Keynote opening Digital Commons EDIC: Moving beyond the Digital Uncommons

Last Thursday, 11th of December, saw the launch of the new Digital Commons European Digital Infrastructure Consortium. In attendance were delegations from the launching member states (and the observers). Also present were the many forefathers (and mothers) of this initiative.

Of particular note, the launch also included demonstrations of LaSuite software from France, as well as the OpenDesk software from Germany. The Dutch government showcased their amalgamated suite MijnBureau, which joins parts of the German and French initiatives.

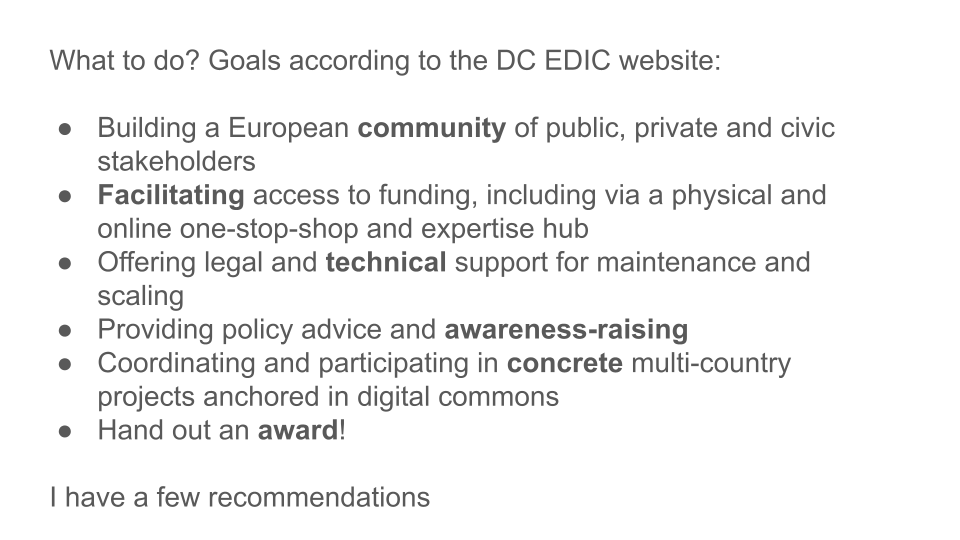

Now, I’ve not been part of the DC EDIC preparations, but I’m a well informed outsider, so I was very pleased and grateful to have been invited to do a keynote address. For preparation, I read the official website of the DC EDIC, which at that time (archive copy) had all kinds of worthy goals outlined, but these seemed relatively modest. Coordinate, facilitate, create a hub, policy and legal advice, hand out an award, that kind of stuff. This was also what I prepared for.

Celebrating the kickoff of the DC EDIC with the Visio video conference software from LaSuite

Yet at the actual meeting, things were much wilder than that. There were rousing speeches outlining in very clear cut terms just how dire Europe’s situation is in terms of digital autonomy, and clearly stating that there is an urgent need to take action. There was talk of actually regaining digital autonomy, so we can write government documents without sharing these with the US first. Based on the case of the International Criminal Court, it was clarified that Europe is now very vulnerable to US sanctions, and that such sanctions are actually happening.

My talk now looked a bit anemic compared to these strong but very welcome words. I was especially happy to hear some tremendous clarity from Thibaut Kleiner, director over at the European Commission’s DG CONNECT. A few weeks ago I attended another EU-heavy event, where there was a lamentable assumption that things were still normal in the US, or would soon be so again. No such confusion was to be heard during the DC EDIC launch. Chair Art de Blaauw also delivered a very clear message.

This was encouraging, and I wish everyone all the best with the new EDIC, and I hope that with good thinking, we can achieve great things. I can well imagine this EDIC becoming a nucleus of great change.

Spoilers - click here for a somewhat detailed summary of my talk

The tl;dr of my talk below: I start with outlining in some detail just how messed up things have become. Not only are we completely dependent on US technology, we’ve also culturally have come to accept that it is fine to do government communications on platforms that immediately surround your communications with conspiracy theories and antivax content. Also even our data protection authorities and secret services don’t manage to prevent having their sites and newsletters contain US trackers and cookies. That’s how hard it has become, both technically and culturally. I then expound a bit on the difference between digital autonomy and digital commons, where I conclude that it is best to aim for these commons, and not just autonomy.

For the EDIC, I have some modest policy suggestions (based on the modest goals I found online), and even now that the ambition appears to be far larger, these are still useful. Educate governments on the need to do things differently, but also tell the digital commons technical people & ideologues that even good and free ideas need 1) marketing and “sales” 2) good “as-a-service” providers and 3) removal of needless barriers, as we get no credit for tech being European.

The EDIC could also be massively useful in gathering and highlighting shining examples from member states, examples that show that it can be done. Through norm setting, the EDIC could also itself show what is possible. Specifically, the EDIC could also help regain email (SMTP) as a digital commons.

I round it off with an important warning: if we are aiming to replace Microsoft 365, as the German state Schleswig-Holstein is doing, we will only get one chance. Before we try that, it may be good to first lay the groundwork, which the EDIC is very well placed for to do.

The actual talk

I hope to entertain you and inform you with some contrarian views. But know it comes from a good heart.

The complete slide deck is here.

So, before I start, I have to tell you a few things about my background. I’ve been thinking about digital autonomy for a very long time. I’ve worked a while for the Dutch government. I’ve been a regulator for the Dutch government. I’m currently an advisor at a number of places within the Dutch government. But I must stress, I am here on my own behalf. Because otherwise they’d never hire me again.

I’m going to say a few critical words today on our initiative. But know that it comes from a place of love. So people say, Bert, are you just bashing the EU? And I point you to this picture of me with my EU hat. I love the EU. And I want this to work.

A lot of people today have been called the father, grandmother or godmother of this initiative. I would like to say I’m sort of the critical uncle who always asks difficult questions. But that are you okay with that because you know he loves you.

I’ve been a government employee. I’ve been a government buyer. I’ve been a government supplier. Everything I do is open source. We’ll get to that. But I’ve also done like real business stuff with money. And I hope that that can sort of enlighten us today.

So all of society now runs on computers. Computers which are mostly not ours, which is a worrying thing, actually. The computers have become even more important, even as the world has become scarier.

So we now rely on computers to keep us safe, and these computers are not under our control. And ever more important things are heading towards computers that are not ours. Now, we want to change this.

