about it. And then when they needed to actually have it made, they went to Delft University to build one part of the radar and to Leiden University to build the other part, which was for the security and the secrecy of it, because they didn’t know what they were building.

And only when brought together, it became a radar set. So this is a sort of reverse thing, where you have this sort of lab that can keep secrets, that has the university to work for them.

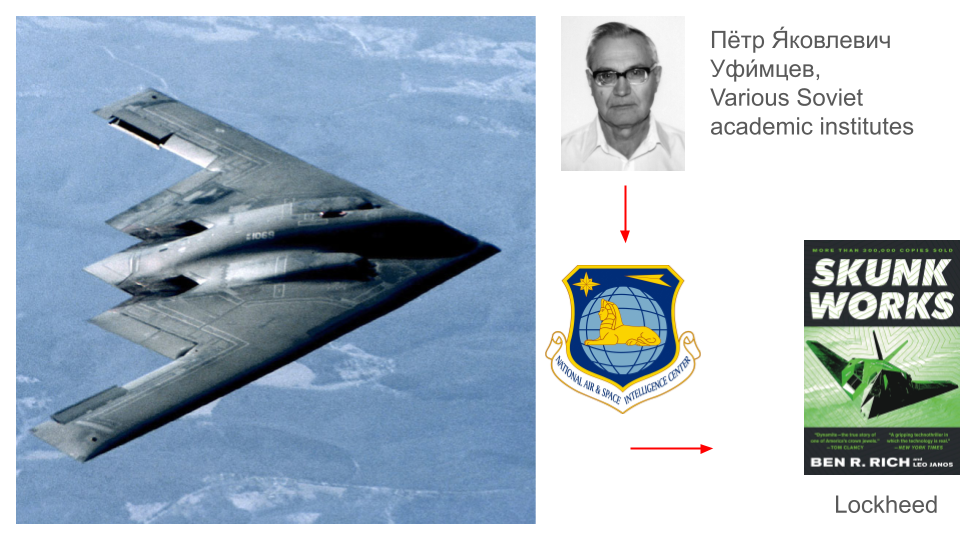

So radar, nice, but of course you want to have planes that cannot be detected by radar. And they also make those. And this is a very interesting case.

Stealth

This was like super-duper secret. In the US they called it Have Blue. And Have Blue was built on the work of a Pyotr Ufimtsev. He was a great Russian academic. He worked at various Soviet universities and academic institutes.

And he had figured out the mathematics of making a stealth plane that you cannot detect by radar. And much like the Penicillin story, the Russians said, “What use could that be?”

So he asked, can I write a book about it? And the Russians said, “Sure.”

So, he wrote a book about it. And then the American Air Force, which were like really well-equipped people, they had a whole team translating Russian science books. They were like, “There might be something in there.” So, they translated that, and they passed it on, and then there was a Lockheed engineer who read the translated book on how to hide from radar. And he was like, “Wow, we should do this.” And they did.

And so, here you see that this here actually Soviet University gave us a great scientific advance, which they had missed.

There’s another book here, Skunk Works, and you should really read that, because it’s about rapid innovation, and how this stealth development all worked, and it’s great. Now, another reverse thing:

