Useful Spy Books

Reading a good book is a great joy. And recommending a good book is almost as enjoyable.

I’ve long been fascinated by books on espionage, and this contributed in no small part to me eventually joining the Dutch intelligence world, and later, rejoining it in some fashion.

If you have favorite books that should be on this page, please let me know on bert@hubertnet.nl! I’m especially looking for books written from different perspectives. Also, since recent developments, I’d like to replace all links to Amazon with links to more generic pages about the books. If you can dig up better links, do send them on!

Even people who have worked on the inside for many years often lack the bigger picture of just what they joined. “Need to know” means that random curiosity is not encouraged, even though there is a lot that is “nice to know” or even “good to know”.

A broader understanding of things can be very helpful, for example when we ponder if the money spent on intelligence agencies might not be better spent elsewhere. Or why everything has to be so secretive. Furthermore, we’d like to have a reasoned opinion of when the inherent violation of trust and privacy by agencies is actually worth it.

Although these are uncomfortable questions, we should not shy away from thinking about them.

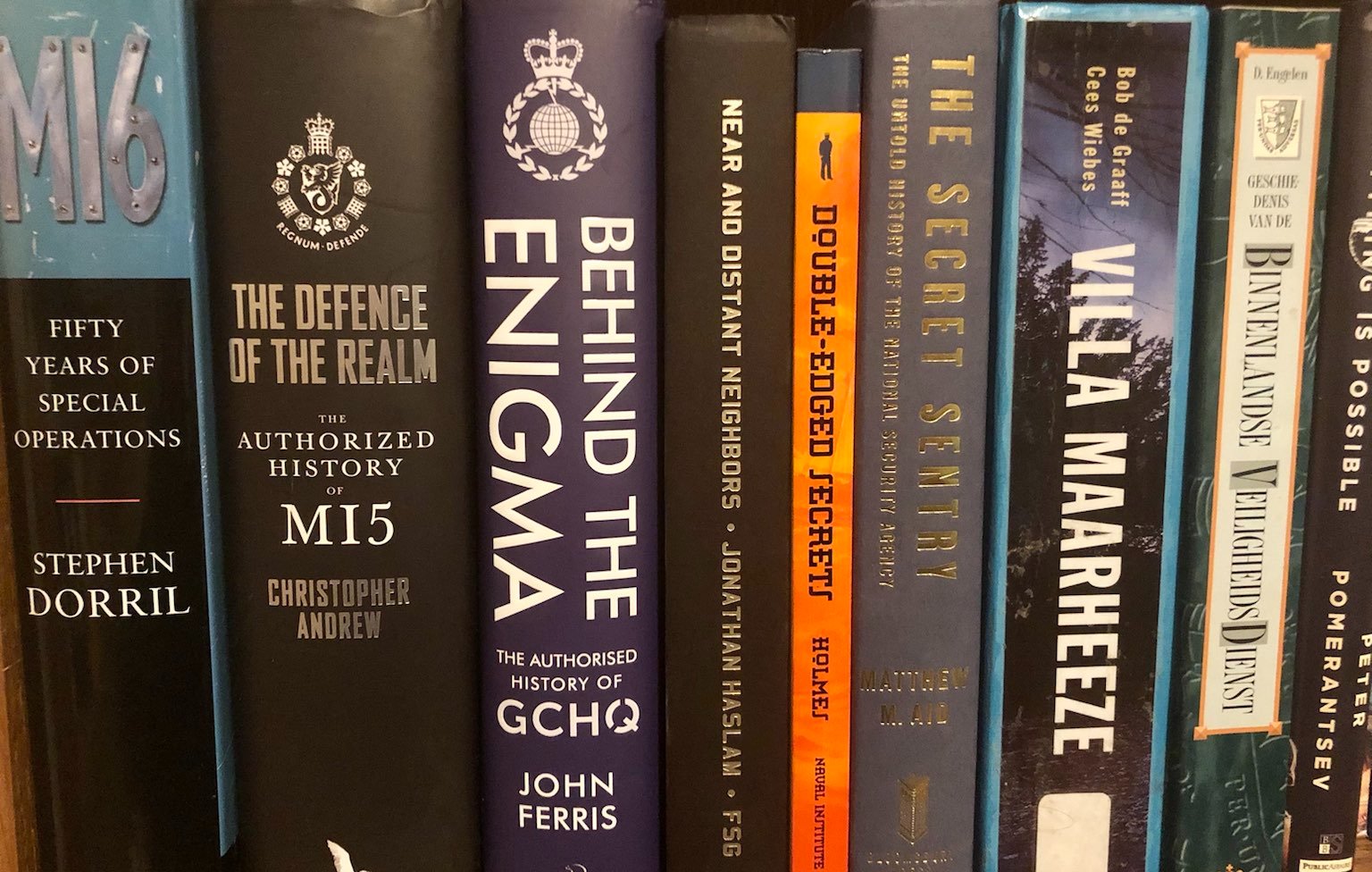

One way for both insiders and outsiders to gain a fuller understanding of intelligence and security agencies is to read books. I am particularly fond of compelling works that at least claim to be true. These are much more readable than the many official or authorized histories that agencies publish about themselves. I’ve yet to finish any of these typically massive books (BVD/AIVD, MI5, MI6, GCHQ).

In addition, almost everything by John le Carré is worth reading. Although his works are most definitely fiction, they paint a literary picture of the world of espionage that, like the best paintings, exposes the nature of reality much better than the real thing.

Other books on this page claim to be factual, but often won’t fully be. Some of these books have gone through checks by intelligence agencies to see if nothing classified is in there. Sometimes authors claim only a few sentences were changed.

The writers however knew their books would be vetted, so it is foreseeable they left out material they knew would upset their national security agencies.

Particularly defectors have a strong incentive to describe what happened to them in a favourable light, or to caricature their former employer. Other authors depended on official archives for their works. These too might paint a one-sided picture.

I do think however that a lot of useful things can be learned from the books below, even though many of them describe events from decades ago. But, some things never change.

One thing I do promise you: all these books are extremely entertaining reads!

Tower of Secrets: A Real Life Spy Thriller

Amazon. Written by Victor Sheymov, a Russian defector.