And we have an interesting situation there. The change is going to have to come from governments. The governments will have to lead. Governments have previously not been leaders in IT. They were in the 1980s, by the way. Governments were the first big users of information systems. But right now, the commercial world is fine with the situation as it is. They run their stuff on AWS. It’s great. It runs on Amazon. It’s great. It runs on Azure. It’s fine. But they’re not going to change because of digital autonomy. Companies are not rewarded for thinking about digital autonomy.

The only people that can think about this stuff are actual governments that have a horizon that stretches beyond the next quarter’s results. So governments will have to lead, which is why our meeting today is so important.

My involvement with this stuff kicked off around five years ago when we were talking about the 5G migration. And people said, are we going to let China run our telecommunications networks? That would be horrible. And when that was going on, I was an actual supplier to these telecommunication networks. And lots of people in the canteen and in the restaurant there were Chinese already.

So we were having a whole discussion about 5G. Should we hand that to the Chinese? But we had already handed everything to the Chinese, but people didn’t want to talk about that. So I could not shut up about this. So I wrote a big rant about this where I said, look, we already do not control our telecommunications networks in Europe.

I am told that Thierry Breton read this piece. It’s a high point in my life. But more importantly, we now have the 5G toolbox and we actually got to work. But this is like ancient history which is now repeating itself on a grander scale, not just 5G, but for all computing systems.

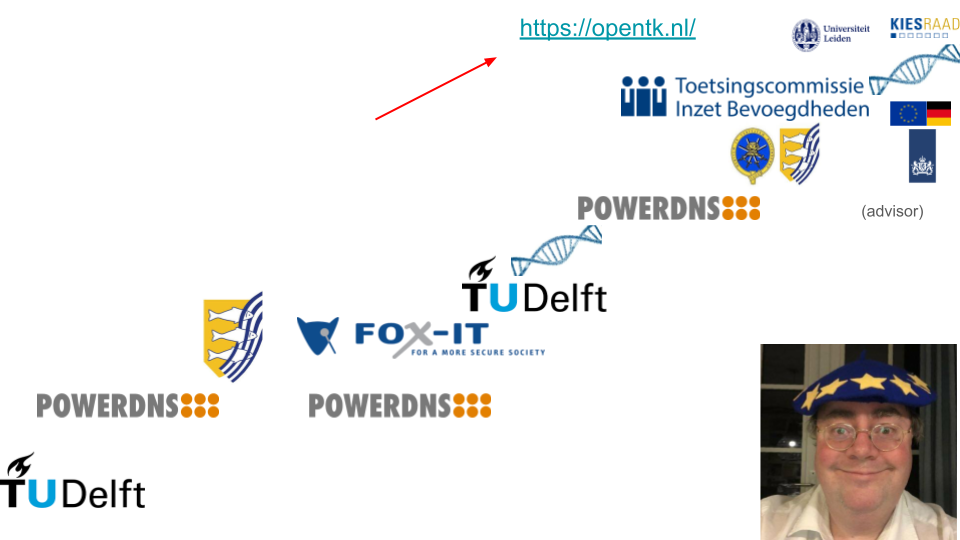

Very briefly about myself, I actually run stuff online. So there are many people that are very involved in digital commons, but they are, charitably said, somewhat removed from practice. I actually run stuff, so this is a website which you can see the Dutch parliament and follow them very closely. It’s quite popular.

PowerDNS is a European company that I co-founded, which does important telecommunication software for like half of the internet in Europe. And I’m no longer affiliated with PowerDNS, but they still run that stuff. So I sort of know what’s going on.

This is my other thing. I wrote a European GPS, Galileo monitoring system because no one was monitoring how well Galileo was working. I didn’t like that, so I built a monitoring system that found all kinds of problems in Galileo.

The European Commission/Galileo were not initially very happy with my finding that out. Now, in an interesting reversal, the European Commission actually relies on my monitoring. But maybe in an interesting comparison to today, the European Commission is really happy with my monitoring, and they allow me to brag about this.

Why is that? Because they have not found any lawful/legal way to support my efforts. So they say, “Lovely that you do this, but we have no mechanism to support your digital commons of your satellite monitoring.” So they support me by allowing me to brag about it, which is actually interesting for today as the EDIC could enable similar bragging about worthwhile projects, which would be good.

And I run all this stuff on my own server at home, and it costs me 500 euros a year. Why do I mention this? There is this widely-held belief in Europe that you can do nothing without big American clouds, whereas I run a parliamentary monitoring system, a satellite monitoring system, and an electricity monitoring system and more on my small computer that sits on my desk. It is possible if you know what you’re doing.

The worldwide technology situation

So this is the worldwide technology situation right now, and it’s not pretty. So you see here all the clouds, they come from the West, and all the hardware and the maintenance comes from the East. And we sit there in the middle as Europeans.

It’s not a happy place to be, because you can wonder, what are we doing in Europe if we get the clouds from here and the maintenance and equipment from there? There are a few things that we are still doing. We have a few things that are still here in Europe:

I would like to mention the beer, the cheese, the chocolate, and the tax structuring. We are very good with tax structuring in the Netherlands.

And this might be a bit depressing if you look at it again, because all these other people have the clouds and the technology, but we have a few things going for us here in Europe.

All the chips that are used in these clouds come from equipment that is being made in Europe. So we have a giant IMEC in Belgium, we have ASML of course, and we have the lasers from a company confusingly called TRUMPF, but they make the very best lasers in the world, and Zeiss makes the very best optics in the world, and this is a European success story.

So we are now worrying about all these clouds being out of our control, but they all come out of our machines. But we’re not the kind of community that says we’re going to not give you our machines anymore. That’s not how we work.

So here is the international cloud world. And it’s not a scientific thing, so don’t measure the actual pixels, but to a large extent, the whole cloud business is Amazon, is Google, is Microsoft. That’s it.

But if you look really carefully under the E from Google, there’s some smudges there, so we’re going to zoom in:

There are some actual European companies. Some of these are actually quite large. So IONOS in Germany does like one and a half billion euros of revenue per year. That’s like real money. But that’s what the other companies do in a day.

So the scale difference between Europe and the US is just not good.

This is news from yesterday:

So already mentioned earlier this morning in some of the very good talks, the International Criminal Court. Yesterday, the US took a step further. They said we want the International Criminal Court to change their statute so that they will rule out ever investigating Donald Trump or his people.