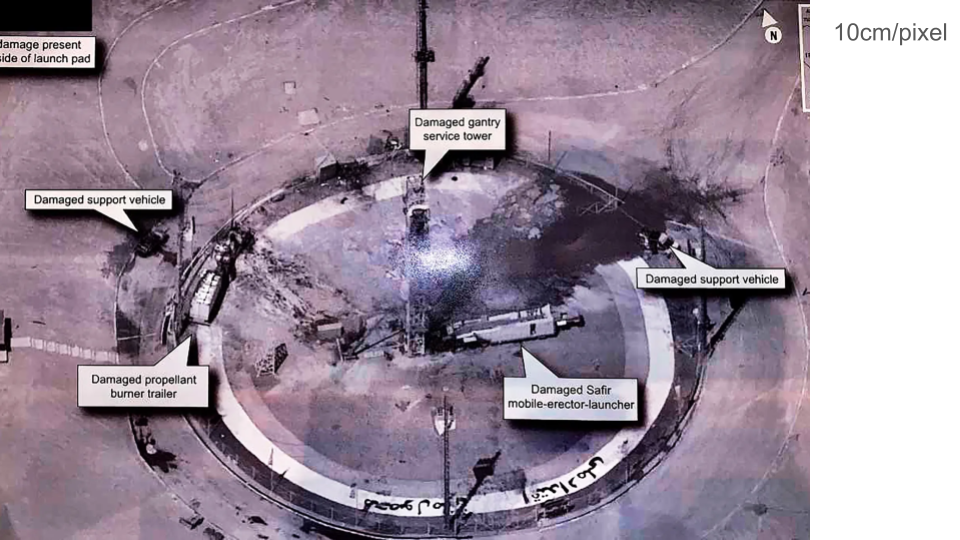

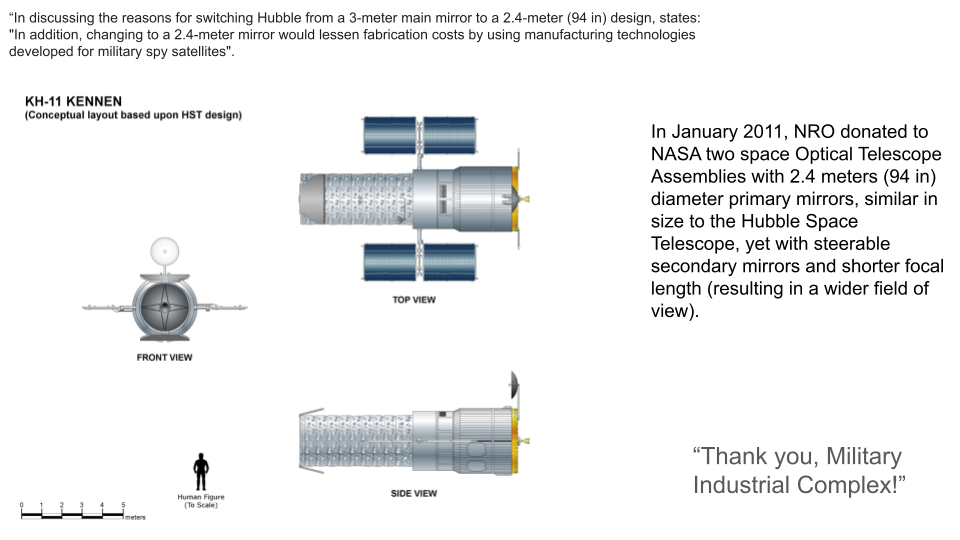

This is a view of an Iranian exploded rocket, and this is normally super classified. And it was tweeted out by Donald Trump, who thought it was a nice picture. And this is the product of a Key Hole-11 satellite, which are tremendous, and they have been like pouring billions into optics research, and you can tell.

Because you should know, this photo that you see here is actually a photo of a printout. So, the original is even better. I have seen some of the originals that come out of these keyhole satellites, and it’s amazing stuff. One day, a journalist consulted an astronomer skilled with satellite based optics and he stated “You can almost make out a face.” with this technology.

So, why is this important for us? This was not specifically coming from any kind of university, but we did have it the other way around. It turns out that these keyhole satellites are sort of identical to the Hubble space telescope, except the one looks down, and the other looks up. And at one point, when they were making the Hubble telescope, NASA was designing it, and someone came along and said, “Well, you’re planning this three-meter mirror. What if you do a 2.4-meter mirror?”

They said, “We might have a few of those.” And then, suddenly, the whole design of the Hubble space telescope changed, and this has repeated. Some time ago, they again had a bunch of spying mirrors, and they said, “NASA, can you do science with this?” So, this is the case where the military helps the science advance, which is also nice.

Atomic clocks, satellite navigation

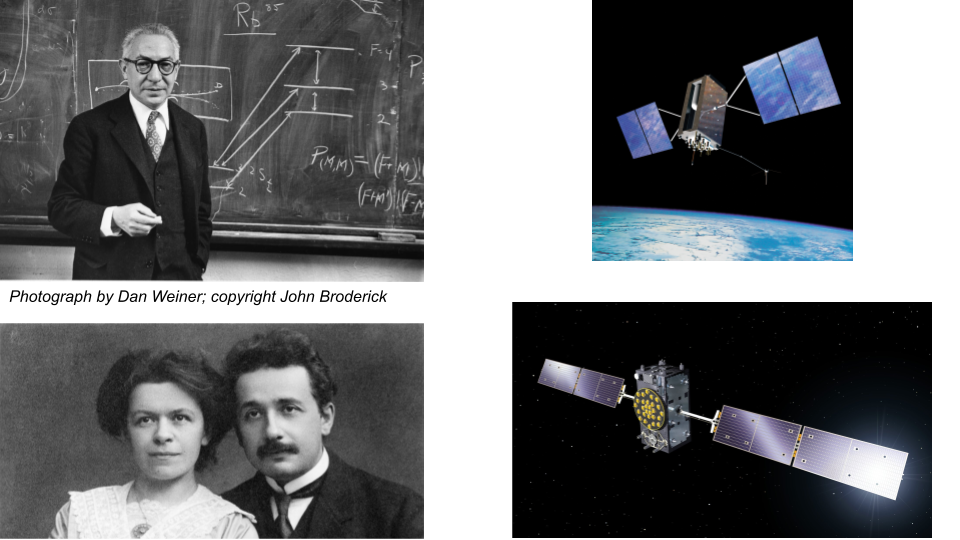

Now, I love this one. This is I.I. Rabi, a famous physicist, and he’s standing in front of a blackboard where he describes the hyperfine transitions in Rubidium:

Rabi, GPS satellite, Galileo satellite, Einstein and Mileva Marić

He invented the atomic clock, and he was a visionary, because he said, “You should build the atomic clock this way.” And then people said, “We’re not going to do it. We’re going to do it in a different way.” And 10 years later, they found out he was right. He had a Nobel Prize already, they should’ve given him a second one.

