But how to get to that European cloud?

The very short version: It has now become clear that European governments can no longer rely on American clouds, and that we lack good and comprehensive alternatives. Market forces have failed to deliver a truly European cloud, and businesses won’t naturally buy as yet unproven cloud services, even when adorned with a beautiful European 🇪🇺 flag, so for now nothing will happen.

This article is part of a series of posts on (European) cloud challenges.

This means it’s time for industrial policy, which requires politics to be proficient in “industry.” Such proficiency is the only way to develop policies and plans that don’t go off the rails (which, unfortunately, can happen in many ways).

With a coherent strategy (see below for a suggestion), governments and industry can rapidly improve the cloud situation, allowing Europe to once more manage its own services without American prying eyes and without fearing the consequences of sanctions & transatlantic disputes.

That concludes the short version.

This page originates from a productive discussion on the BNR podcast De Technoloog, along with conversations with members of parliaments, civil servants, and entrepreneurs. It is also written with knowledge of this new letter about the EuroStack to the European Commission (LinkedIn post).

In the article “The (European) cloud ladder: from virtual server to MS 365”, I outline what is and isn’t available in Europe. There are already plenty of components, at a sufficient scale, to build upon. We can start improving parts of the cloud almost immediately, and eventually develop something with capabilities comparable to AWS, Google, and Microsoft Azure. But it will take a decade of hard work.

Europe and the EU have overcome massive challenges before.

For example, at one point, it was unthinkable that we could operate without the American GPS system. Today, every phone and every smartwatch also uses the EU Galileo satellite system, and Galileo is now the best satellite navigation system in the world. It only cost €15 billion!

Similarly, we once had many separate aerospace and defense companies, but after more than 10 years of mergers and restructuring, we got Airbus, which now makes the best large aircraft in the world. That was once unimaginable too.

By now, almost everyone agrees that we need to do something similar for “the cloud”—and take it even further: we also need European solutions for workplaces, word processors, and other office applications.

Massive sums of money are already being discussed—tens to hundreds of billions of euros—so funding will be available one way or another. If we can spend €800 billion on defense, we can do something for the cloud as well.

It’s also worth noting that Europe is full of technical talent, including the people who built much of the technology powering the major American cloud providers. The only issue? Much of that European talent is employed by American companies or working on open-source projects as a hobby in their attic (🙋♂️).

The question is: how do we combine talent and funding to create a better European cloud? Because we need to do more than just declare that Europe should invest in things.

Governments & Contracts

Roughly speaking, governments produce almost nothing themselves—except for policy, and even that is sometimes outsourced (to lobbyists or consultants).

However, governments do commission vast amounts of roads, bridges, and other infrastructure projects. That’s already complex enough, but at least you have a fairly clear idea of what you want in advance, and there’s an industry that routinely delivers these kinds of projects.

Things get trickier with more complex projects full of surprises, such as the renovation of Dutch parliamentary estate het Binnenhof. Sometimes, these projects spiral completely out of control. The most recent examples come from Germany, such as Berlin’s airport or the new Stuttgart train station.

But all of this pales in comparison to the challenge of launching a new IT project. And this isn’t just a government problem—even if you know exactly what you want, the IT world has more or less given up. “We can tell you what it will cost, when it will be finished, or what it will do. Pick at most two.” Or, honestly, just one.

In practice, it often turns out that the project’s goals, purpose, or target audience are unclear, making everything even harder. In the Netherlands, the Advisory Board for IT Assessment is doing excellent work with research and recommendations—but their findings are almost always painful to read.

It would be fantastic if governments took a more hands-on approach to creating successful IT solutions again, but there’s a long way to go before they can regain the capability to do things in-house. Still, I’d be excited about that prospect.

Ordering a Cloud

The market hasn’t provided a solution, so governments must now figure out how to foster the creation of a functional cloud. As mentioned earlier, this problem can actually be broken down into smaller, manageable pieces—we don’t need to build an entire Airbus or IKEA right away.

For politicians and decision-makers, it’s tempting to see this as another Galileo: allocate €15 billion, and a consortium will build a cloud. The big political decision, then, is simply to fund it, which is doable in politics (for example, for “AI factories”).

