A Science Experiment: published!

And we’re back! As noted in part 1 and part 2 I thought it might be possible that I had discovered something interesting in biology. Lacking an academic peer group, I had decided to use a series of blog posts to gather feedback and to keep myself honest.

I’m very pleased to report that this process worked! I just received word that Nature Scientific Data has formally accepted my paper “SkewDB, a comprehensive database of GC and 10 other skews for over 30,000 chromosomes and plasmids” for publication!

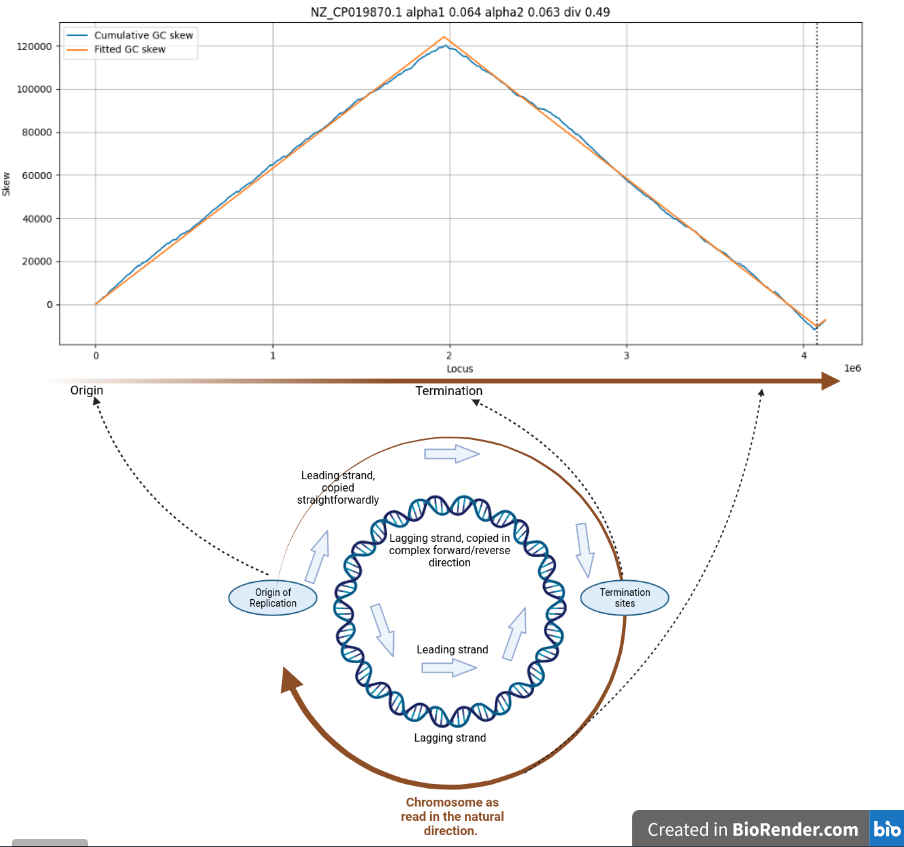

Cumulative GC skew for C. difficile

Now, it is reasonably exceptional for an outsider to get something like this published, let alone as a sole author. Many people helped me to make this happen, so in return, here I’d like to outline a bit what I did, as I think it might serve as useful inspiration for other junior science people.

Please note that I am of course not a real expert, having only done this on my own once now (although I was a co-author before on another paper). But I’ve checked around and the advice below is straightforward enough that it should probably be helpful in most cases.

The really short version:

- Are you sure you want to publish your research in a journal? It might take six months or a year (or more)

- Get help to figure out the right journal(s) for your research

- Make sure your work looks as normal, as reputable as possible:

- Publish on the right preprint server (but do ignore all the predatory journal spam!)

- Deposit your data in public (Dryad, Figshare)

- If you use software, also deposit that (Zenodo)

- If at all possible, make your data processing/graphs/tables reproducible, and also publish that script/playbook/notebook

- Have a decent homepage / profile

- No shortcuts!

- Journals publish detailed guidelines on what your manuscript should look like. Look exactly like that. Be a model submission

- Write a cover letter that understands what the journal is about

- If need be, write response letters to reviewers that understand what their life is about

Are you sure?