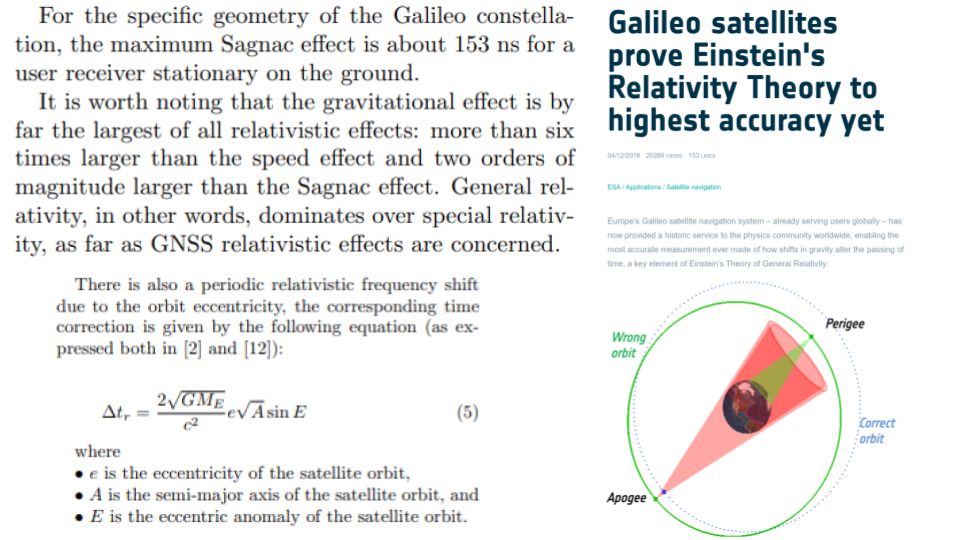

And that’s, of course, Einstein and his then wife Mileva Marić, who may have also been behind general relativity. We don’t quite really know, but I thought it was worth to mention here. And the interesting thing is, if you have atomic clocks, and if you have general relativity, you can make GPS, or Galileo, or GLONASS, or BeiDou. And otherwise, you’re not getting them.

This is a fun case. Normally, you can forget about general relativity for all your life, because you’re not going to run into a black hole, until you build a global positioning system. And you actually really have to compensate for the general relativity. And I once programmed a general global navigation satellite system localization algorithm, so the thing that takes the satellite signals and then calculates where you are. And there is this line in that algorithm where it says, “And now you do the general relativity compensation.” That’s super powerful. And if you don’t do that, it doesn’t work.

Using a badly launched Galileo satellite to test relativity, details on gravitational redshift.

So the interesting thing is, we might not have discovered general relativity, and then we would have discovered it building GPS, because it would be wrong. But we did it the other way around. We knew about it already.

Uranium centrifuges

Now we’re heading to uncomfortable territory. This is TU Delft’s most famous student ever, Abdul Qadir Khan:

And he came here to learn metallurgy, and he did. And then he went to work for a secret laboratory where they made centrifuges to enrich uranium. And he took what he knew, and he went to Pakistan, and there they built an atomic bomb.

So we should all be proud.

Already in 2002, this raised the question, should foreign students be trusted with dual-use technology? Should we have Pakistani, Chinese, Iranian people, Russians here learning techniques from us for which they might make technology with which you can wage war?

And this is what it looked like:

And to this day, actually, we still do a lot of uranium stuff here that we never talk about. It’s now called URENCO. But we should all be proud of it.

And we realized that we had a real spy here. And he was at Delft University, where he did not spy. Then he went to a special research laboratory called the Physics and Dynamics Reseach Lab. And you find, if you search for that online, you find nothing. This was somewhere, a bunker in Amsterdam, where they did all kinds of research into uranium centrifuges, and it’s like super secret.

But this was not at the university. This was at a special laboratory

Wassenaar Arrangement

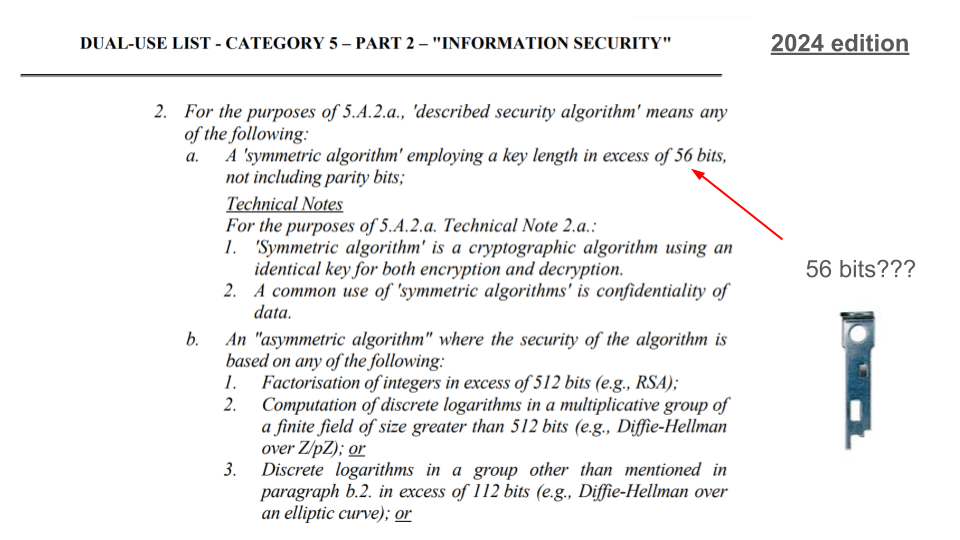

And this is also ancient stuff, the Wassenaar Arrangement, which is where the West realized that we have all this special technology, and that other countries might do evil things with our technology against us. And we hated that. So they created the Wassenaar Arrangement:

And interestingly enough, for one thing, the headquarters of the Wassenaar arrangement is in… (wait for it) .. Vienna. And also the people in Wassenaar do not know about it. Based on this logo, you can already see that it’s somewhat old stuff. And it has lists. It says, if you want to sell encryption from the West to the non-West, you must stick to 56 bits. Yeah, yeah, this is on the law books. This is for real. If you had a really old bicycle, you remember these locks, these keys. Very weak security.

“Information Security”

“Information Security”

This is sort of the official encryption standard that you’re allowed to export to China. Which is, of course, ridiculous by now, because they have excellent encryption there too. They do not need our encryption. This is a sort of old world where we in the West, we’re like, we have this special technology. And you aren’t getting it.