And otherwise, we’ll kick you out of all our clouds and companies. We heard this morning how bad it is when this happens. But this is the kind of world we live in. We’re utterly dependent on the US services, and yeah, we have a few pieces of leverage ourselves, but we’re not using them.

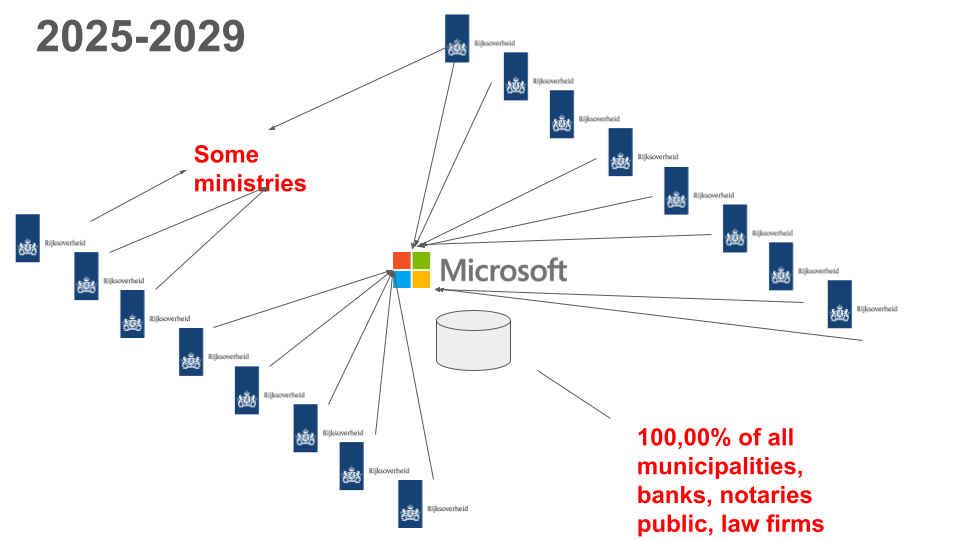

So, just to say how terrible things are. This is a prediction how the Dutch government will email with itself starting 2026:

There are a few brave ministries, and some of them are present here, who are retaining their own on-premise service. That’s glorious news.

(applause)

The problem is all the other parts of the Dutch government.

They are totally dependent on Microsoft. Which means that if the Dutch Ministry of Finance wants to send an email to the tax agency, they will have to do so through America. Which is sort of worrying, because we do have these things that we would not like to share with America on tax details, because we are very good with tax structuring here. So this is a worrying thing.

100% of all cities, municipalities, 100% of banks. I did a talk for the notaries where you sell your house and stuff. 100% Microsoft 365. Which means that if the US turns that off, we are in deep shit. But the presentation gets worse from here.

The reality here now is, do you want to email? Well, you better be nice to the US. Because, if they don’t feel like it, you don’t email.

Now, many people are upset about this. And for the past year or so, sort of by accident, I got invited to all kinds of interesting places to drink coffee. I can now drink large amounts of coffee. And do talks, explain people this stuff.

Getting attention for how bad things are

I’m not actually telling people anything new. I’m just summarizing, saying, look, this is how it is.

This was in Dutch Parliament:

I think Art was also there. And there I complained about our total dependency. But it didn’t help. So I had to escalate.

Together with the Eurostack initiative, I went to the European Commission, Henna Virkkunen, and she also said it was terrible. And then we went to Mr. Séjourné, who also said it was terrible. And it didn’t work. But it was nice to say this. I have to admit, they listened really well, and asked really good questions.

But this escalation continued. So I went to the Dutch king, and I told him it was no good. And you can tell he’s the king, because all of us have a nametag. But he doesn’t. He’s the king:

Anyhow, this was a very useful meeting. I cannot complain that people are not listening. They are definitely listening. But that also didn’t help. So we escalated to Dutch TV. This is one of the most popular Dutch TV programs:

They did a 23-minute item on this. It’s on YouTube. It has subtitles by now. And if you want a 23-minute explanation of how deep the shit we are in, this is a very accessible video.

But this also did not help. But I have one last hope that we can finally solve this problem , and that would be you:

(loud applause)

I’m really hopeful, even if I may have some critical notes later today, but please see this as my uncle role, my supportive critical uncle role.

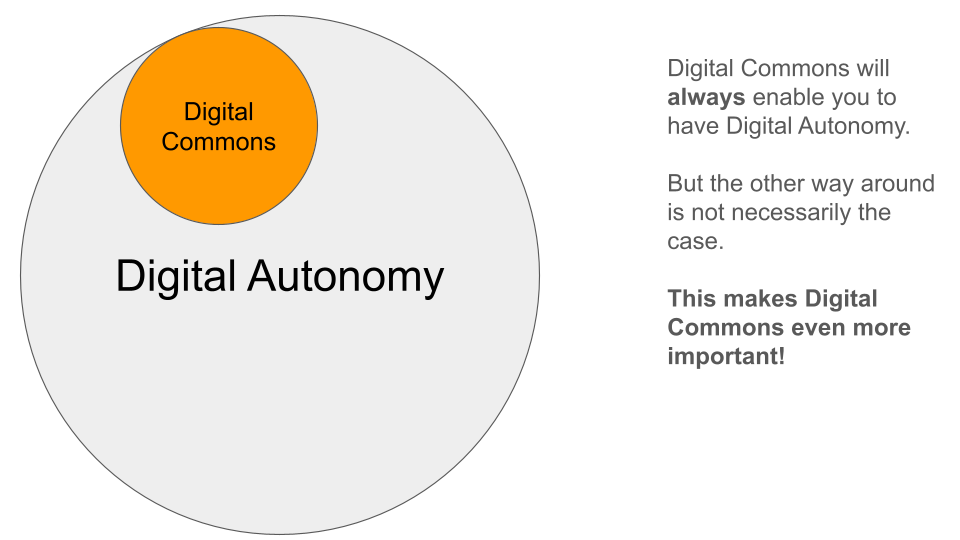

So now we’re making a little bridge between digital autonomy and digital commons, because these are not the same thing. And it is important to realize that if you have a digital commons, and we’ll come to the tricky business of defining what a digital commons is, but we do know that if you have a digital common, you have digital sovereignty, because then you can run your own stuff.

But the other way around is not the case. So let’s say you could copy-paste Amazon to Europe. And we make a new Amazon, but now owned by Deutsche Telekom, something like that. We would not have a digital commons. We would still have to know that whatever we do, Deutsche Telekom or whoever would have to agree with that. So it’s not enough to just copy-paste what they have in the US. We actually want something different.