But this approach won’t work because, unlike Galileo, there is no industry ready to deliver such a project (even though some companies like to pretend there is). And crucially, Galileo had a crystal-clear objective: 1) Deliver exactly what GPS offers. 2) Build on top of that with further innovation.

What we need across different layers of the cloud is largely not off the shelf. It’s not just about servers and hardware—it requires development.

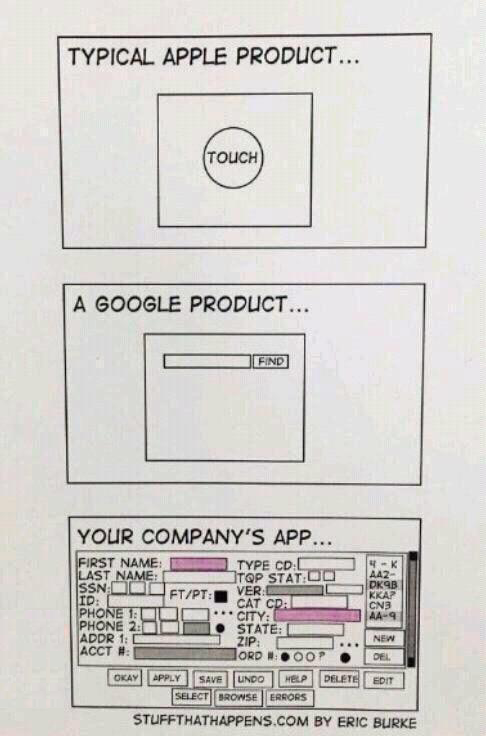

What you get if you ask an enterprise IT company to build you something. Source: Eric Burke via spyvee.com

Learning from Past Experiences

There are some lessons to be learned here. To develop Galileo, the EU was able to lean heavily on the European Space Agency (ESA). ESA has extensive experience in commissioning satellites and designing and testing massive projects. It costs a pretty penny, but the results are solid. Take, for example, the Ariane 6 rocket, which performed well in its first two launches instead of exploding 17 times before getting it right (though that approach can also work—it does accelerate innovation).

However, we don’t have a “Cloud ESA,” though we sometimes hope that an organization like TNO could fill that role.

A persistent misconception is that you need to put tens of billions on the table upfront before you can “build a cloud.” That’s not true, you can start with much less and still create credible services. But an even bigger misconception: just because you spend billions doesn’t mean you’ll actually end up with something useful! In many cases, the money might just get burned up in endless meetings.

What About Subsidies?

Another option is to make funding available through subsidies, which can work well for certain objectives. For example, subsidies have been highly effective in promoting home insulation and have helped the Netherlands become the world leader in solar panels per capita. Due to a policy oversight, the Netherlands has now installed the equivalent of nearly 50 nuclear power plants worth of solar panels. This is a massive impact.

Europe has extensive experience in distributing R&D subsidies. The massive Horizon Europe program allocates around €15 billion per year for this purpose. I’ve personally been a Horizon Europe reviewer for the European Commission, and I hate to say it, but this system is terrible for real innovation. You need to submit a highly detailed plan outlining exactly what you’re going to do, and deviating from that plan is an absolute bureaucratic nightmare. No true innovative entrepreneur wants to deal with this.

The ones who do want to deal with it are slow-moving consortia, staffed with entire floors of people who love defining and checking “work packages” full of “milestones.” These milestones get met, everyone is happy, the money is spent, and you end up with something. But chances are, it won’t actually solve the problem you set out to address. Some of the IPCEI-CIS initiatives in the Netherlands may also fall into this trap—though I sincerely hope they succeed.

And this brings us to a crucial point: if we want to build an innovative and modern cloud here, it cannot happen without enthusiastic programmers, developers, and entrepreneurs. There is no other way. And rigid, bureaucratic subsidies will never generate that enthusiasm.

My former company, PowerDNS, went through a failed subsidy program in the early 2000s. It was a traumatic experience—being treated as a potential fraudster while trying to do your best. We barely made it out unscathed. It’s something you never forget.

Smart Procurement?

One major problem is that businesses and governments are very clear about not wanting to deal with new things. The European Commission, for example, is currently in a ridiculous legal battle against its own privacy watchdog just to keep using Microsoft 365. Or take the Dutch Ministry of the Interior, which shares the IP addresses of all its secret service job applicants with Google because it’s supposedly tens of thousands of euros per year cheaper than European alternatives. These are strong signals.