Getting your work published is a many month affair. For me it took around six months from beginning to end, and this is regarded as ‘fast’. Also know that around a million papers get published a year in biology/medicine alone. Getting published will not by itself set the world on fire.

On the other hand, getting your work accepted does mean people will suddenly take you a lot more seriously. So it might be worth it. But don’t do it just for fun.

Oh, and be sure you actually have a result to report!

Picking the right journal(s)

I think the first critical success factor was indeed sharing widely that I would be doing this. Various people on Twitter chimed in, some with crucial help. One extremely helpful anonymous person pointed me to the right journal for this kind of research. I would never have found this out myself. If you submit your work to the wrong journal, it is not ever going to work. Sadly, it is not even trivial to find this out – there are zillions of journals. So do seek help to figure out the right place.

Be aware that open access journals tend to ask for a publication fee. This could be extremely expensive. Even more traditional journals may ask for real money. Do find out beforehand. Some (open access) journals have agreements with certain institutes to waive the fee, so you might be able to get creative there.

Predatory journals

That brings me to another topic: predatory journals. It is becoming ever harder to figure out which journals are legit and which are fake. Even reputable publishers now have questionable journals in their portfolio.

This is extremely important because of another critical success factor: the preprint. A long time ago manuscripts were deep dark secrets, only to see the light once they got accepted for publication. This could take months or even years. These days, many articles are first published on preprint servers, which allow people to already weigh in.

As an outsider or junior person trying to get your stuff published, it is important to look as reputable and normal as possible. Doing a preprint greatly contributes to this.

But here’s the rub – once on a preprint site, you’ll get inundated with spam from predatory publishers. I received unsollicited email claiming to be from:

- “EC Microbiology”

- “Virology Current Research”

- “Bacteriology & Parasitology”

- “International Journal of Plant, Animal and Environmental Sciences”

- “American Јоurnal of Traffic and Transportation Engineering” (??)

- “Research Features”

- “Research Outreach”

- “Journal of Clinical and Cellular Immunology”

Now, I’m rather jaded where it comes to unsolicited approaches, and I know what a real journal is supposed to look like. But even then some of these titles almost look like the real thing. You could easily fall for this stuff. Some help is available, like from the library of the University of Massachusetts Lowell, but there you can already see how hard it is. Some predatory journals hijack the name of (formerly) legitimate publications, for example!

I think that as a rule of thumb you can safely just ignore any unsolicited journal email you receive that references your preprint, unless you are truly well known in your field, in which case you are not likely to be needing this page to help you along.

Preprint server

Nevertheless, getting your manuscript on a reputable preprint server goes a long way towards making you look like the real thing. Seeing your work on arXiv, bioRxiv, medRxiv somehow already makes you look more reputable. These preprint servers perform very minimal screening, but still it is like the world’s tiniest stamp of approval.

Depositing your data and software

Science is currently undergoing somewhat of a reproducibility crisis. The trend is towards ever more open science, and as an outsider, you’ll have to lead the charge. Seasoned professionals may be able to get away with “trust me the data is good”, or the evergreen “data available on reasonable request”. But you can’t rely on your reputation (yet). So everything has to be out there.

I’ve worked productively with Dryad for data and Zenodo for software. These make it easy to cite your own work.

Reproducibility

This is a big thing these days. There is a lot of research fraud. People will worry that the research you publish might not be real. There are a ton of (medical) results that somehow do not reproduce.

Now, depending on your research, you may be able to publish your data, software and even a setup that uses these two to reproduce all the graphs and numerical claims in your manuscript. Not only is this useful for yourself, it will go a loooong way towards convincing people that your work is legit.

“Look the part”

People will search for your name online to figure out if you are legit. Make sure that you have a representative homepage that actually lists your research. In addition, you can create an ORCID iD which many scientists use to identify themselves even if they change institutes. If you’ve ever published anything that looks remotely like a science paper, you can also add this to your profile. Similarly, you may find that Google Scholar is willing to make a profile for you.

Don’t leave this to chance - if a search for your name leads to weird pages that do not reflect what you do, spend some time to look like the serious researcher that you are!