And I’m zooming in on that a little bit.

Outrageous US/big tech involvement in our government communications

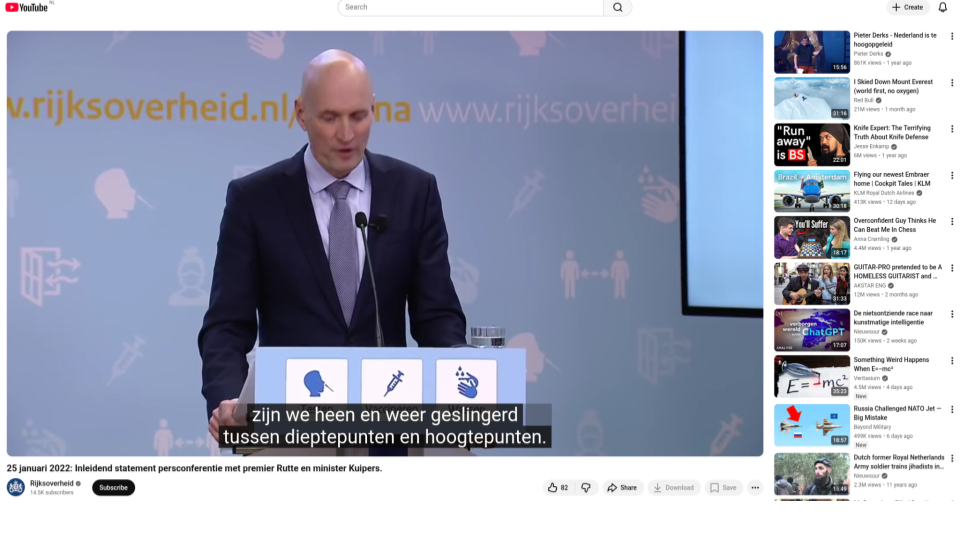

So this is the Dutch government doing a COVID-19 press conference. You can see the signs, wash your hands and stuff:

And European governments, and I have an example from the Dutch government because I know them reasonably well, but European governments and the European Space Agency and ArianeSpace etc, they broadcast their press conferences on YouTube. Which is, by now, crazy stuff.

Because here you have a COVID press conference and on the right we have all the weird advertising that comes with that. This is not the best stuff. So we are fighting an information war with Russia. And what we are doing here is telling people, this is our official COVID press conference and look at this conspiracy stuff on Russian jet fighters and NATO.

And then I watched another presentation. You know, when you’re done watching a presentation, YouTube proposes other videos for you to watch. And it came up with this:

I get a Dutch minister telling me about COVID, and then I get this.

Why do I show this stuff?

What I mean by this is not only do we rely on the US technology for everything, we have also culturally accepted it as completely normal that they take our government communications and add this garbage to it. And that’s actually unacceptable.

What you would like to have is a COVID-19 presentation, and then after the end of the presentation, there are five other educational videos to watch about vaccination and health and stuff, and not this guy.

X, I don’t have to tell you about X (Twitter), I don’t know why people are on there, but in many places it’s an official government communication channel. So cities will say, well, there’s a power outage and we’re telling you over X. That is not a good place to be. It’s not a good government communication channel.

And I understand that for political reasons, some people would like to reach right-wing voters, I get that, but as government communication, it sucks:

Well, it gets a little bit worse. In the Netherlands, there’s a spy agency, I worked there, I like them, but they, for some reason, for multiple years, maybe 14 years, whenever someone applied for a job at the intelligence agency, we would immediately share that news with Google.

There were all kinds of technical excuses, that we don’t actually share the cookies, and we’re only sending the IP address, but it turns out, in the Netherlands, if you have an IP address from the internet connection, you keep it for five years. Which means that we were effectively telling the Americans whoever was applying for a job at the intelligence agency.

They now quit doing it:

So again, wonderful news, but we apparently found this acceptable.

Which is ridiculous, but they said you can just share that stuff with the Americans, for 14 years. So this is the cultural aspect of digital autonomy, and this is the thing that if you have digital commons, you would be able to say, I can communicate with my citizens, and only we and the citizens know. You don’t have to tell everyone else.

This is another example, again, these are fine people, the Dutch data protection authority, they keep on adding cookies to their stuff, and tracking people:

They keep on violating their own rules. Why does that happen? Not because they’re stupid people. They’re nice people. But the world is now so saturated with American tracking and cookies, that it becomes exceptionally difficult to do something else.

So, for example, I write a newsletter. And I found out that it was so tricky to guarantee that there were no cookies and trackers in that newsletter, that being the idiot that I am, I wrote my own newsletter software. Because it was easier to do it that way. So, we are in really deep, deep shit.

So, as a summary, our most basic communications abilities are now only provided through US platforms. So, as a European government, if you want to reach your citizens, you have to do it through the US. Through a US that tells us that they want to dismantle the EU and that they hate us. It does not seem like a good choice. Maybe it used to be a decent choice. I mean, I get that. It has to work.

But it’s not such a great choice right now. And actually, these basic things, we should have a clear channel of communication where the government can say, this is what we think, and do view or read it, and not get these YouTube advertisements added to it.

What is a digital commons?

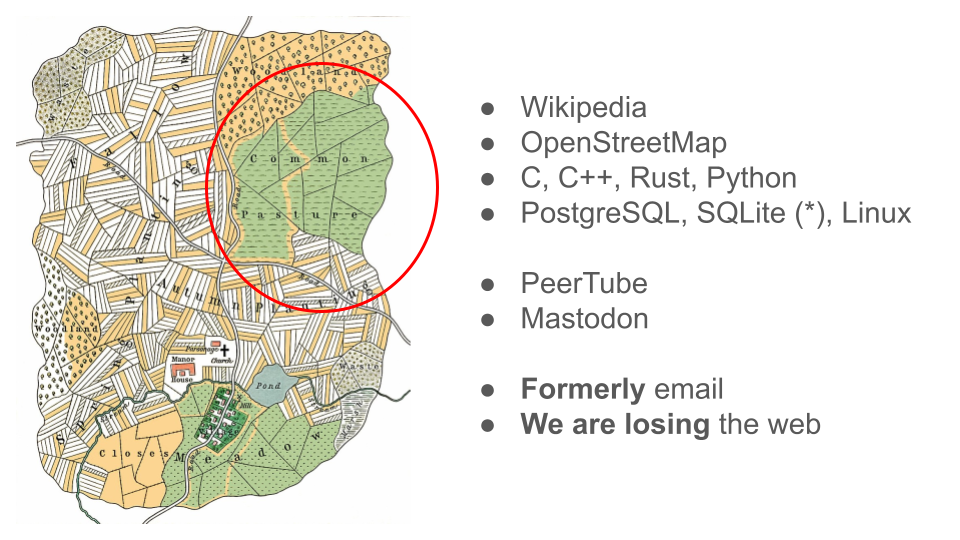

Now we get to the tricky point. What are these digital commons? Well, we heard this morning from the minister that it was this field where everyone could let their sheep graze and stuff, and that’s in the circle right, labeled commons, pasture:

I think they also had fights over that and who could put on their sheep there first. So it’s not that easy. But if you want to say, what is a digital commons, you have a far harder time. There are very academic definitions that do not quite help us.