Now, every entrepreneur knows that you have to develop products that customers don’t yet realize they need. But you should at least be able to reasonably predict that they will need them in the future and they need to be open to trying something new.

And here’s a direct quote from the Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs’ policy (as stated by the State Secretary of the Interior):

“There are no possibilities to award government contracts exclusively to European and/or Dutch companies. This is legally impossible due to obligations arising from the (WTO) Government Procurement Agreement and our trade agreements.”

Well, that’s it then. If this is the stance, then European industry is given zero pathway to success. “We’ll only buy from you once your products are the absolute best, according to our procurement standards.” But during the early years of development, your products will inevitably have rough edges and won’t yet do everything. And they will certainly be more expensive, because we don’t allow European companies to get away with selling our data—but somehow, American companies can.

I actually doubt whether the minister is correct about this “Government Procurement Agreement.” It would have to be the United States that sues us at the WTO, and the U.S. itself no longer believes in the WTO. In fact, almost no one does anymore.

Despite all this, smart procurement could play a huge role. Governments are the largest purchasers of IT services across Europe. If done wisely, this could effectively signal to the market, entrepreneurs, and developers that their products are in demand. And the scale of government IT is so vast that there are plenty of projects where a (small) risk could be taken—projects that aren’t mission-critical 24/7 and aren’t overly complex.

It’s also possible to procure solutions for specific gaps in European digital services through targeted tenders, such as this innovation challenge:

- Email is dominated globally by “free” services (Gmail, Outlook.com). These services are ultimately paid for by selling us. While paid email services exist in Europe, we now know that competing with “free” is nearly impossible. So, build a “Eumail” platform that provides free email to everyone. This probably should not need to be government-run, but the platform could be commissioned and funded to deliver top-tier services. Doing this properly might cost €100 million per year, but imagine the impact!

- A European anti-DDoS shield. This market is currently dominated by a small number of U.S. companies, which means they have visibility into our internet traffic. Some of these companies (like Cloudflare) even offer free services, leading to the same issue as above. We already have a great non-profit initiative, but it could be expanded significantly.

- European governments currently broadcast press conferences via YouTube. It’s high time for a reliable, user-friendly “Eutube,” so that crucial public information doesn’t get sandwiched between conspiracy theorists. This is becoming an existential issue.

- All major web browsers are American, and largely controlled by Google. Firefox has a much bigger market share than most people realize (especially now that Chrome and Edge are blocking ad blockers). But Firefox, despite being open source, is mostly funded by Google! A great move would be to take over that funding and finance “fEUerfox” for 10 years, ensuring a browsing experience that doesn’t route everything through the U.S.

- The open-source ecosystem now largely depends on Microsoft GitHub, which is heavily AI-focused. And, once again, free. There is a European alternative, but since it doesn’t monetize user data, it has limited resources and lacks many features. This could be funded for a trivial amount of money.

- Local media now rely overwhelmingly on Facebook (!!) for publishing and engaging with readers. Since all politics is local, it’s crucial that local journalism isn’t controlled by Meta. There are existing initiatives, but no viable business model. Fixing this would cost very little, yet the benefits would be enormous.

- Many national media organizations are completely dependent on Google Docs. Google Docs, on its own, isn’t as complex as the full MS-365 suite. There are already open-source alternatives that are almost good enough. A robust, public, alternative could allow media organizations to operate independently of U.S. surveillance.

With a series of well-structured procurement contracts spread across Europe, we could massively accelerate the development of better European cloud services. Especially if these initiatives build on one another. But, as mentioned, it takes courage to prevent “smart procurement” from simply being won by Amazon, Google, and Microsoft.

As a suggestion for the minister: Procurement rules state that you cannot explicitly exclude any company (except on national security grounds). However, you can include criteria in your selection process. For example, requiring that vendors only fall under European surveillance laws. That’s a completely reasonable demand — and no U.S. (or U.S.-linked) company could ever comply.

With targeted contracts, the industry could, for example, collectively improve or further develop open-source products that are essential for large-scale cloud usage. After all, everyone needs the same core functionality. A group like Germany’s Sovereign Tech Agency demonstrates how this can be done. The Dutch foundation NLnet is also making great strides in this area.