Sheymov worked for the KGB, with responsibilities for their cipher communications. Eventually he grew frustrated with communism and in 1980 he managed to defect to the US, taking his family with him.

The opening chapters already paint an extremely interesting picture of KGB information and physical security practices. The book also unveils several acoustic & electrical spying techniques that we don’t hear much about today.

Sheymov also documents the lengths the Russian intelligence and security services went through to surveil foreigners but also their own population. It is instructive to ponder what similarly endowed efforts might look like today.

Besides being useful, this book is also a very exciting read.

The Billion Dollar Spy: A True Story of Cold War Espionage and Betrayal

Amazon. Written by David E. Hoffman, an American writer and journalist.

Adolf Tolkachev was a Russian engineer working at the Soviet Radar Design Bureau “Phazotron”.

Tolkachev claims to have become disillusioned with the Soviet Union because of how it had treated his wife’s parents.

Starting in 1977 Tolkachev attempted to approach Americans in order to leak material to them. This initially did not work out, but eventually contact was established, and Adolf Tolkachev delivered mountains of information on Russian radar research, purportedly saving the US a lot of money and time.

This book was written with access to selected CIA cables from this era. It paints a very interesting picture of how to deal with a possible ‘dangle’, an attempt by a foreign intelligence agency to get you to burn resources on a fake informer.

Part of this tale is corroborated by “The Spy in the Moscow Station” described below.

Agent Sonya: Moscow’s Most Daring Wartime Spy

Amazon. By Ben Macintyre.

We should all treasure Ben Macintyre. I can only imagine how much time he must have spent wading through archives, hunting for sufficient detail to write semi-fictional but hopefully factual stories.

Agent Sonya is a recent book, and it is extremely interesting because Ursula Kuczynski was a German communist working for Russia, living through very interesting times in Germany, China, Switzerland and the UK.

Most of the books on this page cover somewhat more recent material, but Agent Sonya is still a mandatory read because of its completely different perspective, describing a Russian female spy working in the west (and China).

Agent Sonya was successful in recruiting agents with access to atomic bomb research, and was active until 1950 when she moved to East Germany.

I can recommend this book highly if only to balance out all the stories on the successes of western agencies.

The Widow Spy

Amazon. By Martha Peterson.

A book that deserves more attention. Martha Peterson was stationed in Laos with her husband who worked for the CIA. He was killed during a secret operation which had to be sold at home as a ‘helicopter incident’. Martha had meanwhile performed some menial work in Laos for the agency as a CIA spouse. Having a master’s degree was of no meaning there, agency wives could only do secretarial work.