The whole document is also full of quotes, which is fun. So they say, we want to regulate ““lasers””. Really fun thing to read. But they said, if you have a really powerful laser, you cannot export it to China. The weird thing is that we are getting the really powerful laser from China, and we’re now not allowed to ship it back.

This is sort of old stuff. But it’s really interesting. And I think that should make us realize that technology is important for war. And wars are won using science, engineering, and technology. We cannot really neglect this stuff, because we must invent new things.

“Knowledge security” and guarding secrets

Now, periodically, people get really upset. This is where the opinion piece of the lecture starts, by the way. So this was the fun data part. Now we get a bit opinionated.

Periodically people in the Netherlands, they get really upset. They say, yeah, we have these people studying in universities, and they take all this knowledge that we have. And we’re worried about that, because they might learn in TU Delft how a laser works, and then they go back to China and make a laser there as well.

And I find this rather strange, because we talk about the “undesirable transfer of knowledge”, the transfer of technologies which may pose a threat to us. And the thing is, universities are designed to transfer knowledge. That is what they do.

And we’ll get to that later. But I want to briefly show you, what does it take to keep secrets from the Chinese? And then you have to compare that to your mental image of a university. If you want to keep classified data secure, you need all kinds of weird things:

You need to transport your data in these weird seal bags, and they’re super inconvenient. And if you have equipment, you need to put these little Do-Not-Tamper stickers on it, so that no one has opened the equipment meanwhile and tampered with it. And again, these are very finicky things, and you need to check the number of the seal also. Later, when you come back to the equipment, you need to check, is the same number of tamper-proof seal still on there? Or did someone put a new seal on there with a different number? And you need to have these Faraday cages, and special doors with iris scanners. It’s incredibly inconvenient if you want to live a life where you can say, I can innovate, but the Chinese will not be able to find out. Or the Russians, or the Iranians, or the Americans, maybe.

It’s super inconvenient. It has one upside. That’s the coffee machine on the top right. Turns out, almost all modern coffee machines, and I don’t know why, but if you have a big corporate coffee machine from Maas or whatever, they have a microphone in there. And I think they use this maybe to detect strange noises coming from the machinery, but most sort of corporate coffee machines have a microphone in there, which means that they cannot be in a classified room. Which means that you get the budget to buy a really nice Swiss bean machine. So I can really recommend working in classified environments, although it’s like super bad in other ways.

Because you get no phones, there’s no phone in the classified room, and there’s no social media. Terribly, there are also no foreigners. It’s very difficult to do international vetting and security. NATO can do it, but other places cannot do it. And there’s no daylight, because if you have a window for people to look in, you cannot do secret things with an open window. So there have to be these blinds everywhere. You cannot just have visitors around. You must receive your visitors in some special outdoors facility, which is like super embarrassing for everyone.

At birthday parties, people ask you, yeah, what do you research? Yeah, stuff. Yeah, electrons. It’s no fun at all. I’ve long worked in classified environments. It’s no fun at all, not being able to tell where you work, what you do. And also, you get no job prospects, because you’re like super good with, I don’t know, electron beams. But you cannot tell anyone. You apply for a new job. Yeah, what did you do? Stuff.

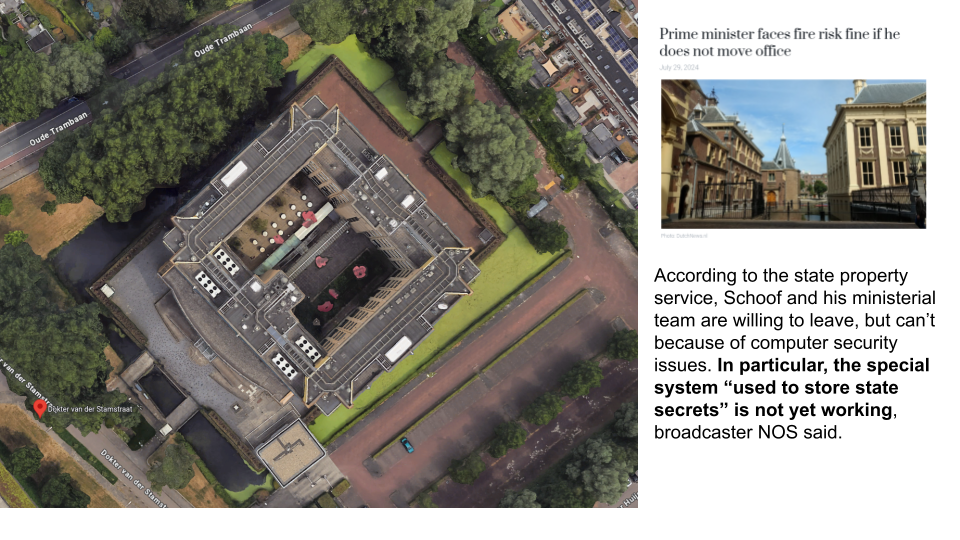

Special buildings. You get stuff like this:

If you want to do secret stuff, you need a moat. You can see the green stuff, which is actually water. This is the old (and likely future) building of the Dutch civilian intelligence agency AIVD. And you need this moat, because otherwise there’s no way you can secure this.

And that’s inconvenient, because mostly you already have an office, and it does not have a moat. And you do not get permission to dig one. So you need special buildings. On the right, you have the Binnenhof. And they said, yeah, we need to move the prime minister away from his fire hazard little tower, and he needs to get a new office. We cannot find an office that is sufficiently secure to meet the classification rules.