I put up a few very, very technical digital commons. Linux, the PostgreSQL database, the SQLite database. Wikipedia, I think we can all agree that these are common resources that are amazing.

If the world would end we would only have to store a copy of Wikipedia and that has all our knowledge. This is amazing stuff. OpenStreetMap, if there is a yak path somewhere in Mongolia, it is on OpenStreetMap. And I mention OpenStreetMap specifically because it has use for governments. Governments share cartographic data all the time on their websites.

OpenStreetMap is there for us and we [governments] are only using it sparingly. Many government sites have Google Maps on them, which again means that you get these McDonald’s advertisements on your government stuff, if you don’t pay very close attention.

I want to mention PeerTube and Mastodon. We put everything on YouTube right now and there are good reasons why people do that. I understand why people stream their press conference on YouTube. But we now also have a project called PeerTube, which was started like 15 years ago by a hacker called Chocobozz. I’m not sure if we know his real name by now.

But this is a platform on which, with some investment, we could do all these broadcasts as well and not have to rely on YouTube. It’s not going to be easy, but it’s possible.

Mastodon is the Twitter workalike without the celebrities. But if, as a government, you would say, I want to share short messages with people, that would be the place to do it. Because everyone can always join in. You’re not kicked out if Elon doesn’t like you. And you can even send messages there that you don’t like Elon.

These are things that are quite clearly where you can say, yeah, this is digital and it is a commons. Because everyone can use it, everyone can take part. These are the things that we like.

I mentioned email. I said it’s a former digital commons. Now, there are a few things to say about that. Why is it no longer a digital commons?

False digital commons

First, I briefly want to talk about these perceived false digital commons. This is what real people use in the world. Real people know Google Docs is infrastructure for everyone. They will organize their birthday parties there. They will launch their school projects on it. They will do everything on Google Docs. And it is entirely free and it never gets in your way.

We know that this is not an actual digital commons because once you try to write stuff there that they don’t agree with in the US, it stops working. But for most people, this is a perfect digital commons. As is YouTube. If you have a conference, you can upload your 20 talks on YouTube. YouTube will not complain. It is there for you. It is your infrastructure.

The same goes for other things, Discord. ChatGPT is considered by normal people to be a free infrastructure that can be used for everything. Of course, we know that it’s all terrible and not a commons. But you have to realize in the real world, people say that these are the things that we build on.

If we want to make any headway, we should also have things like this that are not evil. A Eutube if you will.

Ok, email. Email was a digital commons. Anyone could set up a mail server and send mail. Anyone could set up a mail server and receive email. You did not have to ask permission from anyone. Anyone could send email and it would work. It was lovely. But it no longer works like that. But most of you probably do not experience any problem today.

Google, Microsoft, Apple have said we will accept maybe 95% of email outside our world, and we will randomly discard the rest unless you are one of the big three or big four [email providers]. So anyone that tries to independently send email right now discovers that quite often it will not arrive.

And why will it not arrive? Well the people from Microsoft and I had an interaction a few months ago. They say things like “Yeah, we thought all your emails were spam so we just blocked your server.” And you go like, “I’m trying to send an important email to people. I’ve never sent any spam.” And they go like, “We also did not receive this message because we also think that this is spam.”

So you have no real way of interacting with these gatekeepers. Right now if you would say, “I want to be an independent European email provider.” You have to be honest to your users and tell them you’re going to lose out on 5% of your email [deliveries].

And that’s pretty sad. We have lost email as a digital commons. This is not something that anyone can join in anymore. You need permission from the American companies. That’s terrible. I hope that we can address it.

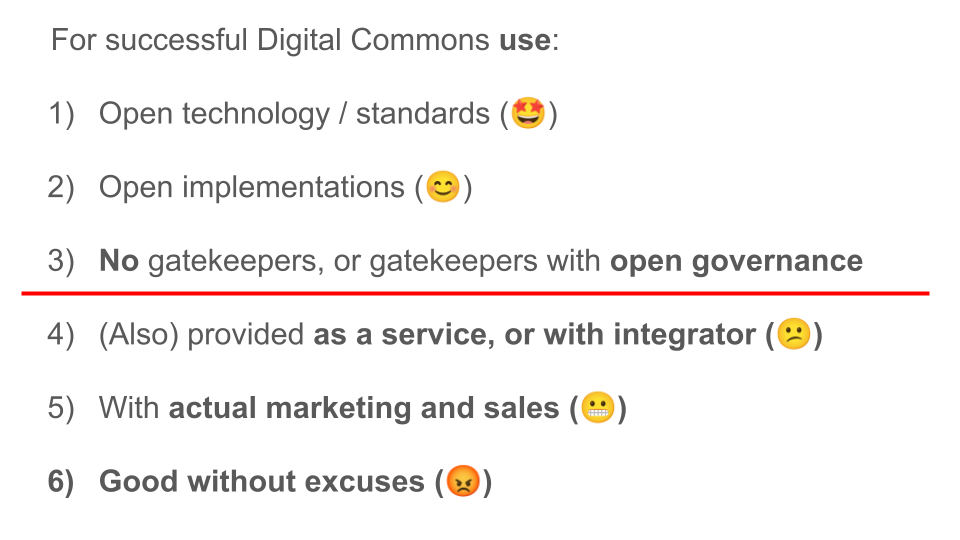

The six requirements for successful digital commons use

In our world of free software, digital commons, there is a lot of focus from the technical people and I am a very big nerd, so I count myself among the technical people. We have good standards, we should work on good standards, and we should work on good software that implements those standards and we should also in many cases have governance like the Wikipedia has governance that people spend a lot of time on. OpenStreetMap has whole conferences to decide what to do.