After her return to the US she thought her degree, agency work and proven abilities to live in a war zone would help her secure a CIA job. Yet, on the first attempt she again only got offered administrative work. Eventually however she manages to join a career trainee program, after which she learns Russian, and in 1975 gets to be the very first trained female CIA case officer in Moscow.

During her time there, the KGB appears to flat out ignore her, likely because they could not imagine a female officer on the streets. This ignorance made it possible for her to do some daring operations. Specifically, she was heavily involved with getting materials to/from agent TRIGON.

The book is very down to earth and describes many practical aspects of running an agent in Moscow under extremely heavy surveillance. She also describes being detained by the KGB. The stories in ‘The Widow Spy’ line up well with many of the other books on this page, and some of the details are fascinating – like gear used to spot the KGB radio frequencies, or the problems of trying to have a social life while having to hide your CIA role even from your embassy coworkers.

A particularly poignant moment is when she returns to the US and gets to present to FBI counter-intelligence officers, who can not believe the KGB never caught on to her. The FBI people are convinced she just missed the signs of surveillance. Martha tells us that she then asked how many female KGB officers the FBI performed surveillance on, a question they preferred not to answer.

All in all a recommended book for a slightly different view of spying work.

Spycatcher: The Candid Autobiography of a Senior Intelligence Officer

Wikipedia. By Peter Wright and Paul Greengrass.

Peter Wright worked with and for UK intelligence and security services for over 30 years. When ‘Spycatcher’ appeared in 1985 it caused an enormous uproar and led to many many lawsuits and gag orders for the English press. Oddly these orders did not extend to Scotland. Millions of copies were sold.

Wright & Greengrass wrote a very compelling book in which they leaked tons of things that had no need to be leaked. There are some echoes of Edward Snowden here. In addition however, this book shed a much needed light on things that very much did deserve far wider attention. And unlike Snowden’s work, Wright does provide a lot of intelligence context and insight. Wright’s career spanned the gamut from scientist to very senior officer.

Wright had a big ax to grind when he left – for reasons I don’t understand, UK intelligence workers very often had dire pension arrangements. Due to a technicality, the pension Wright had accrued for earlier government work was denied to him.

In addition, Wright was convinced that Roger Hollis, eventually Director General of MI5, was in fact a spy. While there had been very serious reasons to think so, in the end the allegations were not substantiated, or at least not to the extent that anything was done with them.

‘Spycatcher’ is extremely informative on many technical operations. It also sheds a valuable light on many intelligence dilemmas and paradoxes that are very much alive today.

One is what I would like to call the communication triangle. Communications can be secure, easy to use or hard to detect. But seldom all three. In the book we read how ‘watchers’ who did surveillance on London streets used radio communications on a specific frequency, a frequency known to Soviet intelligence. Although individual watchers only listened & never responded, activity on this known radio frequency indicated to the Russian embassy that operations were afoot.

Wright & coworkers were eventually able to turn this around and detect the Russian radio receivers. They went so far as to use airplanes with suitable equipment to locate Russian receivers (even when they were not transmitting).

The book’s many details are very valuable to understand many near universal intelligence dilemmas. Some of the stories sound nearly insane, like how agencies treat suspicions of spies among their own ranks, or how they vet (‘screen’) government workers, but often not themselves nearly as well.

In terms of reliability, one advantage of 1985 books is that we can compare notes with more recent literature. Nearly everything in the book appears to be coherent with the rest of the works mentioned on this page.

Of specific note are his mentions of Agent Sonya which match the stories detailed in Ben Macintyre’s book, published over 30 years later. Similarly his then groundbreaking description of Project Venona has held up very well.

And finally - the jury is still somewhat out on if Roger Hollis was a spy. An authorized history of MI5 says he wasn’t, a review of that history says it was woefully incomplete. Much is made of Russian sources saying Hollis wasn’t working for them, and I don’t know what to make of that.

All in all I recommend this book highly (if you can’t find a copy, try this link). But as with all books on this page, do read carefully.

The Spy and the Traitor: The Greatest Espionage Story of the Cold War

Another Ben Macintyre classic.

John le Carré called this “The best true spy story I have ever read”. I don’t know if this is true, but it is an astounding yarn.

Oleg Gordievsky delivered top notch intelligence to MI6 from 1974 to 1985. His identity was kept so secret it was not even disclosed to the CIA. He died 21st of March 2025.

