Demystifying European Digital Sovereignty

This article is part of a series on (European) innovation and capabilities.

Recently I participated in a very useful panel that aimed to demystify European digital sovereignty. Even though we spoke for more than an hour (video), we obviously were not able to fix all of Europe’s sovereignty problems!

The event was organized by Scaleway (previously Online SAS or Online.net), a 100% subsidiary of what I think is Europe’s most innovative telecommunications company, Iliad.

Various big people were invited, like:

- Yann Lechelle, CEO of Scaleway

- Erja Turunen, VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland, GAIA-X board member

- Jeff Bullwinkel, Assistant General Counsel and Director of Legal and Corporate Affairs for Asia Pacific & Japan for Microsoft

- Peter Ganten, entrepreneur & CEO of Univention, chairman of the German Open source Business Alliance

- Chris O’ Brien, European correspondent of Forbes

I think I was part of the panel because I’ve previously written some very strident words on Europe’s Software Problem, and on the problem of near universal telco outsourcing to places outside of Europe.

Now, I don’t want to do a full recap of the event - we spoke for quite some time, and touched on a lot of themes. But I do want to highlight some important things.

What are we talking about?

Sovereignty and autonomy are lofty words, but we can also take a very practical approach. Here in Europe we get almost all our digital (communication) services through foreign platforms. This leads to the first concrete question: what are those people abroad doing with all our data? There are significant reasons to worry about this. The US CLOUD Act, the scant legal protection US and Chinese law afford to foreign data, and the way major platforms have been massaging the GDPR to their advantage are not reassuring.

The second question is, might we get into problems later if we utterly depend on two other continents to get anything done? This is the case right now, to be clear.

These are not small questions, and these are things we should be worried about.

Europe’s dependence

To address the situation, we can look at the problem from several angles. Through regulation we can attempt to make sure that the companies around the world that process our data do so in accordance to our rules and regulations. This requires extraterritorial legislation, something that has typically been hard to enforce.

We would also like to see a lot more of our digital services actually come from our own territory, where our values are much better understood and our laws and regulations are more easily enforced.

Repatriating digital services requires that we have European companies offering those services.

Companies are created by entrepreneurs (in general), and this then turns to the question if it is attractive right now to launch such companies in Europe.

The world, including Europe, has come to rely on excellent services that are generally offered at very low to zero monetary cost. There are various reasons for the low cost, but there is not a lot we can do about it. We might perhaps compare this to WTO “anti-dumping” regulation, but I don’t think it would get us very far.

As Scaleway summarised what I said: “The situation is getting worse. In Europe, we’ve said we’ll outlaw selling of data (via GDPR), but we let companies like Facebook get away with it. So we’ve not found a way to approve a new, European business model. We’ve closed a door, but not opened a new one”.

But this does not explain everything.

The conversation

What struck me during the event was the disconnect in language. On one hand we have discussions on digital autonomy and “data flows”. We also talk about the need to standardise cloud services, which would allow interoperability and a more level playing field. Other cloud providers could then conceivably “slot in” to platforms as part of multi-cloud solutions, all to better meet the needs of users

But on the other hand, in the market, nobody is using words like these. Customers need reliable and affordable services. And they are currently getting them from Amazon, Microsoft, Google and others. These companies are doing excellent work.

In addition, experience from the field shows that the vast majority of players will not be able to make multi-cloud solutions work. And in fact, cloud providers are well incentivised to make sure that they don’t work well! Although it has to be noted that some players, like Scaleway are trying to make this easier.