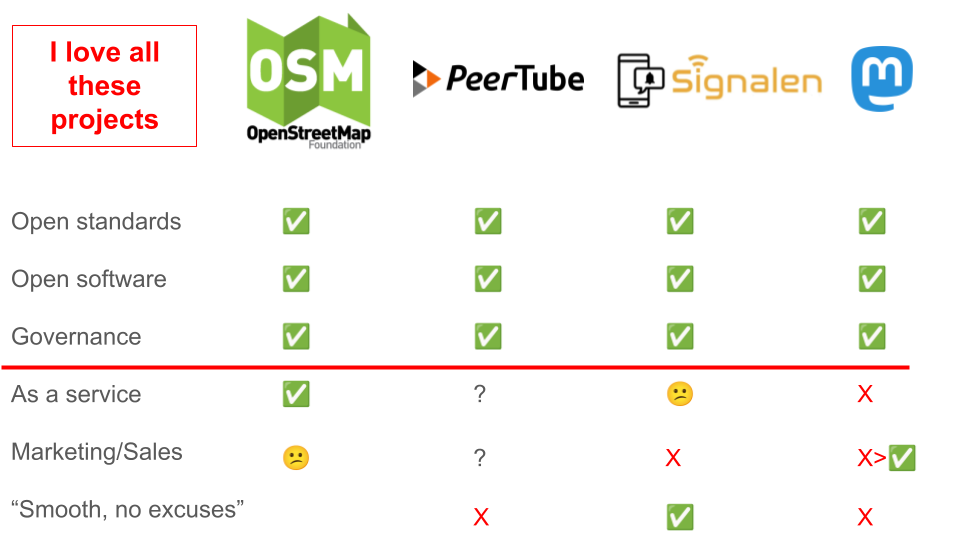

These first three things are very obvious to the digital commons community which has been around for many years:

But if we want to be actually successful there are three more things that need to happen. And these are often neglected and I hope that we can have a role here [as an EDIC].

Governments and big companies do not use technology right now. It sounds weird but the government wants to get their stuff “as a service”. So they say I want to run a newsletter for my citizens, but we are not going to install any newsletter software we want someone else to do that for us. As technical people we think that this is wrong we think that important entities like governments should run their own crucial software and control that.

The governments do not agree. So if we want to make any headway, anything we do this has to be more than just good technology, good software and good governance.

It has also convincingly to be supplied as a service, so that people can use it.

Secondly, and we often forget about that: actual marketing and sales. These sound like very dirty words in the digital commons context. Now many people have found that even if you have great software and it is freely available, that people will not automatically use it. Because even if the software is free it takes convincing to change people’s behaviour and choices.

And as a very simple example for that, many of us use WhatsApp and the smarter people also use Signal.

If you try to convince your friends to also install Signal, they often say no, I’m not going to do it. It’s too much work. Whereas signal is also free and it works exactly the same way. The only thing you have to change is that I now use the blue round thing instead of the green round thing to chat. Still people say no, I’m not going to do it.

The role of marketing and sales is to help people deal with this change. That means that even if we come up with the best alternative for Microsoft 365 that is out there, it will not sell itself. It will need advocacy. It will need evangelism to make it happen. This is part of the whole stack.

The third and final part is not coming up with any usability excuses. I wrote a whole piece on it. I love the open source people and I’m an open source person. But there are no excuses. If your software is a bit weird, people will not use it. If signing on to your Mastodon message service is a bit difficult people will not do it.

If you want to move people to our Glorious digital commons platforms, we cannot make it any more difficult than it has to be. And you need to fix this first before you work on all the other things, because if you say well we have a better email system and but you need to sign on with this weird program, it’s not going to work.

So this means having usability experts. And this means not saying yeah, yeah, once you get it, it is easy. No, it’s not good enough. So I want to stress this, in whatever we endeavor with our digital commons. Actually have usability people try it and get your friends on it. Your normal friends. (I mean this in the best way).

So I list a few favorite digital commons projects and here you can already see the pain of open source software! Because my whole table is now messed up!

Correct version of the table

In the actual presentation, this table was messed up!

I did not plan this but this is a great example of what I just said. If you use software that is slightly different, people will say, in my presentation I used your nice European office stuff and now my presentation was messed up. Never again!

I know you’ll see through this messed up table, but in this I looked at various current digital commons projects and see how well they are doing. I’m going to focus on the Signalen App. 30% of Dutch citizens can report a broken sign or a broken street light using the Signalen App and it’s great. It works tremendously well, 30% of Dutch people are serviced by it and it’s wonderful.

The issue is however, it is still only 30%. Even though this software is free and does everything you want. Why are not more cities using the Signalen App? Because we don’t have the time to do the evangelism and tell them that they should do it. So currently many cities are actually spending money on this with commercial suppliers, even though the free Signalen App is just fine.

So that’s a great example where you say well, it’s not enough to have the great open source software and standards. It needs a little bit more. It needs marketing and sales.

OpenStreetMap is another interesting case. Almost all government use of Google Maps could stop like today. You can easily replace Google Maps by an OpenStreetMap implementation and still people are like, yeah we like our Google maps, we’ll pay for them.

As an example the Dutch Ministry of General Affairs, where the Prime Minister lives, they have an OpenStreetMap solution available that any government website can use and still many of them are like yeah, but I prefer my McDonald’s advertisements on Google Maps. So that is again an example where it is not good enough to have good technology. We need more. We need good marketing, “sales”, good governance, but also great “as a service” implementations, and stuff that works without excuses, just like people expect.

What does the EDIC want?

Moving on, this is the part where I have a bit of a whiplash and am a bit confused. I investigated, what are the goals of the DC EDIC and this is what is on the website:

And this is sort of good stuff. I mean nothing here is bad. It’s like you’re going to coordinate, you’re gonna bring people together. We’re gonna facilitate things and funding. We’re gonna have a hub and we’re gonna hand out an award. I like that one. It’s one of the key goals.

But this is different than what I heard this morning during this meeting. This morning I heard rousing speeches and they were really good on how we’re gonna replace Microsoft 365 in 12 different ways and we’re gonna win the battle against the Americans and it’s good stuff. I’m really all on board with that.