Macintyre spoke at length with Gordievsky, who then lived in London, and was also able to interview every MI6 officer mentioned in the book. There are volumes of footnotes and references.

I just browsed the book again and found it very hard to put down. I recommend you start reading it at your earliest convenience.

Meanwhile, I can also recommend all other Ben Macintyre books, especially Agent Zigzag, Doublecross and A Spy Among Friends.

The Spy in Moscow Station: A Counterspy’s Hunt for a Deadly Cold War Threat

Amazon. By Eric Haseltine, a former NSA director of research.

This book describes Russian efforts to spy on the US embassy on Moscow in the late 1970s and early 1980s. It is a fun read, and it partially overlaps with & corroborates “The Billion Dollar Spy”.

In addition, the Russian spying efforts described dovetail with stories told in “Tower of Secrets”, where elaborate countermeasures are described to prevent just the kind of eavesdropping described in “The Spy in Moscow Station”.

Unlike some of the other books, this one is heavy on technical detail and agency infighting. It is also a nice score settling exercise on behalf of the NSA, which had to fight for six years to get the US state department and CIA to acknowledge there was a massive technical leak in the Moscow embassy.

The book introduces the concept of the “who hates whom”-chart within the intelligence community, and how hard it is to cooperate – with your own friends.

It also expounds on how agency doctrines can lead management to declare absurd things in hearings, like how it actually is safer to employ Russians in the Moscow embassy instead of Americans, since the Americans might be bribed to spy on them.

I highly recommend reading this book and especially the afterword, which correctly notes there is a lot of “cyber” in the air these days, almost to the exclusion of any other technical means of surveillance.

John le Carré

Ahh where to start. Le Carré’s influence can’t be overstated. Comparable to how Mario Puzo’s Godfather trilogy eventually shaped mafia behaviour, Le Carré’s books have changed the very language of spying. Which is all the more odd since his books aren’t that factual, and don’t claim to be.

Altough Le Carré spent time working for the UK’s intelligence and security agencies, I prefer to think of him as a very gifted writer who simply made good use of his own backstory.

Through his literary works he shines a bright light on human frailty, loyalty and betrayal, all of which are still themes of modern intelligence and security work (even if you might not think so at first).

Some of his works are more literary than others, so you may not find all his books to be to your liking. I’m currently wading through The Little Drummer Girl which spends what feels like 100s of pages on character development. Enjoying it immensely though.

Another book The Russia House moves along much swifter, making valuable points about the reticence of the military/industrial/intelligence complex to report that things might actually not be as bad as we thought.

Even faster moving is the 2019 novel Agent Running in the Field, which makes strident points about the lamentable state of the current political climate, “Trumpism” and Brexit, and how these views pervade the intelligence world.

The Spy Who Came in from the Cold is a complex work that expounds on the conflict between spying methods and western democratic values. Le Carré revisited this 1963 novel in A Legacy of Spies in 2017.

Although most of his books were fictional, John le Carré’s work remains tremendously useful for understanding the relation between agencies, their governments, politicians, informers and agents.

Some outlier books

These books don’t quite fit the theme above, but they do provide valuable backstory to a lot of spy lore.

The Company: A Novel of the CIA

This massive piece of work (Robert Littell) mixes fiction and non-fiction and covers almost 50 years of CIA history. Many characters mentioned elsewhere on this page also feature in this book, and they are brought together in a beast of a story. There are also strong allusions and references to other books reviewed here.

Many of the events in this novel actually happened, and even the ones that perhaps didn’t are plausible. While this novel does not bring out the authentic details that characterize a lot of the books on this page, this work shines in providing an arc that goes from the last days of the Second World War straight to the appearance of Vladimir Putin.

Of particular note to me was the extent of how the predecessor of the CIA (the OSS) was shaped by the experiences in the war, and how this must long have remained a frame of reference for the company. Also, in a striking scene, we learn just how odd it was to work with all kinds of former Nazis headed by Gehlen to fight the Russians.

I can highly recommend this work as it ties a lot of the other books on this page together in one large riveting story.

Seizing the Enigma: The Race to Break the German U-Boat Codes, 1939–1943

Amazon. By David Kahn.

A bit of an outlier - I have not included a lot of the vast World War 2 literature since it sheds comparatively little light on modern espionage and intelligence.

“Seizing the Enigma” is an exception since it forms a wonderful introduction to just how hard it is to communicate securely, and just how hard signal intelligence departments & agencies will work to break codes.