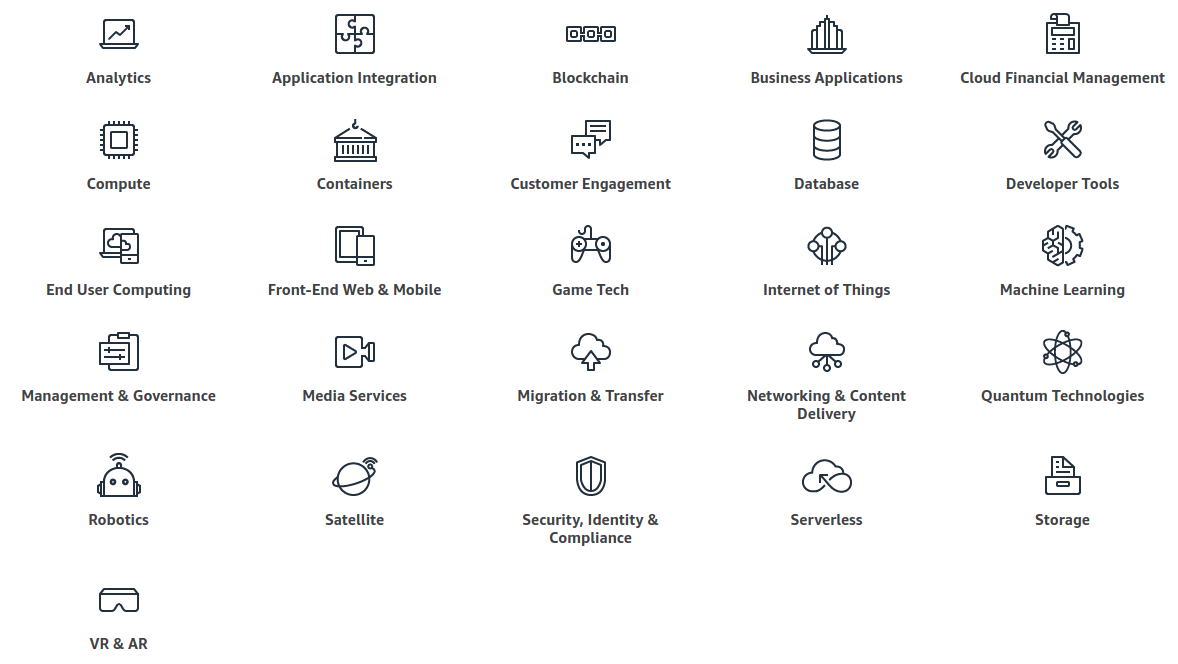

A summary of Amazon services

From a distance, it is easy to talk about “cloud providers” as providers of computing and data services. Superficially this is true of course, but I wonder how many policy makers have actually logged in to an AWS console and truly experienced the wealth of products being offered there. As an example, you don’t just rent a server on AWS, you rent a fully backupped globally distributed database, and a lot of the value is in that service, and not in the hardware.

The more specific a service, the less likely it is that it will be possible to migrate it between multiple cloud operators. And there are many such services.

In short, for now the market is rather happy with what it is getting. Europe might show up with a cloud that has theoretical advantages, and that is somehow better because it is European. But in reality, who owns the legal entity that operates the servers is almost meaningless for users.

Talking about data flows is well and good, but it does not resonate in any way with decision makers in the market. They’d buy European services if they were just as good and perhaps slightly cheaper. But not because they are European.

We can also think a bit about why there is no European AWS (or Azure or Google Cloud Platform). This has little to do with regulation.

Industrial policy

Industrial policy has not been a much appreciated thing over the past few decades. But we can’t shy away from it if we actually want to influence industry.

Around the year 2000, Europe found itself relying utterly on the US operated Global Positioning System. At the time, the US Air Force deliberately degraded the precision of GPS for civilian users. It was also clear that GPS service might be withheld for strategic or military reasons.

The European space and defense industry was of course very interested in rectifying this situation, as was the EU itself. The US meanwhile was exceptionally unhappy that Europe wanted to build its own satellite navigation network, they were quite fond of being able to determine where global positioning was available, and how precise it would be.

Through a very complicated, and in many ways admirable, process, eventually in 2016 the European Galileo project went live (with some caveats). Today, global positioning is being supplied by American, Chinese, European and Russian satellites. Every phone sold today is able to benefit from all four systems - simultaneously.

In order to make this work, eventually the US and Europe (and even China) cooperated and made sure their positioning systems used very similar mathematics and principles, enabling the development of chipsets that support all systems simultaneously.

Crucially, the EU went round with a big bag of money and concrete help to make sure that chipsets would actually support Galileo. This has been a massive success.

As it stands today, investing in Galileo has delivered some actual European sovereignty and it has also supported and improved our space industry.

GAIA-X: Galileo in the Cloud?

Europe is attempting to foster the generation of a European cloud infrastructure, and this project is called GAIA-X.

From the Wikipedia:

“GAIA-X is a project for the development of an efficient and competitive, secure and trustworthy federation of data infrastructure and service providers for Europe, which is supported by representatives of business, science and administration from Germany and France, together with other European partners.

The objective is to design the next generation of a federated European data infrastructure. Common requirements for a European data infrastructure will be specified and a reference implementation developed.”

This is remarkably like the Galileo project, which was an application of traditional EU policy: We want something, we define it pretty well, standardise it, and finally start the procurement procedure. And many billions and a decade later, it goes live. It worked.

Note that GAIA-X only intends to set the standards, and not actually finance a European production cloud.

If Europe wants to create digital sovereignty in the cloud, it can’t rely on this traditional process. The clock speed of the cloud is vastly different - there are no decade long roadmaps. In addition, the customers are not major chipset manufacturers you can get on board by working with them.

Everyone is the customer of cloud services.

In the history of the EU, or perhaps in the history of governments in general, never has a country been able to launch a company that could outcompete actual market participants. And it is not going to happen now.