The beauty of this kind of smart procurement is that it empowers the market to build great things, without requiring a rigid blueprint for how to do it. You don’t need a “Cloud ESA” for this. But you can strongly encourage valuable developments. And, with a billion euros, you could go a very long way.

But Industrial Policy Isn’t Easy

At the same time, this is industrial policy. For the past 50 years, that’s been a dirty word. But when the free market doesn’t deliver what you need, and private companies won’t solve it for you, then you have to do something.

If you want to engage in industrial policy, two things are critical:

- You need a deep understanding of politics.

- You need a deep understanding of industry.

And that is going to be a massive challenge.

At the highest levels of European governments, there are almost no (technical) experts. Worse still, it seems that these leadership circles actively dislike technology and would rather discuss other topics.

But this knowledge is essential. While it’s not a good idea to try to “pick winners”, recognizing quality (or the lack thereof) is absolutely crucial.

The European Cloud Industry: Why Hasn’t It Taken Off?

The European cloud industry has struggled to take off, partly because existing players lacked the will or vision to compete effectively (among many other reasons). It’s tempting to place too much value on the ideas of the relatively most successful existing players, but it’s essential to understand why these companies haven’t broken through earlier.

Not to be taken too seriously, but this is a roughly to-scale comparison of U.S. cloud providers versus European ones. Take a close look at the bottom right, near the “e” in Google.

Additionally, there are many organizations in the market that convincingly claim to be the future. Unfortunately, heavy investment in PR often creates a better initial impression than heavy investment in technology. By now, I have a solid list of timewasters for anyone wondering whether an initiative is legitimate or just hot air (feel free to email me).

I initially didn’t want to mention this, but several proofreaders spontaneously reported bad experiences, which I have also had myself. If you are approached by the company Arqiver or the “EU FED Cloud,” be aware that they did not leave a good impression on me at all.

There are also false prophets—we all want quick solutions, and sometimes we get (too) excited about people who promise them. For example, in Germany, some claim they have “made Microsoft’s cloud European” through SAP. However, this turns out to be not quite the case. If the U.S. refuses to cooperate, they (by their own admission) would be down within a few months.

Amazon also claims they are going to do something similar, but they’ve been saying that for years, and they conveniently avoid addressing what happens in case of a conflict with the U.S.. We should also be very cautious about believing in “saviors” like the Lidl Cloud, or even Cloud Kootwijk. Seeing is believing.

Another risk factor is the confusion between open, standardized, and autonomous. Many hardcore technologists firmly believe that federated, open, standardized systems are the solution. And to some extent, they are right. But having such technologies available is only a necessary condition—it’s not a solution in itself. Just because the technical prerequisites are met doesn’t mean a market will automatically emerge.

Having standards for interchangeable services is a great thing because it enables choice. We don’t need a single EU Cloud Airbus! At the same time, a profitable business model must emerge—we can’t try to create a market where there’s no money to be made, because that market simply won’t happen.

Finally, there’s always the temptation to rely on large, established defense and IT companies that claim that this time, they can deliver something fresh and innovative. And sure, maybe they can. But these companies are fundamentally not designed for real innovation or rapid development. Moreover, we must question whether they even want to—virtually all major existing players are completely entangled with U.S. big tech. That’s a problem in itself. Even if we develop new software in Europe, we still need large companies that are willing to manage and integrate it.

Summarizing, industrial policy is not easy. It will only succeed if governments independently develop and retain deep knowledge of industry, allowing them to determine what works, what doesn’t, and which direction will lead to a stronger European cloud industry.

Open Source

Europe may not excel at commercialization, but we are good at collaboration (more on this later). Nearly every initiative aimed at “doing cloud better in Europe” revolves around open source, because that’s where we have a strong foundation. However, this won’t happen automatically.

The initiatives mentioned earlier—such as “Eumail” and “Eutube”—will deliver the best results if they are built on shared code, libraries, and infrastructure. That way, every euro invested benefits multiple projects simultaneously.

At the same time, open source is not a solution in itself. Successful IT services depend on robust support, training, integration, and reliable operations.

We also need to carefully consider how companies will actually make money. Our lovely European services should not be overshadowed by competitors who offer the same software but undercut us in pricing by selling user data.

As mentioned before, industrial policy is anything but simple—even when open source is part of the equation.