Enough about this, but it’s quite clear that this is not a university I just described. I mean, I checked last week. You can still walk into the physics building here and you can take the quantum computer with you. And people will probably help you push it.

Universities are designed to push out their inventions, to tell everyone. I mean, if a spy comes along and says, can I read your paper? “Yes, finally someone wants to read my paper!”.

I mean, and this is good. I love this stuff. This is, academics should be like this. But they absolutely suck at keeping secrets, because they, you can barely tell, are they at home? Are they at work? Do they work at home? Do they take the lab home with them? That has happened. If you try to confine these people to strict rules, it’s not gonna work.

Keeping secrets also requires a lot of infrastructure. You need a safe, a thousand kilo safe. You need a server that’s not connected to the internet. Try getting a server that’s not connected to the internet these days. Universities are not set up to really keep secrets. So I find this worry about, yeah, we have this Chinese guy and he’s working here, he might be able to get our secrets. You don’t need to work at the university to get their secrets. They publish them.

Universities, laboratories, companies

I want to summarize a little bit:

If you look at all the examples I mentioned, you’ll see that the universities do the basic research, and then the really cool things are, well, that’s not it. I think the university research is also really cool. But turning it into a product, into a rocket, into a medicine or whatever, almost always happens at some kind of dedicated institute, maybe close to the university, but usually not in the university.

And I think there’s somewhat of a lesson in there. If we want to do exciting new war technology stuff, these things do not come from our universities directly. And that’s also good, because if you wanted to do secret development here, I mean, good luck. It’s just not made for that.

The future, current threats

Now, I want to move a little bit to the future. I love reading books, and I also like reading fiction books about sort of non-fiction topics. And one of my recent favorite books is called Termination Shock from Neal Stephenson, in which he describes the near future. And in it, they meet with Bo, and Bo is a Chinese spy.

And he encounters the Dutch guy, Willem, in the Netherlands. You should really read this book, by the way. So he encounters Willem, and Willem says, Bo, what are you doing in the Netherlands, my friendly Chinese spy? And he says, yeah, I’m seeing how you’ll be dealing with a once-in-a-lifetime storm that is going to happen in three weeks. And Willem says, but you cannot predict storms three weeks in advance. And Bo says, we can.

Which, from a military perspective, is extremely worrying, because if you’re four weeks ahead, and know you’re going to be messed up in four weeks, and I can prepare all my war plans now, which the Chinese are doing in this book. It’s worrying. I found this one of the scariest things I’ve recently read. (In the book it is made clear the prediction was made four weeks ahead of time).

This is a drone built by the amazing Ukrainians who are working so hard, and innovating so quickly. And this, as you can see, this is a small drone with a small fiber coming out, and it comes out of this spool. And you cannot jam this drone. It can fly for a dozen kilometers. It’s fiber-optically steered, so it has no radio signature.

This was an invention that was unthinkable two years ago. Now it exists, and people want to do AI drones, which of course would be extremely scary, but you need extreme power efficiency, because we all know AI uses a lot of power. So you need to solve that problem to make an AI drone. We need to make better batteries and thinner fibers and better positioning technology.

A bit of hope, European abilities

So here’s the one bit of hope for this evening. Anything that’s going to be more efficient than current AI is going to come out of our machines, which we make here in Europe.

“War machines”

Now, this is the one thing that we have going for us. But these are war machines. So yeah, they make your new PlayStation. This is true. They also make the chip that someday is going to be in an AI drone that independently can kill Russians. It doesn’t feel like that, maybe. Doesn’t feel like a war machine. But it is. So it’s nice that we make it.

Anti-ship ballistic missiles

But then are there some other interesting challenges? The whole world of military technology is fretting about a Chinese rocket, which is ballistic, which means it really goes into space, and then it comes back at supersonic speeds, and that you can aim it carefully enough that it can kill a whole carrier ship. So there are like 12 carriers of this kind in the whole world.

If you could kill them, you win a war. It turns out this is an unsolved problem. We do not have the technology, at least not that anyone knows, that we can make a rocket that goes into space and then at full speed crashes into a 10 by 10 meter area.

You would think that this is something that is solved. It is not solved, because the ship moves. And it turns out that while you are traveling at hypersonic speeds, you get no radio reception. This is actually a very interesting physics problem to solve. Maybe you will solve it.

Maybe the Chinese have already solved it, but I do hope that we solve it before they do.

Submarines, “mutual assured destruction”

Another interesting physics part, and you can focus on the area in red, submarines:

Every major power block has these submarines full of nuclear rockets, and they are part of the very scary mutually assured destruction concept that says, OK, if we have a nuclear war, you cannot win it, because my submarines, as their last act, they will destroy you.

So you could launch a thousand rockets at Russia right now and destroy all of Russia, and then a few of their submarines would destroy America. This is the concept. It’s a terrible, terrible concept, but it is what we have.

The moment someone says, I have found technology, I have found the physics with which I can see where your secret nuclear submarines are, the concept stops working, because you can kill those submarines first and THEN win the nuclear war, for very small values of winning.

This is pure physics, and people are working on this. They are thinking about the Debye effect. The interesting thing is, if you look at the papers that are being written about the Debye effect, the most interesting ones are published by Chinese scientists, which is a little bit like these Russian scientists publishing their stealth papers. And you can think a lot about if they’re trying to sort of confuse us with science. I mean, a lot of scientific papers are very confusing, or maybe it’s misinformation, or maybe they’re simply not thinking straight.

Who is going to do the work in “the West”?