This morning I was misquoted in Dutch news where I said this EDIC will be a talking shop. And what I actually said this EDIC risks becoming a talking shop. I think if we’re honest that is a risk because it has happened before. I can talk about Gaia-X if you want! This is a risk that we should be careful about.

But this is what is on the site as our goals, whereas I think our goals are far bigger than that.

When I made this presentation, I believed the website so I only have some modest suggestions to go with these modest goals.

I think if we want to be super ambitious, that is also great, but let us then also put it on the website. Because if an outsider sees this, he’s like, oh, it’s a EU thing. Oh, they’re gonna hand out an award. They did not say we’re gonna remove Donald Trump from our digital ecosystem. So it would be good to have that up there. So don’t get me wrong, I’m very much in favor of doing the wild thing, but I have some modest suggestions that maybe could be done before we attempt to kill the Trump digital hegemony.

Suggestions

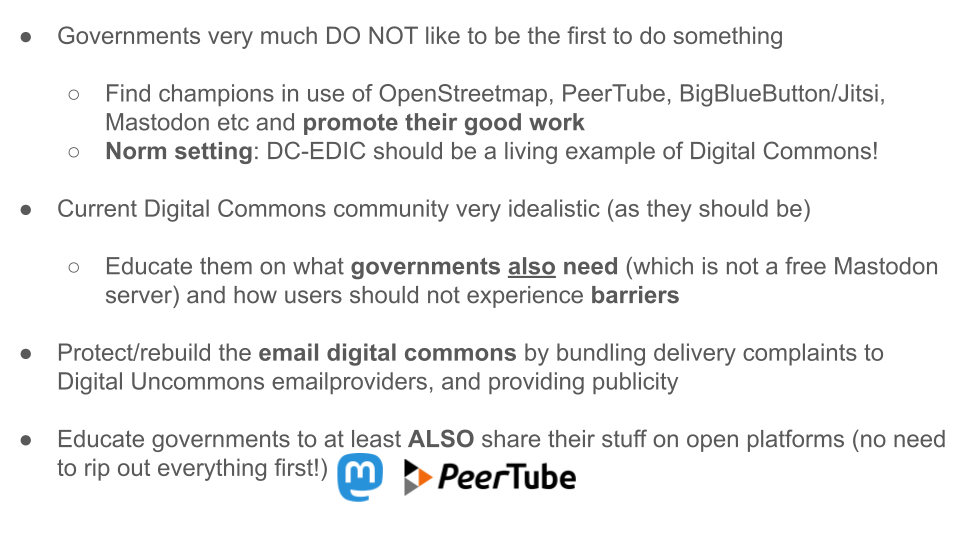

On the coordinating role. Governments do not want to be first in anything. So if you tell a government, do you want to be the first one to have this PeerTube thing for your press conference? They’re gonna be like, hell no! Because it might go wrong.

And the thing is, within most large organizations, including governments, having something fail is not good for you. There’s no reward for being brave in government. Well, only if it worked out. I mean, if it’s worth it and it worked, everyone is happy.

But if you say, hey, we took a chance and we also used this open source presentation software and now the minister’s presentation is messed up like mine was just now, that was sort of the last time anyone did that.

One of the key things that this EDIC can do is say, look, is there a nice project that is successful already in one of the 27 member states? And highlight that. Luxembourg did this thing, it worked really well. Here’s an interview with the people that did it. And here’s a rousing quote from the minister who said that he likes it. That’s worth its weight in gold! Because governments and other large organizations, if they see that someone else has done it already, and it worked, they’re like, okay, then we can do it as well.

The EDIC is a great place for gathering these great stories and also motivating these people to be proud and share the good news. And I think it’s a great opportunity for people like Germany, Schleswig-Holstein. They had their famous move away from Microsoft. They went to Brussels to tell everyone about it. They had a whole evening with food and drinks. It was lovely. This is the sort of thing that moves the needle in places.

Because people say, okay, if Schleswig-Holstein can make it work, then we can make it work as well. Especially if Schleswig-Holstein says, we’re going to tell you how to do it. Which they are willing to do, by the way.

Norm setting. The EDIC itself is an example entity. So, if the EDIC does a movie I do not want to see that movie [only] on YouTube. If the EDIC decides to do short messaging, I want them to also come to Mastodon. Because that is where all the digital commons people are. And you can also go to other governments and say, why are you organizing your digital commons event via Office Forms? And the problem is, this requires real work. It is very easy to say, hey, we’re organizing all our conferences using Office Forms. And we’re not going to do it any different now.

But you look like a fool if you organize a digital commons conference and you say well first you have to report to Microsoft!

So, be a good example. Even though you don’t have to be completely autonomous and digitally common by the way. So, I can tell you I made this presentation in Google Docs, which is why it looks like shit now on LibreOffice. So it doesn’t mean that everything has to be like perfect open source to please the ideologues.

But try to show and tell. That we look at the website and find that it’s not hosted with Azure. Just show it. Because if you do not show that, you become a counter example. That even the digital commons EDIC people put all their stuff on YouTube and US clouds, so why should we bother? Please be a good example.

Understanding our users & audience

On the idealistic side, there are many of these open source developers like me who are blinded by technical greatness. If I see something that’s technically great, I’m like, yes. But we should be informed that governments look for other things than optimal bit placement in data structures. They do not care about that.

The government wants to say, we did this and it worked and it was a success and the minister could come there and cut the ribbon and it was wonderful. So there is also an educational aspect that we go to the digital commons enthusiasts and say, have you thought about how people use this?

And I want to give you one great example, which is a sad example. Actual offices use Microsoft Word for the craziest of things. And one of the sort of relatively normal things is mail merge. Where you template one letter and have to print it out for 200 addresses, with labels. This still actually happens. Then people who build an open source web based text editing environment and say, hey, our text editing environment is perfect, does everything you need. And then someone asks, do you also do mail merge?

And you say, no, you should not do that anymore anyhow. No one needs that anymore!. And then you’re telling that to the people that DO need that. So an important message to ideology-driven people is also really, really, really talk to and listen to the customers, the users that you want to serve.

And do not just build your own perfect solution that you personally like. So this is not an easy conversation to have because the open source people are super happy that they built this font engine that renders the fonts in the very best way. And the important question is, do you also do mail merge?

So I think the EDIC could have a role in educating governments, but also educating people like me that like to focus on pixels.