As far as I can tell, when this book was published in 1991, it represented the only public document on modern cryptographical doctrines - even though it described World War 2 practices, which turn out to have been very advanced.

Besides being factually useful it is also a ripping read on how various German codes were broken.

Cryptonomicon

Wikipedia. By Neal Stephenson.

This is a complete work of fiction, set partially during the second World War, partially during the 1990 internet boom era. Even though it is fiction, it covers a lot of Bletchley Park spy lore, with ample Alan Turing references. The first 100 pages are a bit of a slog but the rest is pure gold.

There is a lot of cryptography in this book, but there are also large themes on how secret agencies are dancing in the dark about each other’s abilities, and how to pick up clues by observing what the enemy is (not) doing.

The scene where Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto’s plane is shot down because the allies cracked the Japanese codes is a work of art.

Victor in the Rubble

Amazon. By former CIA officer Alex Finley.

A hilarious & satirical view of the fictional ‘CYA’ intelligence agency. Laugh out loud funny, but along the way makes critical points about the nature of modern intelligence work. Hasn’t it gotten a bit out of hand maybe?

As she writes in the acknowledgments section of the book “Writing this book began as catharsis. For years while most people watched an official narrative of the ‘war on terror’ unfolding in all its inglorious grimness across the global stage, I sat in my little cubicle and witnessed absurdity. […] I will let the reader speculate on where things lie on the truth spectrum, but I will say Mark Twain was right: Truth is, indeed, stranger than fiction”.

From personal experience, I can confirm many of the absurdities reported in the book. But do also read it for the laugh out loud parts!

Some mini reviews & articles

- The Happy Traitor by Simon Kuper (also available in Dutch). “A ‘humane and informative’ (according to John Le Carré) biography of George Blake, the most notorious double agent in British history”. George Blake had his roots in the Dutch Second World War resistance. The book offers a fascinating view on a non-traditional defector. Kuper gives us ’the last word’ on Blake, having interviewed him in Moscow in 2012, with the benefit of the large existing literature on this Dutch-English spy. The book paints a very interesting picture of Blake, and almost as an aside addresses many big questions in espionage: why do we do it, is the data useful, is it even used and what is the human cost?

- Operation Easy Chair by Maurits Martijn. An in depth investigation of a Dutch company that somehow ended up building microwave operated microphones for the CIA. Gives a taste of how things in the world of intelligence often don’t appear to make sense - why would the CIA need Dutch assistance? Sometimes the answer is “four dimensional chess”, sometimes it is constraints imposed by politicians.

Some other books

These are interesting books that I have partially read, but have not yet formed an opinion on. Feedback is very welcome.

- The Secret Sentry: The Untold History of the National Security Agency, covering developments from 1945 until quite recently.

- The Main Enemy: The Inside Story of the CIA’s Final Showdown with the KGB

- Near and Distant Neighbors: A New History of Soviet Intelligence

- Villa Maarheeze (Dutch), on the obscure former Dutch Foreign Intelligence Service IDB

- Spionkoppen (Dutch), on the past 11 heads of Dutch General Intelligence & Security Service AIVD

Well informed readers have meanwhile recommended the following books, which I have not yet had a chance to look at:

- Code Warriors: NSA’s Codebreakers and the Secret Intelligence War Against the Soviet Union, by Stephen Budiansky

- Dark Mirror, by Barton Gellman, on his many interactions with Edward Snowden

- Russians Among Us by Gordon Corera on Russia’s illegals program. Corera has also written several other books, including on MI6, nuclear proliferation (including Dutch-linked Abdul Q. Khan) and espionage in cyberspace

- Three Minutes to Doomsday: An Agent, a Traitor, and the Worst Espionage Breach in U.S. History, by Joe Navarro. A gripping counterintelligence investigation.

- Samen met de CIA (Dutch), by Cees Wiebes

- Vijandbeelden (Dutch), by Constant Hijzen

- At Risk, by former MI5 director general Stella Rimington. According to reviewers, “One senses the author’s intimate knowledge of this world here”. Part of a series.

Some final links

- Do not read any Tom Clancy to learn about intelligence agencies. Do however read this CIA-authored spoof of “The Hunt for Red October”. “I was specifically told that “you aren’t truly initiated into CIA until you think that ‘The Hunt for Red October: The Untold Story’ is funny.”

- NSA review of EUROCRYPT ‘92, PDF page 15 and onwards.