But this is a physics thing that could upset the world’s military order. And the question here is, who is going to do the work here in the West? And usually that would be NATO, and including the US, but we’re not so sure anymore if NATO, if the US will still work with us.

That means that as Europe, we have to ask ourselves if we want to invent this military future. I mean, we could also say we’re not going to invent it, and invest in learning Chinese and Russian. Or we’re going to say, no, we need to get back in the game.

But the problem there is, the current universities cannot do military research. They can, of course, do basic material science research. They could do all kinds of investigations on water and salt and reflections of radio waves. I mean, that’s fine. But they’re not going to build this satellite that can spot nuclear submarines under the ocean.

Startups can do all kinds of interesting drone things. I mean, if you have a startup, you can assemble small things. You cannot do billion euro investments. And we don’t know how that works, and it wouldn’t scale.

If you then look at the very big defense companies that we have in Europe, Thales, a very famous one, Airbus. They have become more bureaucratic than governments themselves. They have a very hard time innovating quickly. So I also do not see them just go stand up and say, “Okay, let’s do this, give us the money, we’ll invent your submarine hunter for you.”

I say “big defense” is too slow and expensive. They are not alone. We have a few institutes left, at least in the Netherlands. So we have TNO, Applied Research Organization. They have a defense department. And I also worked a bit with them, and they are also pretty slow. And they’re also very good at bureaucracy. Really good.

And so I’m a bit worried that if we want to sort of innovate, that we used to have this Philip NatLab thing. We used to have this strange lab where Khan stole all our secrets from Stork. And we have TNO, but it’s not really doing it for me.

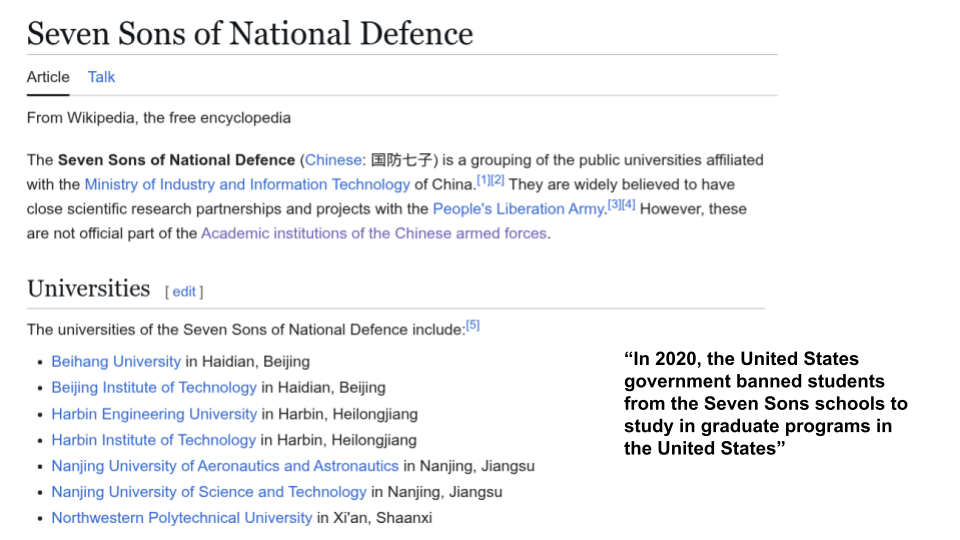

(Chinese) military research

There are some people that say, “Yeah, in China, they’re doing everything better.” No, they’re not. It’s a terrible place to live. No one wants to have kids there. But they’re sort of focused. They do have focus going. And one thing they have going, they have seven universities called — they are informally grouped as the Seven Sons of National Defense. And these are universities that are really military in nature.

And if you look these up, you will find that they’re involved in all kinds of classified research, and people disappear into them. Not in the Gulag sense of disappearing, but formerly productive scientists are suddenly no longer publishing papers. But they are like really good with high-powered lasers.

They have seven national defense universities. This is in addition to sort of all the TU Delft-like places that do research and all the fundamental. These people also train the future employees of their defense companies. We have nothing like this.

So I searched in Europe. Of course, we have military academies. In the Netherlands, we have a really good one. They have a very good GPS and Galileo expertise center there. So we do have sort of practical academics where we teach how to soldier, where you can learn strategy.

But I have not been able to find a trace of, let’s say, a military technology university. Now, it might be that they are hiding, because sometimes the military people do that, but I now get an indication from the audience that it’s not there.

The closest thing I have found — it’s very interesting — is the joint research council of the European Commission. They have 3,000 scientists. They’re in Ispra in Italy, in a very lovely place. They own a nuclear reactor. They do some cool things. But it would be like really nice if we here in Europe — I mean, it would be — we should be big enough.

I mean, like 450 million people in Europe. If you add the NATO countries here, it adds to 550 million. We should be able to set up some kind of institute!

I mean, we have institutes for everything. We have huge agricultural research organizations. It would be nice if we had at least one “Son of national defense”. Maybe two later.

Now, of course, this costs money, costs real money. And the European Commission came up with a plan that was called Re-arm Europe. And they had to change the name, because they were countries in Europe that said, yeah, we don’t want to rearm. I’m not sure what these people are thinking. But Spain and Italy said, that sounds too war-like.

So it’s now called European Defense Readiness. I’m not deterred by that. But they said we are going to spend 800 billion euros on defense capabilities in Europe. Like, super nice. I mean, that’s like real money. And I think it looks like they’re all going to spend it on buying rockets and launching satellites, which is nice.