Protecting the email digital commons

Protect and rebuild the email digital commons. Now this is actually key. If you are a government and you want to send out tax notices via email, and you discover that your tax notices are not always arriving, and then someone says, well, the solution is that we send the tax notices via Amazon or via Microsoft, then people will do that. They will say, okay, you’re forced to do this, otherwise our email does not arrive, so we are now sending our email via Amazon.

It is likely that this “spam” filtering being performed by the big American companies is already illegal under the European law, because we have a whole zoo of acts on this, and we also have generic telecommunication law, which also says things about, can you just block people’s communications and not offer them any explanation or recourse?

One key thing that we could do is reopen the email digital commons. How does that work? If you hear from a government that they are unable to send their own email anymore because it does not arrive, and that they therefore are pondering shifting to Microsoft, no, we’re not going to do that. We’re going to start a lawsuit. We’re going to tell people it’s not good that you throw away legitimate email from European governments, and we’re going to make this hurt.

The interesting thing is, no one has done this so far. As I told you, Microsoft recently blocked all my email. I’m visible enough that I could make noise about that. They said, oh, we’re going to fix it. And they quickly did. They did not say sorry, by the way. They still blamed me, which is difficult to explain, but they said, yeah, it’s your fault that we blocked your email.

But this is a key thing for a digital commons, and it would be relatively easy to start doing this kind of thing from a legal perspective and remind people that it’s not good to just throw away email that does not come from an American big tech company.

Also be on open platforms

Also, educate governments to at least also share their stuff on open platforms. So people say we’re not switching to this open platform because we have so much fun on Twitter. Well, people can stay on Twitter if they want, fine, but at least post your messages also somewhere else.

Because this lends a lot of credibility to these non-American platforms. Now, the interesting thing is, quite a number of governments have gone to alternative platforms and also have gone away again. Why did it happen? Someone in marketing said, yeah, this is too much work. I have to click twice now. And so what happened is that a marketing department has now made a policy choice [to fully rely on X], and the marketing department is not the place where such strategic decisions should happen.

Many people try to get their governments to leave X, okay, and you could do that, but I would far more prefer that they tell governments, fine, be on X, but also be somewhere else, so that if you have an important message to your people, that they can also access it if X has issues with the message (or with you).

This goes for X, this goes also for YouTube. Live by example. Let governments be an example that you can (also) be somewhere else.

You won’t believe how attached people are to Excel sheets

Now, this is my final message, well, for this presentation, at least. I heard a lot of talk today about the text editors and the word processors. With my previous company, PowerDNS, we were part of the German company Open-Xchange, which also makes a productivity suite, which is open source.

You will not believe how attached people are to Excel. I used to say no one loves Outlook, but then people came to me and said, yeah, I do love Outlook. Because people have been using it for 25 years, and they now have three-weekly alternating agenda meetings that automatically know which room is available etc. It’s amazing what people can do with it.

If you try to displace the Microsoft office suite, it is the most difficult thing you can do. There was a study that said, yeah, Word has like 2,000 features, and probably only 100 of these features ever get used. And it turns out that is not the case. Each individual user uses only maybe 100 features, but once you have 200 people in a company, all features end up getting used by someone.

Because there’s always someone that does the double-sided upside-down printing. I want to warn you. Many people have attempted to come at the king, which is Microsoft 365, and failed because there were legitimate needs from people that said, we do all our tax calculations with Excel, which is horrible. Yet this is what people do.

And then you come around and replace their Excel, and then you get a table that doesn’t work anymore. And then they hate you forever.

So I want to warn you, you only have one chance to do this. So let’s say you go to a government department and say, we’re going to switch to the glorious LaSuite or OpenDesk or MijnBureau. And by the way, I very much appreciate those efforts, and my friends are working on it, so don’t get me wrong. I’m saying this is wonderful stuff.

But if you disappoint a department, even only once, they’re going to be like, we’re not giving you a second chance for the next five years. So if you come up with a solution and say, we’re going to just migrate all of you, and it doesn’t work, you have ruined it.

So I honestly wish everyone the best of luck with these new programs and the tech process and things, but work them in really smoothly. And look at Schleswig-Holstein, where even they, after a few years of preparation, said we’re initially going to move only 70% of our people.

Because we identified that 30% are power users that we are going to disappoint when we do that. So I love the enthusiasm, but “if you come at the king, you had best not miss”.

Wrapping up

So I think we are sort of reaching the end here. Digital commons is a bigger call than digital autonomy. It’s a better call because digital commons gets you digital autonomy, but not always the other way around.

Almost everything we do today is Digitally Uncommon. So the governments put their pandemic announcements next to the anti-vax and conspiracy movies, which is kind of strange.

We are so embedded with the US ecosystem that even privacy authorities fail to send out email without trackers, even though they want to do a good job. The ecosystem is so poisoned that they don’t manage to do it.

So we’re in a really bad place. We have lots of technical people that are very motivated to innovate technically, but it’s not enough to have the good technology, and the good software, and the good governance. We also need to have sales, the marketing. We need to have a very good as-a-service, and we need to make sure that there are no excuses needed, the tech needs to be smooth.

People will not like your stuff because it is European. They will even dislike it actually, because it is change. So you have to be better than what they are used to.

I think you are a wonderful place to address these issues, to educate governments, educate developers, to get an ecosystem going. If you are a PeerTube as a service provider, would you like to stream our first press conference? And get that together and make it work well. The EDIC in that way could invite people and give people an excuse to do it, because hey the EU is doing it, we’re going to join in. Which provides reassurance.

Also identify the good things member state governments are doing and highlight them. Other member states will follow those examples.

We’re super ambitious, and I want that [replacing Microsoft 365] to work, but meanwhile it is good to look at the more modest goals I outlined earlier - outreach, education, even as we are preparing to take over the world.

I want to end this talk with a quote. I mentioned the C++ language, which was invented by a Danish programmer, Bjarne Stroustrup, and he began his book on C++ with a lovely quote.

“In every new beginning, there is magic”, and I wish you some of that magic as well for the EDIC Digital Commons.

Thank you.

Further reading

- My digital autonomy/cloud overview

- Art de Blaauw’s summary of the day (CIO central Dutch government, chair DC EDIC)

- Adriana Groh’s summary (CEO of the German Sovereign Tech Agency)

- Bert Boerland’s summary (Senior Government sales executive, SUSE)

- Timo Bravo Rebolledo’s reflection (Dutch Government Senior Advisor Digital Affairs)

- Digital Commons EDIC launches to advance Europe’s technological sovereignty