No shortcuts: all the optional things

During the submission process, you may be asked to fill out forms, do surveys or supply figures in an odd selection of formats. Just do all of this, even the optional things. If the journal suggests that you optionally fill out a metadata descriptor on some site, hop to it. Because, and I’ll keep repeating this, you have no credits to burn on things you could also just get right.

Journal requirements

Journals publish (sometimes unreasonably) detailed lists of what they expect manuscripts to look like. What sections should be in there, how long they should be, how many graphs are allowed, what the graphs should look like, where tables should go. In terms of contents, they also have strong guidelines about what kind of research a journal is interested in.

Treat these guidelines like the holy writ. Whatever they say, just stick to it. Go over all the documents. And even if you feel that something doesn’t matter, it does. If they want a comma in “30,000”, you put the comma there, even in the graphs.

Because the thing is - almost no submission to a journal sticks to all these rules. But the other submitters have credit, and you don’t. If you get all this stuff right, you are already ahead of almost everyone else!

Cover letter

Now, I’m of course not that much of an expert. But I have quite some experience reading submissions for proposals and grant requests and many letters don’t get the essentials right. I’ve also seen many journal board people lament the quality of cover letters.

The thing is, these people go through a lot of submissions. You’ll need to sell your work succinctly. Study what a journal is about. Read whatever you can find. They’ll often just come out with it and say things like “we want to publish the latest and greatest in seahorse reproductive research”. Good.

If your paper has anything to do with seahorse reproduction, by all means write a letter that says “this manuscript details surprising findings about egg formation in seahorses, a vital part of seahorse reproduction”.

Don’t feel bad about pandering to the audience - as long as your research is actually about seahorse reproduction, be enthusiastic about it. Make very clear why your research would interest their readers & match the journal’s mission statement.

Also, at this stage (and all other stages), do get all the details right. If you are addressing dr. Big C. Fish from the Journal of Seahorse Reproductive Research, do not write your letter to Big D. Fish from the Journal for Seahorse Reproduction Research. It may seem petty, but don’t burn your non-existent credits on such avoidable mistakes!

This Twitter thread from Vineet Chopra (deputy editor of Annals of Internal Medicine) has further good advice.

Peer review response letter

Peer reviewers will almost certainly come back with serious questions or even requests for substantial revisions. Don’t be put off by that. Not all of the reviewers may have read your work as well as you hoped. It may also be that they misunderstood the intentions behind your manuscript. If so, you may have yourself to blame.

Realize that these scientists have other things to do than review your paper. They aren’t getting paid for any of this. Study extremely well what they said. There may be whining in there, but in all likelihood they are (also) making good points. As an outsider, chances are extremely high that your reviewer has a decade+ more experience than you in your chosen field. You may be on the receiving end of some free mentorship.

I’ve also been told that some reviewers would prefer that you had written a totally different paper. That is obviously not something you should be taking seriously.

Do understand that you are not doing battle with peer reviewers to see who is right the most. Figure out where they are coming from and why they are saying the things they are. It may be that you are attempting to upset some dearly held paradigm and that the resulting friction causes reviewers to be extremely critical of your assumptions. This may actually mean you are on to something important.

It pays to spend real time on this. In your response letter to the peer reviewers, make sure you address everything they said. For my own paper, I assigned numbers to each and every remark, and used a spreadsheet to keep track of if I had addressed them all. It may help to batch related remarks - they may even cancel each other out, which leaves you with less work. Make your response as easy on the reviewers as possible, for example by repeating their remarks and addressing them inline.

The journal may also ask for a separate response letter in which you could for example summarise the overall responses of the peer reviewers. This might be a place to contextualize a bit, and perhaps appeal to the priorities of the journal. For example, if a reviewer noted your work upsets a dearly held paradigm, you could remind the editors that it is their mission statement to publish the latest research, and that upsetting paradigms is a hallmark of new results.

Summarising

As a junior scientist or a complete outsider, you’ll have to get everything right. The good news is that a lot of established researchers do not in fact get everything right. By clearly explaining what your work is good for and how it aligns with what a journal wants to publish, by making sure you dot every i and cross every t, by adhering to all modern best practices and making sure “you look the part”, you can raise your chances of getting published tremendously!

Good luck!