But I would very much recommend them to say, well, do not use all that money to buy American rockets, but set aside a few percent of that and actually rebuild this knowledge thing and stop obsessing about the fact that we have a number of Chinese students here who are stealing information that was already public.

Stop obsessing about that and start building some actual military research institutes with very close ties, of course, to these universities, because that’s where the knowledge comes from. Now, this plan is not entirely new, because that would be amazing.

In the Netherlands, we have the Dutch funder, NWO, and they fund the universities, and they have made available 30 million euros. Three zero. And I’m sure that’s going to put the fear of God in the Russians.

But at least this is a first step where the Ministry of Defense has a role in saying, okay, dear universities, we would love you to research this kind of material or this kind of submarine detection technology or whatever.

But this is a very small first step, but at least it’s there. And personally, I really miss places like Phillips NatLab. I would love to have a defense laboratory that could scale up these things in secret.

And even the weird physics dynamic Stork laboratory, I would love to have that back again, but then without the Pakistani spies. That would be nice, because those places would be able to do secrets.

Summarizing

Now, summarizing, without scientific and engineering advances, we get no new technology. Without scientific and engineering advances, we get no new technology. With no new technology, eventually we get an adversary or an enemy that simply outclasses us. They have drone swarms that we can do nothing against, that have rockets that destroy all our ships in the first 15 minutes of a war. That’s bad.

It’s also to be noted in this presentation that we got a lot of spin-offs from defense research that actually made some really good science, like the Hubble Space Telescope, but also what we learned about lithium and other things. Batteries are a nice example, which were really stimulated by the military purpose.

So investing in military research, eventually a lot of that comes back to you. We should stop worrying really about universities and their secrets that they’re sending abroad. I’ve said this five times now I’ll say it six times.

If you feel differently, go to a random technical university and just walk in there and see how much equipment you can just take with you. Before someone notices. It’s probably quite a lot.

We currently do not have good paths in Europe for defense innovation, because we rely on the defense giants to be innovative, which they are not, or we are hoping that universities maybe spontaneously create new rocket technology, which they’re also not doing.

There is money on the table. I mean, if the European Union says we’re going to spend 800 billion euros, I mean, if you would spend 8 billion of that, that’s already more money than I can imagine ever spending, that would be huge. And I miss the research labs.

Books

And with that, this is the list of books I recommend:

- Making of the Atomic Bomb

- Ballistic Missile Defense

- Skunk Works

- The Cardinal of the Kremlin (FICTION!)

- Seizing the Enigma

- Splijtstof

- The Idea Factory: Bell Labs and the Great Age of American Innovation

- Termination Shock (FICTION!)

These books are like super fun and back up my stories, so that you can check, did Bert just make that up, or does he actually have references?

And with that, I thank you for your attention.

Questions

“You mentioned that startups are not the most suitable to do these military innovations, or they’re not everything.” (here I rudely interrupted the person asking the question, apologies).

They could do it, but there are two problems with it. One, you would have to teach the startup how to “do secret”. And doing secret is actually difficult. You need to learn that, you need equipment. For example, if you are at Yes Delft, and I love Yes Delft, they have these very thin walls there.

And the moment you do anything, even remotely at the lowest classification level, someone will come along and say this wall needs to be like five times as thick. Otherwise you cannot do it. And so these people will have a difficult time. So keeping secrets is one thing.

The other thing is it quite quickly costs a lot of money. If you need to get actual hardware, actual lasers, actual explosives, or whatever. Whereas if you are a computer startup, you need like a computer, and you can get to work, and you don’t need an explosive range.

So of course they can do things, especially in the drone field, you are seeing something. But there are other cases where people say, look, I just need to drop a million euros now on kit, which is harder for a startup to do right now.

So if you have like 1% of ReArm Europe, if we have 8 billion euros, you could give someone a laser beam.

“So my question was going to be what can startups do to enhance strategic autonomy? So if I hear you correctly, it’s focus on the computer.”

They could do a lot, but it is not easy because, for example, I worked at a company where we did classified stuff for the government. And you need to spend a lot of time with the government to get accreditation for that. They are also not used to that. So it is not, I’m not saying it cannot be done, but right now it’s not what startups are used to doing. Let me give you, you mentioned strategic autonomy. Let me mention one thing. Doing this stuff means having your own infrastructure to store data. Modern people store everything on OneDrive or Dropbox. Or TikTok. It’s very difficult for people to say you need to get a server in your office. People no longer know how to do that.

And in fact, whole ministries of defense no longer know how to do that, but they sure expect their startups to do it.

So again, maybe as a positive suggestion to come out of this, you might maybe say, okay, if we want people to innovate, maybe we should prepackage the kind of hardware that you need to do information security for yourself.

Or maybe we should do it for yourself so that you even can begin doing interesting work without having to put it on your Google Drive or from your Alibaba PC. I mean, you’re not going to conquer the Chinese from Alibaba, let me tell you that.

“I was wondering, what do you think about the U.S. military complex, and are there lessons that we can learn from that or do you think we should learn from that?”

Eisenhower, I think already warned for the U.S. military industrial complex and companies like Lockheed Martin are now larger than many governments. And also, they work like governments. And so what you see is that large defense organizations always fall asleep in peacetime, which is fully understandable.

And then they wake up when there’s a war. And if you see the rate at which Ukraine can innovate right now. Two years ago, I was briefly involved with the Ukrainian plan to make better drones. And it didn’t work out, so we didn’t do it. But I still remember the plans that we made.

And if you see what is flying right now, that leaves all these plans in the dust. What they are doing right now is so much more advanced.