I worry that as long as we are talking about data flows and cloud interoperability standards, we aren’t even making a start of creating a compelling European offering.

What to do?

We might do well to take a step back: why is there no European Gmail or Office365? Why haven’t we generated an Amazon Web Services (AWS)?

GDPR is often mentioned in this context, but that does not explain why there is no AWS.

Some other reasons were also raised during the Scaleway panel.

Valuing technical talent

One of the sticking points is that European companies do not value technical talent. It is hard to compare US and European salaries directly, but from a cursory glance it is clear that Silicon Valley pays extravagantly more, even outside of California.

Another perhaps more useful way to look at it is the relative European appreciation of marketing, legal and financial talent compared to software people. In almost every European corporation, software talent is valued far far less than those other departments.

The legal department protects your innovation, and it appears we value it highly. The engineering people actually perform the innovation, but somehow they are way down the compensation ladder. The net effect is that a lot of software talent ends up leaking to such terrors as the blockchain and high frequency trading.

Such things can not be changed by European policy. Instead, the salary choices we see may reflect an actual lack of desire to compete on technology. As a case in point, technology is being outsourced more and more, and not seen as a core skill.

Being a launching customer

Another obvious thing is that it is hard to compete with very well established players. One thing that governments could do is “vote with their feet”. The effect of having some of the largest organizations in the world as your reference customer is huge. You can shorten your your sixty page sales presentation to a single slide featuring a German flag and put “Questions?” underneath, for example.

It is not widely known, but formally the US government is obligated to buy many things exclusively from American vendors. This legislation is full of loopholes, but as a vendor you do encounter it, and have to create paperwork before even being able to compete.

In Europe we typically do not work this way, and protectionism is rarely good. But if our governments prefer to pick tried and true solutions from other continents, it is hard to get anything new going. Yann Lechelle from Scaleway expands on this in “Towards a “European cloud decade”: let’s dare to aim for reciprocity at EU level!”

We may be too laid back

It may also be good to recognize that European entrepreneurs generally aren’t as ruthless as those from other countries. A lot of innovation comes from technical people that want to apply their skills to fun problems. If the conditions are right, such actual innovation happens nearly automatically out of an innate desire to invent cool new stuff.

It is rather easy to get people to think about such innovations under the shower. But these innate innovative feelings do not extend to whipping your company into a world dominating money making machine that extracts every bit of value out of its overworked staff.

If Europe wants to compete, we might need to recognize we need to excel at the things we are good at, and not try to outcompete the Facebooks and Googles of this world at their own turf.

Using our strengths

One area where we could excel is that very lack of competitive ruthlessness. For example, could you imagine having an open source Gmail competitor where the massive amount of European technical talent actually contributes new features? Or developing collaborative solutions for schools that do not send out needless volumes of metadata for “analysis”?

Or perhaps I could look at my own Galileo hobby - with our 90-strong network of volunteers, our Galmon.eu project has made a small but measurable difference to the operation of Europe’s navigation network. This is all based on open source and open cooperation.

There is no shortage of technical talent in Europe – much of it is even working for Google, Facebook, Amazon. There is no reason we can’t do great things, if only we find a way to do it.

Europe is very used to stimulating big economic things with funding. Although the situation with software and digital services in Europe might seem rather bad right now, as I noted elsewhere, even a 1 euro/year tax on Europeans would already be enough to power some very large initiatives. This could go a long way to enabling competition with “free” services - if only we could find a way to channel these funds into productive projects.

Summarising

The discussion on European digital sovereignty is alive and well, but I worry that the high level policy initiatives are disconnected from what operators actually want. Talk about data flows is good and well, but users are currently receiving very good cloud service from outside of Europe. They aren’t that worried about data flows.

To change this, we first need to make sure we have services here that are just as good or better. The fact that they come from Europe is nice, but not in itself a compelling sales argument.

Using regulation we’ve eliminated many software/services business models, but this has not stopped companies outside of Europe pushing their “pay with your data” wares here. We can try to stop this with legislation, but we should realise we closed down a business model for European companies without opening up new one.

To engender big changes, Europe needs to think about industrial policy to enhance autonomy, and take a good look at what worked in the past (Galileo, for example), but also realise that this problem is different, and that in the cloud, there are no decade long roadmaps.

Europe has many things going for it, like having a massive amount of technical talent living and working here – but often for American companies.

If we want to play a role, it is best to not try to out-California California, but to try to excel at things that we do have going for us, like a less ruthless and more collaborative business climate. With open and privacy sensitive solutions, we can play a role.

With modest funding, we could apply our local talents to at least start to make big changes.

This article is part of a series on (European) innovation and capabilities.