Other Options

To shake things up, we need to do things differently. As mentioned, Europe has a wealth of talent. The “American way” of creating successful new companies through risky startups is one approach. I’ve previously written about why that approach doesn’t work well here. We can’t just play Silicon Valley in Europe. And even in the U.S., that model mostly produces products that spy on users, flood everything with ads, and push unwanted AI. So, it’s not exactly the best model either. They can’t even seem to establish a basic bank that allows people to transfer money (!!) without requiring apps full of trackers for some reason.

So, what can we do? Earlier, I mentioned that traditional subsidies don’t drive innovation. In Germany, they’ve addressed this by creating SPRIND, and I’m very enthusiastic about it (partly because they sometimes hire me as a reviewer, and also because the director was formerly the head of my old company, PowerDNS).

“The Federal Agency for Breakthrough Innovation SPRIND invests in new groundbreaking technologies and topics that have the potential to fundamentally improve our lives.”

Applying for support for your project is done via a very simple form. Then, experts review the project and actively work with you to improve your proposal. After that, you give a presentation, and if all goes well, you receive funding. The goal is for the entire process to take 12 weeks. There have already been cases where scientists burst into tears upon simply being told that their work was good.

This almost sounds too good to be true, but in Germany, a country not exactly known for its dynamic government or flexible procedures, it’s working like a charm.

And unlike Silicon Valley, what works in Germany can be replicated elsewhere in Europe. We’re in a very similar situation. You could almost directly copy this and create a Sprin-NL.

A Coherent Strategy

This is just a blog post, but from the above, a coherent strategy emerges:

- Clearly communicate that European privacy standards will eventually be enforced, making the use of U.S. cloud services increasingly uncertain—especially for sensitive personal data (Article 9 GDPR).

- Governments should actively signal a genuine willingness to do business within Europe. Be prepared to take a creative approach to procurement and use WTO GPA Article III exceptions for privacy and security (if not now, then when?). Also, recognize that the U.S. itself no longer believes in the WTO—so let’s not use WTO rules just to do them a favor!

- Hire people within government agencies who have deep industry knowledge. That’s the only way to develop effective industrial policies. Also, start doing more projects in-house without relying on consultants or external procurement—nothing teaches you more than hands-on experience.

- Work with experts to identify key cloud functionalities that do not yet have strong open-source implementations, then commission their development or improve existing software. Follow these principles to ensure the results are well-documented, secure, and easy to use. Germany’s Sovereign Tech Agency demonstrates how this can be done effectively.

- At the EU level, commission the development of key services like “Eumail,” “Eutube,” and a European alternative to Google Docs. Encourage the use of software from point 4 and support providers that embrace these solutions.

- Follow an “Airbus model”: use procurement policies to encourage the consolidation of the European industry—something made easier if the software from point 4 sees widespread adoption.

- Take legal action based on point 1 to show that enforcement is serious.

- Establish Sprin-NL or actively participate in a potential Sprin-EU.

- In the event of a trade war, consider imposing import tariffs on U.S. cloud services.

Some of these steps (such as points 3, 4, and 8) are good ideas regardless. Others only make sense as part of a broader, coherent package. For example, it wouldn’t make much sense to pursue legal action (point 7) to force companies to switch to alternative providers if those providers don’t yet exist.

NOTE! This coherent strategy has been expanded and improved and now has its own article: A coherent European/non-US cloud strategy: building railroads for the cloud economy

Conclusion

There are multiple ways to make progress. Governments can take a more hands-on approach, using smarter procurement strategies for standard IT needs as well as special initiatives like Eumail and Eutube. They can credibly signal their intention to start buying European open-source solutions again (and stop fighting legal battles that prevent them from doing so). Better-designed subsidies could help, or something like a Sprin-NL could be established.

In all likelihood, we need to do all of these things simultaneously. The urgency is high enough that we must bet on multiple strategies at once.

The common thread in all of this is that governments need much deeper technological expertise and must integrate that knowledge into policy-making. Because only with a strong understanding of industry can you implement effective industrial policy.

And if we do this well, we might just be able to create a European Airbus for our industry, building something meaningful by working together to elevate essential software to the next level or helping to consolidate key players.

This way, we can regain control and stand on our own feet again.

Good luck!

This article has a followup: A coherent European/non-US cloud strategy: building railroads for the cloud economy