Whereas if you look at Thales, or Lockheed Martin, or Airbus. I once actually worked with one of these companies on a project, and they said, yeah, we need to change the plan. And then they were like, okay, we’ll reconvene the planning committees. Whereas we were like, oh, we’ll get on the plan next week.

And we had to learn how to work with them. We had to give them room to do the meetings about the meetings about the meetings. So, yeah, you can learn a lot about them.

The other thing I learned, which was rather scary, is that some of these defense companies spent a lot of time lobbying. Like, a lot, a lot. In which they influence decision-making. And they do that to enhance their own success.

And that was worrying because I saw the intensity of the lobbying effort that was being made. And I thought, I hope that you would apply the same intensity to developing better weapons.

So this is an ongoing struggle. How you can get the lean sort of defense company that can move quickly. But on the other hand, sometimes you just need to move billions.

And that’s something that Thales and Airbus can do really well.

But that’s the other thing, it’s very hard to square that circle. And what you often see is that there’s a small company that innovates to a certain point and then they get acquired.

Which is actually not even the worst thing to happen.

Because then you get the best of both worlds, a small company that can innovate quickly. And then when they need a billion euros, there is someone that has a billion euros.

But the big defense is definitely not an example to follow, but it is what we have.

“I have a question about a model that exists in the United States, whether it would be applicable here in Europe, including the Netherlands. You may have already answered by saying we need more research laboratories in this country than elsewhere.

In the United States, Lincoln Laboratories and xx Laboratories are both part of MIT, but they do highly classified research, JPL at Caltech, Los Alamos, I think it’s correct, it’s still run by the University of California, used to be an industry, and I worked in Lawrence Livermore Laboratory, which is run by the University of California. There is the connection with academia that people who are on the academic staff at the universities have the opportunity to work or consult at these closed, secretive research things. Would that work here?”

I want it to work. We should give it a try, because we have not done that, but I think it’s a great example to follow. You also saw that success from the Polish cryptologists that were able to break the Enigma code. They had a similar thing going, with the university, and then there are some buildings near the university which are operating under a very different regime. So I would love for us to try.

I can also see how it would be difficult, because we do not, in the Netherlands specifically, have a large entourage of people surrounding the government. So in the Netherlands, if you’re in government, doing secret stuff, or you’re outside of the government, and they are not very good at having these people giving students a security clearance, for example. Our security clearance process is also rather difficult.

I would love this to work, but it is not going to be easy.

“I was just wondering why are we investing so much money into this? Into weaponry. We must also cut across into diplomatic and peaceful alternatives. Isn’t this just going to increase tensions and cut opportunities to diffuse tensions peacefully?”

So this is a very good question and I think I have a link on this. This is called the security dilemma and if you get the PDF version of the slides it has a link to the security dilemma. And this is fundamental to everything that we do. So if no one built arms we would probably also not have war.

And then maybe we could talk it out. And then maybe one of the two countries or blocs or whatever decides to invest in arms. And then the other one says now I need to do that as well. And everyone has been thinking about this since ancient Greek times. Is there a way out of this security dilemma? And it has not been found. So I would love us to say let’s work it out.

I’d love to invest in all kinds of other things but sometimes other people make choices for you.

And if we ever solve this then we can shut down all these conferences and start doing much more fun things. But for now we have not solved that dilemma because if right now we say let us stop with the arms and stuff then quite soon we speak Russian. Because they are not going to stop. But this is not an easily solved problem. But I much recommend reading the security dilemma page to see the ancient Greek thoughts on this.

“I am concerned that we are running out of time. Money is really, really great. Access to the university is really, really great. Are be running out of time. And when do you think it is going to go from a high ball to a hot ball? And then we actually have to have action rather than just merging on talking about it.”

So it is your question when are we going to take action?

“Yeah. When do you think, how long do you think we have until it becomes a hot ball and then we have to actually take action? How long do you think?”

That is a good question. I cannot predict the war because I don’t know. I can predict how slow we are reacting right now. And it is speeding up. We are now hearing more talk about we should actually get on it. The military and complex is waking up and speeding up. But it is still happening in a very slow way, it is not in a hurry yet. And I worry about that. And how the wars will develop, I don’t know. But I think we are not doing enough right now.

“Thank you for the presentation. First of all, I would like to say you have got a beautiful tie.”

Let me tell you, I have stored this one for 30 years! Just for this occasion!

“We are all very glad you did. My question is, so in the current situation with universities in the US, it is not as favorable for scientists to be there. And countries like France have tried to position themselves to take away scientists from the US and bring them here to Europe. Do you think this is a good tactic? It is kind of a similar tactic to what the US did after the Second World War. Do you think this is the way that Europe can get ahead in this arms race? Or do you think they should invest all of them and do all the innovation and science in-house? Or should they try and back the scientists from like the China, the US, Russia?”

So I have met many upset European scientists that do not get funding. And they are like, hey, I do what I do. And now an American will come here and do what I do.

A big difference also was that during the Second World War, the US did not have a very large university system full of physicists. So they actually had a lot of room to say, hey, come here. They weren’t competing with sitting American scientists. So I’m sort of in favor of it, of course, but you will find… Let’s say the people that are doing the dark arts of classified research, those are not the ones that are going to move to Europe. Because they’re also not allowed to share their research.

So while it’s interesting to get these very good scientists here, I don’t think we’ll immediately get all kinds of secrets on how to make ballistic ship carrier killer from them. Because they’re not taking their notes with them.

And with that, I think we round it off. Many thanks for the good questions and all your attention. Enjoy the rest of the evening!